08 September 2023

China to build infrastructure in solar system? (Image: Adobe)

It’s now long been seen that SpaceX are the frontrunners in the commercialisation of space, through reusable launches, establishing their Starlink satellite mega-constellation and becoming the go-to ride-share service into space. The launch of Starship will also see them play a key role in the Artemis lunar landing program and establish a path towards interplanetary travel.

Elon Musk recently claimed that SpaceX has exceeded last years launch numbers and transported 80% of all payload mass to orbit so far this year. Furthermore, their September 4th Starlink launch saw them set a new record for annual launches (62), beating a record previously set in 2022. By 2024, Musk aims to deliver 90% of all mass to orbit and once Starship is online, he expects that number to rise to 99%.

These figures truly are a testament to the sheer innovation and speed at which SpaceX have moved, opening-up access to space for more and at a much lower cost. However, that dominance isn’t necessarily being received well by all. A piece from the New Yorker claims that some think the tycoon holds too much power and influence.

We’ve also previously noted that some nations and agencies, such as ESA, may not favour relying on a single supply chain and rather establish their own, sovereign launch capabilities. It may also present a problem should SpaceX become embroiled in any kind of geopolitical dispute, such as the use of Starlink in Ukraine, and become a target of warfare. So despite this dominance, there may still be the desire for nations to diversify and allow room for more commercial entities to expand their capabilities.

SpaceX dominates but nations want to open-up for more cooperation

While SpaceX might aim to dominate the launch market, there is ongoing evidence of a willingness to open-up space for cooperative projects. The UK Space Agency is ploughing ahead with its plans under their International Bilateral Fund investments, and will allow the agency to work with the US, Canada, Australia, Japan, India, Singapore, South Africa and more.

They have recently announced collaborations with Australian partners on projects such as lunar regolith sampling, Earth observation and in-orbit servicing. In addition to this, the UK has announced a partnership with the US relating to electric space propulsion, involving Pulsar Fusion (UK) and the University of Michigan.

China also look to commit to using their orbital space station (Tiangong) as vessel for international cooperation. A report released on August 28th from the Department of the Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) stated that this use of Tiangong could change perceptions of Chinese intentions in space, saying that “The People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA’s) intention to allow civilian astronauts and nonstate-owned enterprise (SOE) companies to participate in the Chinese Space Station (CSS) are two trends that will probably change the global image of the Chinese space program.”

While fears of a new space race unfold, could it be the role nations such as China and the UK to encourage international cooperation and joint space projects?

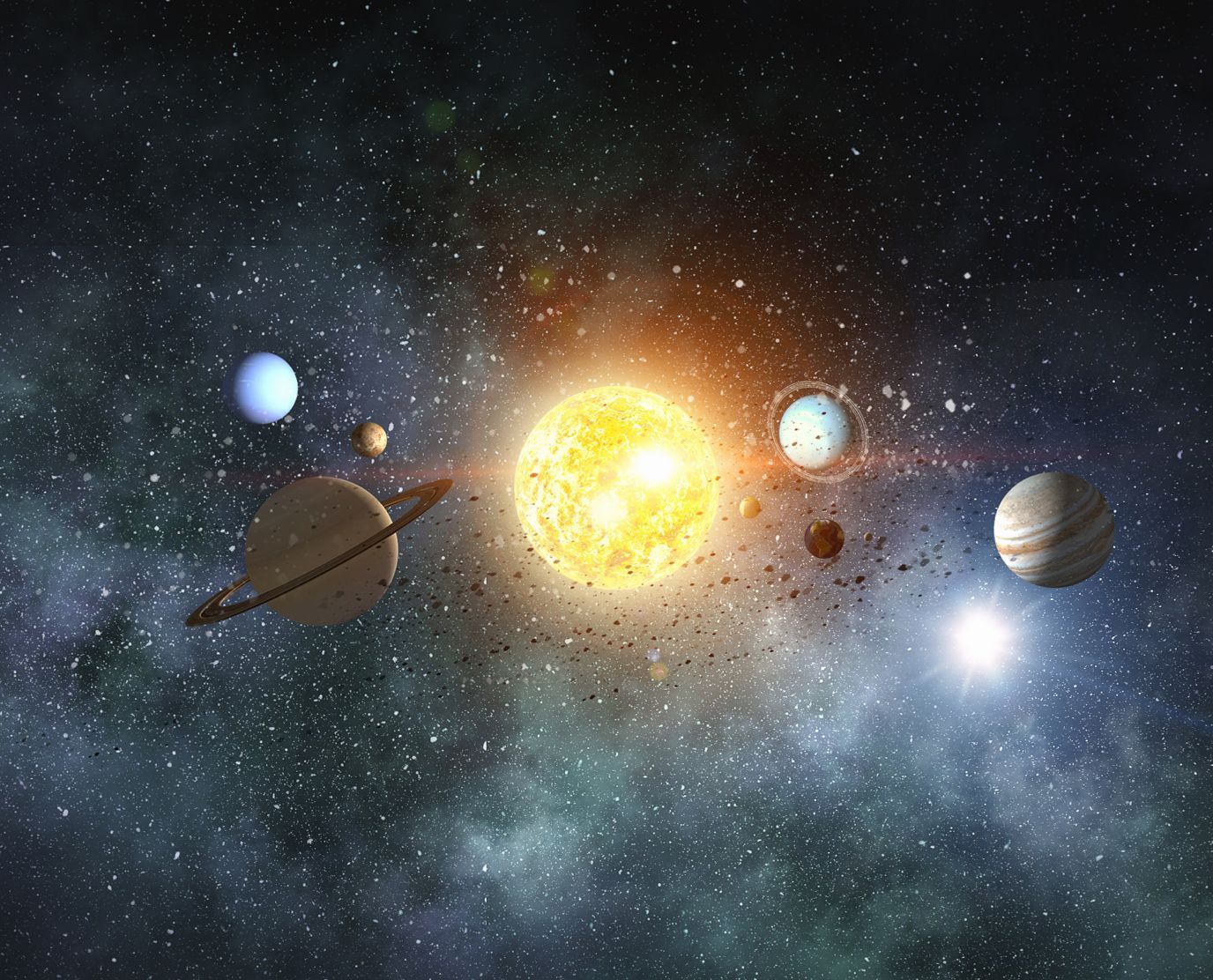

Chinese future for a solar system infrastructure

China are not only reaching out for cooperation on Tiangong, but also through their International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) programme, which rivals the US and their Artemis project in looking to establish a permanent lunar presence. South Africa were the latest nation to sign-up to ILRS. While the US has gained more partners though their proposed legal framework for space, the Artemis Accords, China have also this week laid out a bold vision for an infrastructure beyond the Moon, spanning the Solar System.

Under the plan laid out by Wang Wei, lead scientist from the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, they aim to establish a solar resources system by the year 2100, using and mining water and minerals from other celestial bodies. They would use gravitationally stable regions between the planets, moons and asteroids in order to branch out further, and construct resource facilities on places such as Mars and the moons of Jupiter.

While these plans may seem somewhat imaginative at this moment in time, we only have to look up and see the infrastructure already being developed in orbit. A long-term Chinese vision of interplanetary exploration and resource utilisation may become another element making them an attractive partner to work with in space.

US & ESA to relay with asteroids

Yet while China do have this grand vision of the future, NASA and ESA will soon be embarking of their own journeys to relay with different asteroids. Starting in October this year, NASA’s Psyche mission is due to launch between the 5th and 25th October. It will head to an asteroid of the same name and is due to arrive in 2029. There it will spend over two years studying the asteroid in order to understand the cores of planets, such as our own.

Asteroid Psyche had previously gained much attention when it gained a price tag of $10,000 quadrillion, due to its makeup of minerals such as iron and nickel. Humankind is still some years away from truly exploring the potential of asteroid mining, but Psyche has perhaps piqued interest in this area. Companies such as Astroforge and Transastra are amongst some commercial entities working towards developing celestial mining technology.

ESA have now assembled their own spacecraft due to relay with another asteroid, Dimorphos. The HERA spacecraft is due to launch in October next year and will follow-up on the impact of NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission, which impacted with the asteroid last September. The mission aimed to demonstrate how to gradually change the course of an asteroid as a means of planetary defence and reported impressive results. The September impact changed its orbit with its parent asteroid by 32 minutes. NASA had set a minimum successful time of 73 seconds.

While the vision of building space infrastructure might be what brings nations together, asteroid exploration and planetary defence may also be an area where to build more cooperation.

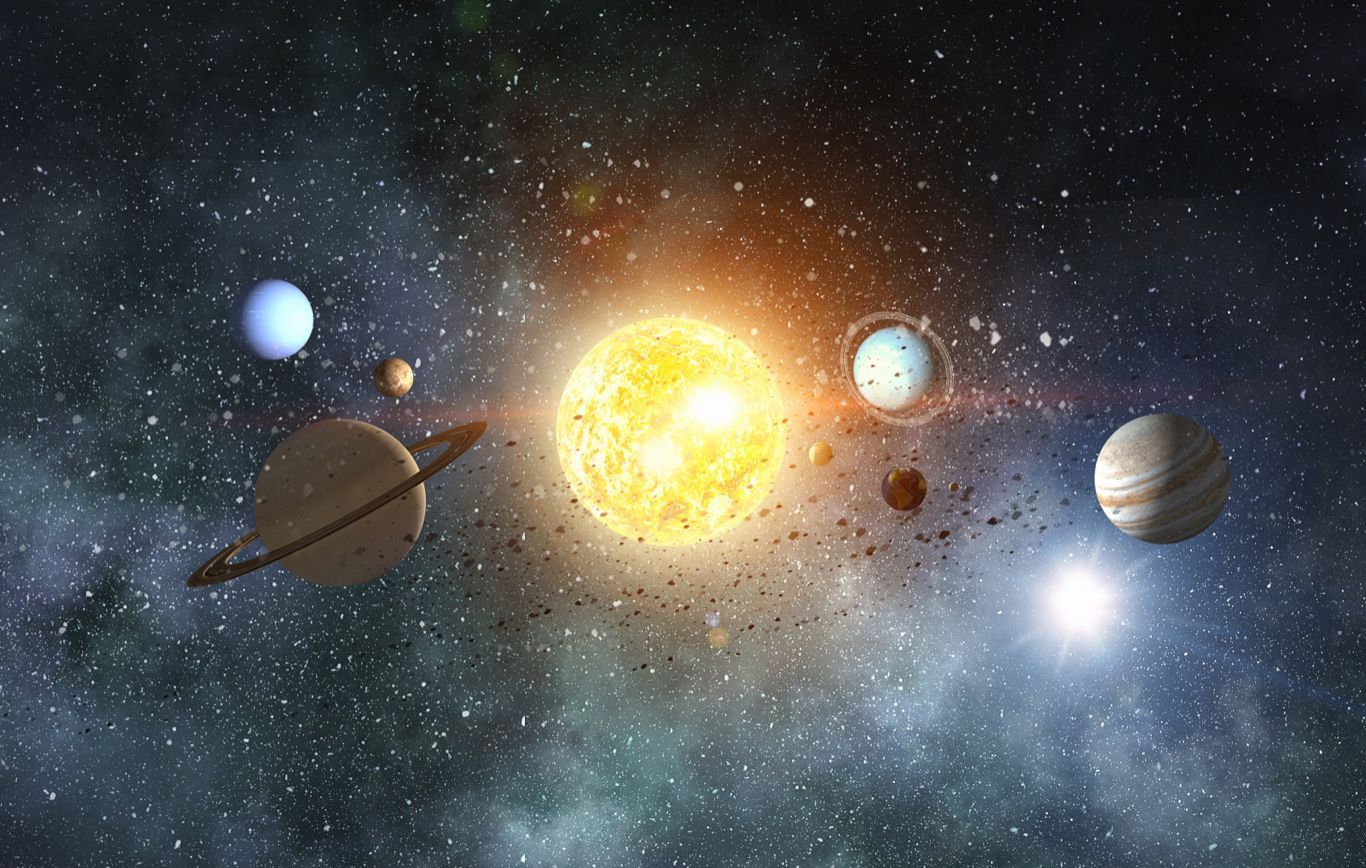

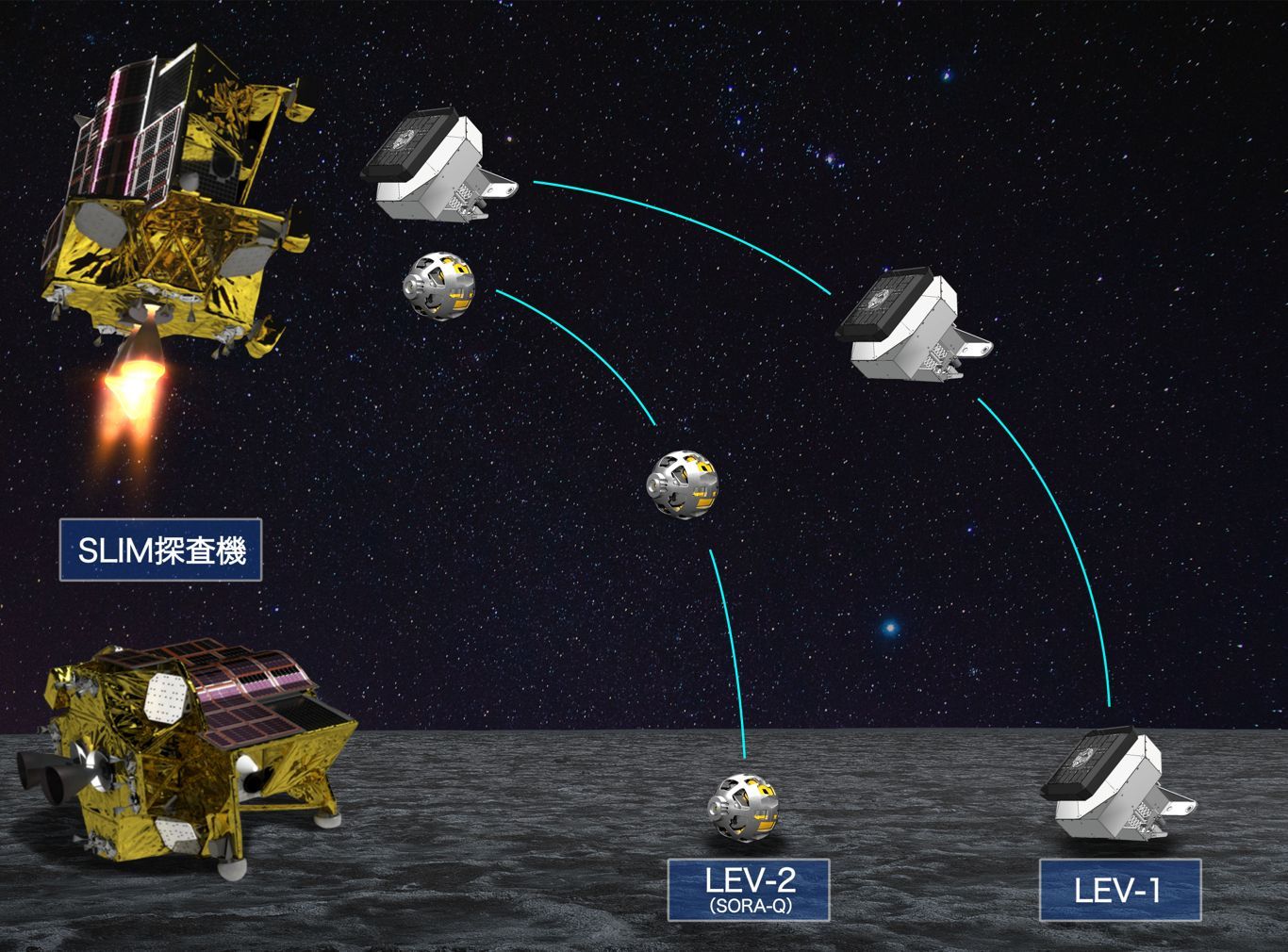

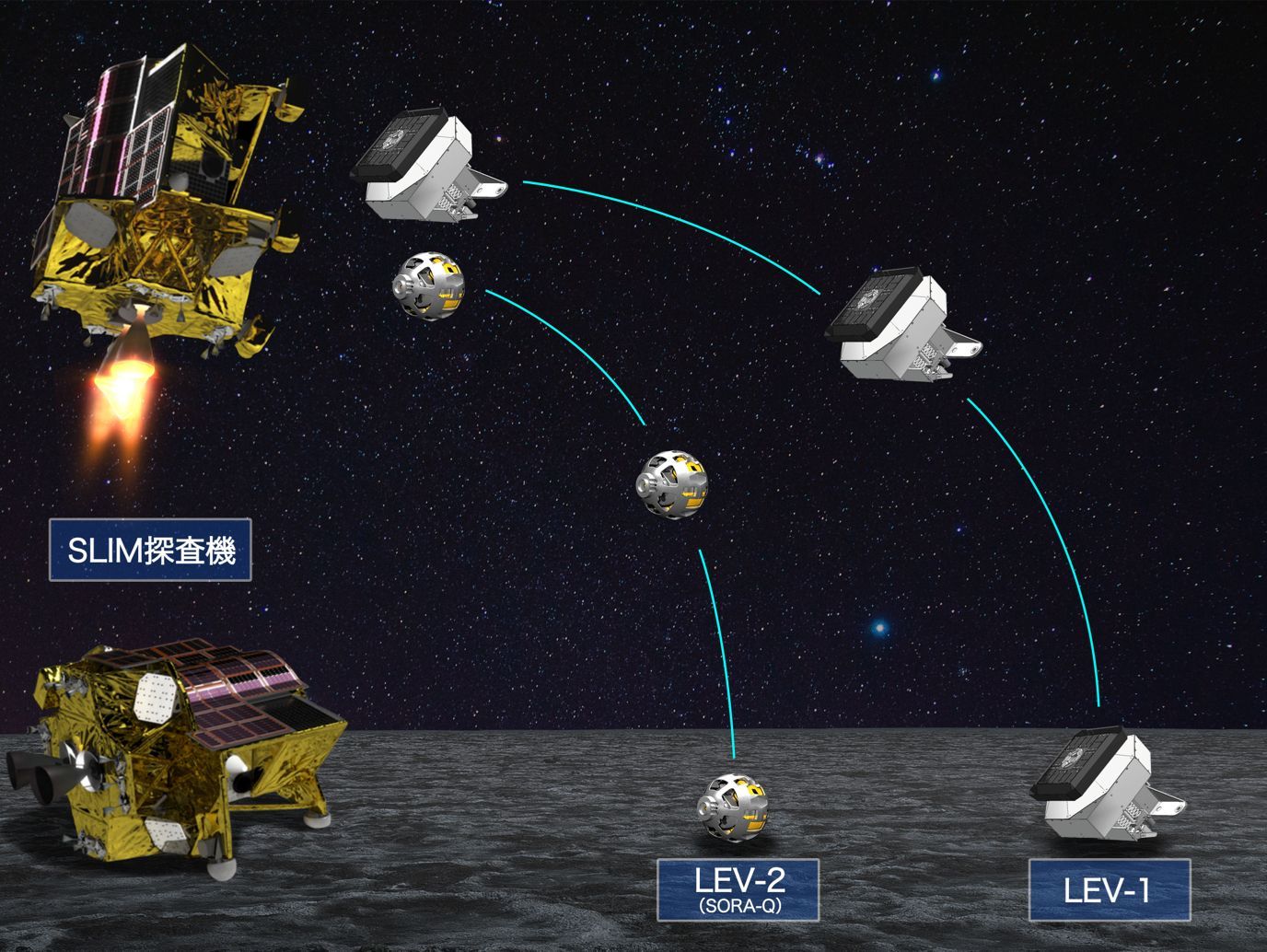

(Image: JAXA/TOMY Company/Sony Group Corporation/Doshisha University)

More entities heading to the Moon, Japan aim to be the fifth

On September 6th, Japan launched their attempt to become the fifth nation to successfully land on the Moon. The SLIM lunar lander will take a longer trajectory to the Moon, and should arrive in three to four months. The lander will carry out a precise landing on the surface, demonstrating new technology which will hopefully assist in carrying out a landing within 100m of its intended target.

Once on the surface, the lander will release two rovers to explore the lunar surface. Lunar Excursion Vehicle 1 (LEV-1) is a hopping rover, which will communicate directly with Earth, while LEV-2 is a small 250g rover with the ability to change its shape in order to traverse the surface.

Japan will be following in the footsteps of India, who made history in becoming the fourth nation to land on the Moon last month, with their Vikram lander. Upon arrival at the surface their Pragyan lunar rover was released and travelled over 100m, discovering the presence of iron, oxygen, sulphur and other elements. The rover and lander will now go into sleep mode for the two week long lunar night, with the hope that they can survive the -120C temperatures.

Interest in lunar exploration continued to spike this week as it was announced that Australia aim to launch a lunar rover as part of NASA’s 2026 Artemis mission, built as part of NASA’s Trailblazer program. The yet-to-be-named rover will collect samples of lunar soil, which NASA will then try and extract oxygen from.

Commercial lunar landing company, Intuitive Machines, are also gearing-up for launch in November and have recently announced that they have raised an additional $20 million through a stock sale. Their IM-1 lunar mission is die to launch with SpaceX on November 15th.

Missions such as Japan’s SLIM and India’s Chandrayaan-3 aim to better understand how to better navigate the lunar surface and source valuable resources such as water. Moreover, with a successful landing of IM-1, we may soon see the real beginnings of the commercialisation of the Moon.

Orbex (UK) looking to launch from Scotland (Image: Orbex)

Emerging leaders in launch market, growth of direct-to-cell technology

SpaceX may be increasing their grip on the launch market, but that isn’t to say there aren’t other dominant players emerging. New Zealand US-based launch company, Rocket Lab, have reached a milestone of their own in successfully carrying out the 40th launch of its Electron rocket.

Furthermore, the launch saw the company take further steps into the reusability market, reusing one of their Rutherford engines in the booster. The full booster was then later captured after it landed in the ocean, with the ultimate aim of reusing the whole first stage.

Another leader has been emerging in the way of US launch startup, Firefly Aerospace. Last week the company was put on notice as part of their responsive space-launch mission, Victus Nox, where they will be challenged to integrate a satellite onto their Alpha rocket and be ready for launch at short notice. They received more positive news this week as they have been selected to launch three satellites for L3 Harris Technologies in 2026. The satellites are being contracted by the US government and may see Firefly enter a profitable area, in being chosen to launch both government and commercial payloads.

Chinese commercial launch startups also appear to be growing in strength. This week Galactic Energy, based in Beijing, carried out the first sea-based launch by private Chinese launch manufacturer. CERES-1 successfully launched and deployed four satellites into orbit. China follows behind SpaceX in terms of launch numbers, but with the growth of its private sector, might be looking to gain some ground.

Europe are also not giving up on their quest for non-dependent launch capabilities. The debut launch of their long-awaited Ariane-6 rocket (replacement for Ariane-5) has been pushed back to 2024. However, it appears that commercial launch startups might be coming closer to filling the gap. Talking about the coming of new launch sites in the UK, Science minister George Freeman said that he thinks that “…Scotland could be the first country in Europe to launch.”

Companies such as Skyrora (UK), Orbex (UK) and Rocket Factory Augsburg (Germany) are planning on carrying out their maiden launches from Scotland in the near future.

While smaller launch startups cannot compete with SpaceX in terms of numbers, it may go to show that diversification, responsive technology and independant access to space may be what encourages the growth of new launch companies.

Direct-to-cell technology on the rise

Lastly, we are witnessing the continued growth of direct-to-cell (or direct-to-smartphone) technology, designed to give users global connectivity via satellites when off the terrestrial grid. This is already being provided by Apple in cooperation with Globalstar, incorporating SOS messaging on newer handsets, for example.

This week Japanese telecommunications operator, KDDI, announced a partnership with SpaceX in order to use their Starlink system to provide connectivity beyond 4G and 5G networks. Furthermore, Vodafone have announced that they will beta-test services using Amazon’s planned Kuiper mega-constellation next year, to increase the reach of its networks in Europe and Africa.

Direct-to-cell isn’t a new idea, but as we have previously assessed, should it be universally adopted for all new handsets, we could see a substantial knock-on effect for satellite usage, demand for launches and the space sector as a whole.

External Links

This Week

*News articles posted here are not property of ANASDA GmbH and belong to their respected owners. Postings here are external links only.

Our future in space

China to build infrastructure in solar system? (Image: Adobe)

08 September 2023

Agencies want cooperation, while Musk dominates launches. China map infrastructure for the Solar System

- Space News Roundup

It’s now long been seen that SpaceX are the frontrunners in the commercialisation of space, through reusable launches, establishing their Starlink satellite mega-constellation and becoming the go-to ride-share service into space. The launch of Starship will also see them play a key role in the Artemis lunar landing program and establish a path towards interplanetary travel.

Elon Musk recently claimed that SpaceX has exceeded last years launch numbers and transported 80% of all payload mass to orbit so far this year. Furthermore, their September 4th Starlink launch saw them set a new record for annual launches (62), beating a record previously set in 2022. By 2024, Musk aims to deliver 90% of all mass to orbit and once Starship is online, he expects that number to rise to 99%.

These figures truly are a testament to the sheer innovation and speed at which SpaceX have moved, opening-up access to space for more and at a much lower cost. However, that dominance isn’t necessarily being received well by all. A piece from the New Yorker claims that some think the tycoon holds too much power and influence.

We’ve also previously noted that some nations and agencies, such as ESA, may not favour relying on a single supply chain and rather establish their own, sovereign launch capabilities. It may also present a problem should SpaceX become embroiled in any kind of geopolitical dispute, such as the use of Starlink in Ukraine, and become a target of warfare. So despite this dominance, there may still be the desire for nations to diversify and allow room for more commercial entities to expand their capabilities.

SpaceX dominates but nations want to open-up for more cooperation

While SpaceX might aim to dominate the launch market, there is ongoing evidence of a willingness to open-up space for cooperative projects. The UK Space Agency is ploughing ahead with its plans under their International Bilateral Fund investments, and will allow the agency to work with the US, Canada, Australia, Japan, India, Singapore, South Africa and more.

They have recently announced collaborations with Australian partners on projects such as lunar regolith sampling, Earth observation and in-orbit servicing. In addition to this, the UK has announced a partnership with the US relating to electric space propulsion, involving Pulsar Fusion (UK) and the University of Michigan.

China also look to commit to using their orbital space station (Tiangong) as vessel for international cooperation. A report released on August 28th from the Department of the Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) stated that this use of Tiangong could change perceptions of Chinese intentions in space, saying that “The People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA’s) intention to allow civilian astronauts and nonstate-owned enterprise (SOE) companies to participate in the Chinese Space Station (CSS) are two trends that will probably change the global image of the Chinese space program.”

While fears of a new space race unfold, could it be the role nations such as China and the UK to encourage international cooperation and joint space projects?

Chinese future for a solar system infrastructure

China are not only reaching out for cooperation on Tiangong, but also through their International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) programme, which rivals the US and their Artemis project in looking to establish a permanent lunar presence. South Africa were the latest nation to sign-up to ILRS. While the US has gained more partners though their proposed legal framework for space, the Artemis Accords, China have also this week laid out a bold vision for an infrastructure beyond the Moon, spanning the Solar System.

Under the plan laid out by Wang Wei, lead scientist from the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, they aim to establish a solar resources system by the year 2100, using and mining water and minerals from other celestial bodies. They would use gravitationally stable regions between the planets, moons and asteroids in order to branch out further, and construct resource facilities on places such as Mars and the moons of Jupiter.

While these plans may seem somewhat imaginative at this moment in time, we only have to look up and see the infrastructure already being developed in orbit. A long-term Chinese vision of interplanetary exploration and resource utilisation may become another element making them an attractive partner to work with in space.

US & ESA to relay with asteroids

Yet while China do have this grand vision of the future, NASA and ESA will soon be embarking of their own journeys to relay with different asteroids. Starting in October this year, NASA’s Psyche mission is due to launch between the 5th and 25th October. It will head to an asteroid of the same name and is due to arrive in 2029. There it will spend over two years studying the asteroid in order to understand the cores of planets, such as our own.

Asteroid Psyche had previously gained much attention when it gained a price tag of $10,000 quadrillion, due to its makeup of minerals such as iron and nickel. Humankind is still some years away from truly exploring the potential of asteroid mining, but Psyche has perhaps piqued interest in this area. Companies such as Astroforge and Transastra are amongst some commercial entities working towards developing celestial mining technology.

ESA have now assembled their own spacecraft due to relay with another asteroid, Dimorphos. The HERA spacecraft is due to launch in October next year and will follow-up on the impact of NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission, which impacted with the asteroid last September. The mission aimed to demonstrate how to gradually change the course of an asteroid as a means of planetary defence and reported impressive results. The September impact changed its orbit with its parent asteroid by 32 minutes. NASA had set a minimum successful time of 73 seconds.

While the vision of building space infrastructure might be what brings nations together, asteroid exploration and planetary defence may also be an area where to build more cooperation.

(Image: JAXA/TOMY Company/Sony Group Corporation/Doshisha University)

More entities heading to the Moon, Japan aim to be the fifth

On September 6th, Japan launched their attempt to become the fifth nation to successfully land on the Moon. The SLIM lunar lander will take a longer trajectory to the Moon, and should arrive in three to four months. The lander will carry out a precise landing on the surface, demonstrating new technology which will hopefully assist in carrying out a landing within 100m of its intended target.

Once on the surface, the lander will release two rovers to explore the lunar surface. Lunar Excursion Vehicle 1 (LEV-1) is a hopping rover, which will communicate directly with Earth, while LEV-2 is a small 250g rover with the ability to change its shape in order to traverse the surface.

Japan will be following in the footsteps of India, who made history in becoming the fourth nation to land on the Moon last month, with their Vikram lander. Upon arrival at the surface their Pragyan lunar rover was released and travelled over 100m, discovering the presence of iron, oxygen, sulphur and other elements. The rover and lander will now go into sleep mode for the two week long lunar night, with the hope that they can survive the -120C temperatures.

Interest in lunar exploration continued to spike this week as it was announced that Australia aim to launch a lunar rover as part of NASA’s 2026 Artemis mission, built as part of NASA’s Trailblazer program. The yet-to-be-named rover will collect samples of lunar soil, which NASA will then try and extract oxygen from.

Commercial lunar landing company, Intuitive Machines, are also gearing-up for launch in November and have recently announced that they have raised an additional $20 million through a stock sale. Their IM-1 lunar mission is die to launch with SpaceX on November 15th.

Missions such as Japan’s SLIM and India’s Chandrayaan-3 aim to better understand how to better navigate the lunar surface and source valuable resources such as water. Moreover, with a successful landing of IM-1, we may soon see the real beginnings of the commercialisation of the Moon.

Orbex (UK) looking to launch from Scotland (Image: Orbex)

Emerging leaders in launch market, growth of direct-to-cell technology

SpaceX may be increasing their grip on the launch market, but that isn’t to say there aren’t other dominant players emerging. New Zealand US-based launch company, Rocket Lab, have reached a milestone of their own in successfully carrying out the 40th launch of its Electron rocket.

Furthermore, the launch saw the company take further steps into the reusability market, reusing one of their Rutherford engines in the booster. The full booster was then later captured after it landed in the ocean, with the ultimate aim of reusing the whole first stage.

Another leader has been emerging in the way of US launch startup, Firefly Aerospace. Last week the company was put on notice as part of their responsive space-launch mission, Victus Nox, where they will be challenged to integrate a satellite onto their Alpha rocket and be ready for launch at short notice. They received more positive news this week as they have been selected to launch three satellites for L3 Harris Technologies in 2026. The satellites are being contracted by the US government and may see Firefly enter a profitable area, in being chosen to launch both government and commercial payloads.

Chinese commercial launch startups also appear to be growing in strength. This week Galactic Energy, based in Beijing, carried out the first sea-based launch by private Chinese launch manufacturer. CERES-1 successfully launched and deployed four satellites into orbit. China follows behind SpaceX in terms of launch numbers, but with the growth of its private sector, might be looking to gain some ground.

Europe are also not giving up on their quest for non-dependent launch capabilities. The debut launch of their long-awaited Ariane-6 rocket (replacement for Ariane-5) has been pushed back to 2024. However, it appears that commercial launch startups might be coming closer to filling the gap. Talking about the coming of new launch sites in the UK, Science minister George Freeman said that he thinks that “…Scotland could be the first country in Europe to launch.”

Companies such as Skyrora (UK), Orbex (UK) and Rocket Factory Augsburg (Germany) are planning on carrying out their maiden launches from Scotland in the near future.

While smaller launch startups cannot compete with SpaceX in terms of numbers, it may go to show that diversification, responsive technology and independant access to space may be what encourages the growth of new launch companies.

Direct-to-cell technology on the rise

Lastly, we are witnessing the continued growth of direct-to-cell (or direct-to-smartphone) technology, designed to give users global connectivity via satellites when off the terrestrial grid. This is already being provided by Apple in cooperation with Globalstar, incorporating SOS messaging on newer handsets, for example.

This week Japanese telecommunications operator, KDDI, announced a partnership with SpaceX in order to use their Starlink system to provide connectivity beyond 4G and 5G networks. Furthermore, Vodafone have announced that they will beta-test services using Amazon’s planned Kuiper mega-constellation next year, to increase the reach of its networks in Europe and Africa.

Direct-to-cell isn’t a new idea, but as we have previously assessed, should it be universally adopted for all new handsets, we could see a substantial knock-on effect for satellite usage, demand for launches and the space sector as a whole.

Share this article

External Links

This Week

*News articles posted here are not property of ANASDA GmbH and belong to their respected owners. Postings here are external links only.

08 September 2023

Agencies want cooperation, while Musk dominates launches. China map infrastructure for the Solar System - Space News Roundup

China to build infrastructure in solar system? (Image: Adobe)

It’s now long been seen that SpaceX are the frontrunners in the commercialisation of space, through reusable launches, establishing their Starlink satellite mega-constellation and becoming the go-to ride-share service into space. The launch of Starship will also see them play a key role in the Artemis lunar landing program and establish a path towards interplanetary travel.

Elon Musk recently claimed that SpaceX has exceeded last years launch numbers and transported 80% of all payload mass to orbit so far this year. Furthermore, their September 4th Starlink launch saw them set a new record for annual launches (62), beating a record previously set in 2022. By 2024, Musk aims to deliver 90% of all mass to orbit and once Starship is online, he expects that number to rise to 99%.

These figures truly are a testament to the sheer innovation and speed at which SpaceX have moved, opening-up access to space for more and at a much lower cost. However, that dominance isn’t necessarily being received well by all. A piece from the New Yorker claims that some think the tycoon holds too much power and influence.

We’ve also previously noted that some nations and agencies, such as ESA, may not favour relying on a single supply chain and rather establish their own, sovereign launch capabilities. It may also present a problem should SpaceX become embroiled in any kind of geopolitical dispute, such as the use of Starlink in Ukraine, and become a target of warfare. So despite this dominance, there may still be the desire for nations to diversify and allow room for more commercial entities to expand their capabilities.

SpaceX dominates but nations want to open-up for more cooperation

While SpaceX might aim to dominate the launch market, there is ongoing evidence of a willingness to open-up space for cooperative projects. The UK Space Agency is ploughing ahead with its plans under their International Bilateral Fund investments, and will allow the agency to work with the US, Canada, Australia, Japan, India, Singapore, South Africa and more.

They have recently announced collaborations with Australian partners on projects such as lunar regolith sampling, Earth observation and in-orbit servicing. In addition to this, the UK has announced a partnership with the US relating to electric space propulsion, involving Pulsar Fusion (UK) and the University of Michigan.

China also look to commit to using their orbital space station (Tiangong) as vessel for international cooperation. A report released on August 28th from the Department of the Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) stated that this use of Tiangong could change perceptions of Chinese intentions in space, saying that “The People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA’s) intention to allow civilian astronauts and nonstate-owned enterprise (SOE) companies to participate in the Chinese Space Station (CSS) are two trends that will probably change the global image of the Chinese space program.”

While fears of a new space race unfold, could it be the role nations such as China and the UK to encourage international cooperation and joint space projects?

Chinese future for a solar system infrastructure

China are not only reaching out for cooperation on Tiangong, but also through their International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) programme, which rivals the US and their Artemis project in looking to establish a permanent lunar presence. South Africa were the latest nation to sign-up to ILRS. While the US has gained more partners though their proposed legal framework for space, the Artemis Accords, China have also this week laid out a bold vision for an infrastructure beyond the Moon, spanning the Solar System.

Under the plan laid out by Wang Wei, lead scientist from the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, they aim to establish a solar resources system by the year 2100, using and mining water and minerals from other celestial bodies. They would use gravitationally stable regions between the planets, moons and asteroids in order to branch out further, and construct resource facilities on places such as Mars and the moons of Jupiter.

While these plans may seem somewhat imaginative at this moment in time, we only have to look up and see the infrastructure already being developed in orbit. A long-term Chinese vision of interplanetary exploration and resource utilisation may become another element making them an attractive partner to work with in space.

US & ESA to relay with asteroids

Yet while China do have this grand vision of the future, NASA and ESA will soon be embarking of their own journeys to relay with different asteroids. Starting in October this year, NASA’s Psyche mission is due to launch between the 5th and 25th October. It will head to an asteroid of the same name and is due to arrive in 2029. There it will spend over two years studying the asteroid in order to understand the cores of planets, such as our own.

Asteroid Psyche had previously gained much attention when it gained a price tag of $10,000 quadrillion, due to its makeup of minerals such as iron and nickel. Humankind is still some years away from truly exploring the potential of asteroid mining, but Psyche has perhaps piqued interest in this area. Companies such as Astroforge and Transastra are amongst some commercial entities working towards developing celestial mining technology.

ESA have now assembled their own spacecraft due to relay with another asteroid, Dimorphos. The HERA spacecraft is due to launch in October next year and will follow-up on the impact of NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission, which impacted with the asteroid last September. The mission aimed to demonstrate how to gradually change the course of an asteroid as a means of planetary defence and reported impressive results. The September impact changed its orbit with its parent asteroid by 32 minutes. NASA had set a minimum successful time of 73 seconds.

While the vision of building space infrastructure might be what brings nations together, asteroid exploration and planetary defence may also be an area where to build more cooperation.

(Image: JAXA/TOMY Company/Sony Group Corporation/Doshisha University)

More entities heading to the Moon, Japan aim to be the fifth

On September 6th, Japan launched their attempt to become the fifth nation to successfully land on the Moon. The SLIM lunar lander will take a longer trajectory to the Moon, and should arrive in three to four months. The lander will carry out a precise landing on the surface, demonstrating new technology which will hopefully assist in carrying out a landing within 100m of its intended target.

Once on the surface, the lander will release two rovers to explore the lunar surface. Lunar Excursion Vehicle 1 (LEV-1) is a hopping rover, which will communicate directly with Earth, while LEV-2 is a small 250g rover with the ability to change its shape in order to traverse the surface.

Japan will be following in the footsteps of India, who made history in becoming the fourth nation to land on the Moon last month, with their Vikram lander. Upon arrival at the surface their Pragyan lunar rover was released and travelled over 100m, discovering the presence of iron, oxygen, sulphur and other elements. The rover and lander will now go into sleep mode for the two week long lunar night, with the hope that they can survive the -120C temperatures.

Interest in lunar exploration continued to spike this week as it was announced that Australia aim to launch a lunar rover as part of NASA’s 2026 Artemis mission, built as part of NASA’s Trailblazer program. The yet-to-be-named rover will collect samples of lunar soil, which NASA will then try and extract oxygen from.

Commercial lunar landing company, Intuitive Machines, are also gearing-up for launch in November and have recently announced that they have raised an additional $20 million through a stock sale. Their IM-1 lunar mission is die to launch with SpaceX on November 15th.

Missions such as Japan’s SLIM and India’s Chandrayaan-3 aim to better understand how to better navigate the lunar surface and source valuable resources such as water. Moreover, with a successful landing of IM-1, we may soon see the real beginnings of the commercialisation of the Moon.

Orbex (UK) looking to launch from Scotland (Image: Orbex)

Emerging leaders in launch market, growth of direct-to-cell technology

SpaceX may be increasing their grip on the launch market, but that isn’t to say there aren’t other dominant players emerging. New Zealand US-based launch company, Rocket Lab, have reached a milestone of their own in successfully carrying out the 40th launch of its Electron rocket.

Furthermore, the launch saw the company take further steps into the reusability market, reusing one of their Rutherford engines in the booster. The full booster was then later captured after it landed in the ocean, with the ultimate aim of reusing the whole first stage.

Another leader has been emerging in the way of US launch startup, Firefly Aerospace. Last week the company was put on notice as part of their responsive space-launch mission, Victus Nox, where they will be challenged to integrate a satellite onto their Alpha rocket and be ready for launch at short notice. They received more positive news this week as they have been selected to launch three satellites for L3 Harris Technologies in 2026. The satellites are being contracted by the US government and may see Firefly enter a profitable area, in being chosen to launch both government and commercial payloads.

Chinese commercial launch startups also appear to be growing in strength. This week Galactic Energy, based in Beijing, carried out the first sea-based launch by private Chinese launch manufacturer. CERES-1 successfully launched and deployed four satellites into orbit. China follows behind SpaceX in terms of launch numbers, but with the growth of its private sector, might be looking to gain some ground.

Europe are also not giving up on their quest for non-dependent launch capabilities. The debut launch of their long-awaited Ariane-6 rocket (replacement for Ariane-5) has been pushed back to 2024. However, it appears that commercial launch startups might be coming closer to filling the gap. Talking about the coming of new launch sites in the UK, Science minister George Freeman said that he thinks that “…Scotland could be the first country in Europe to launch.”

Companies such as Skyrora (UK), Orbex (UK) and Rocket Factory Augsburg (Germany) are planning on carrying out their maiden launches from Scotland in the near future.

While smaller launch startups cannot compete with SpaceX in terms of numbers, it may go to show that diversification, responsive technology and independant access to space may be what encourages the growth of new launch companies.

Direct-to-cell technology on the rise

Lastly, we are witnessing the continued growth of direct-to-cell (or direct-to-smartphone) technology, designed to give users global connectivity via satellites when off the terrestrial grid. This is already being provided by Apple in cooperation with Globalstar, incorporating SOS messaging on newer handsets, for example.

This week Japanese telecommunications operator, KDDI, announced a partnership with SpaceX in order to use their Starlink system to provide connectivity beyond 4G and 5G networks. Furthermore, Vodafone have announced that they will beta-test services using Amazon’s planned Kuiper mega-constellation next year, to increase the reach of its networks in Europe and Africa.

Direct-to-cell isn’t a new idea, but as we have previously assessed, should it be universally adopted for all new handsets, we could see a substantial knock-on effect for satellite usage, demand for launches and the space sector as a whole.

Share this article

External Links

This Week

*News articles posted here are not property of ANASDA GmbH and belong to their respected owners. Postings here are external links only.