05 October 2024

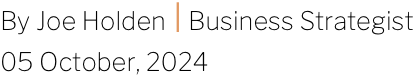

ESA Copernicus image of Greek wildfires (Image: ESA)

In the outcome of the highly anticipated UN Summit of the Future (22-23 September), world leaders adopted the Pact for the Future. The pact addresses a broad spectrum of issues, including peace and security, sustainable development, climate change, digital cooperation, and human rights. Notably, it also made critical commitments to space development, pledging to enhance cooperation in the peaceful use of outer space for the benefit of all humankind.

This commitment builds on the UN Outer Space Treaty (OST 1967), regarded as the cornerstone of international space law and recognised by over 100 countries, including all major spacefaring nations. In Action Point 56, the pact acknowledges the OST as the foundational framework for governing outer space. It reaffirms the need for the broadest possible compliance with the treaty while calling for new frameworks to address emerging challenges such as increasing space traffic, space debris, and the management of space resources.

The pact also recognises space as a key driver behind the 2030 Agenda to achieve the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), aiming to eradicate poverty and hunger, and to help build climate action, amongst others. This week also sees the beginning of World Space Week, with this year’s theme selected as “Space & Climate Change”, highlighting the “impact of space technology in our ongoing battle against climate change, emphasising the proactive role space exploration plays in enhancing our understanding and management of Earth’s climate.” (un.org)

Additionally, the pact recognises the vast opportunities space can offer for humanity and the planet, but it also acknowledges the significant challenges involved. One key element for the success of space exploration, and ensuring that space can benefit the planet, is the need for law-making to keep pace with innovation. It is essential to recognise that the space sector is experiencing rapid growth driven by commercial entities, which must remain committed to the common good of humanity.

Multi-stakeholder approaches to policy-making are now more crucial than ever in space, with the public also recognised as a key stakeholder. The pact reflects this notion by encouraging "the engagement of relevant private sector, civil society, and other relevant stakeholders" to contribute to intergovernmental processes. Space can continue and grow as a common benefit of humanity, but that success can only be pursued through responsible development and inclusivity.

Space-based solar power concept (Image: Airbus)

Space for Sustainable Goals: Space-Based Solar Power, In-Space Manufacturing, and Utilising Space to Combat Climate Change

This year, World Space Week aims to emphasise the effective application of space technology in enhancing our understanding of climate change. Satellite technology is crucial for Earth observation and climate monitoring, as well as for weather forecasting and disaster management. For instance, the EU's Copernicus Climate Change Service offers valuable climate data that informs policy recommendations.

Space can also play a significant role in rescue operations. This week, the U.S. commercial space infrastructure company Sierra Space received support from the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) for the development of “Ghost,” an orbital reentry vehicle designed to deliver cargo to any location on Earth within 90 minutes. The U.S. Air Force is exploring the concept of orbital warehouses that utilise reusable reentry vehicles, with the technology being also being promoted for rapid aid delivery in disaster-stricken areas.

Space is also being utilised for in-space manufacturing (ISM), by commercial entities such as Space Forge (UK) and Varda Space Technologies (US). Last year Varda carried out the successful manufacture of pharmaceutical drugs in-orbit, delivering the product back to Earth for the first time. Using the vacuum and zero gravity conditions of space provides an optimal environment for manufacture and can yield materials that are pure and without defects. This week Rocket Lab completed the construction of a spacecraft for Varda’s second ISM mission, aiming to launch in November.

Space Forge aims to utilise in-space manufacturing (ISM) to produce materials for semiconductors, a market experiencing rapidly growing demand and becoming an increasingly significant geopolitical concern. The company faced a setback when their first launch was lost during the failed Virgin Orbit mission in January 2023. Nevertheless, they have recently expanded their presence in the U.S. by opening an office in Florida. In November of last year, they were awarded £8 million by the UK Space Agency to establish a National Microgravity Research Centre.

There is also growing interest in using space to provide the solutions for our growing clean energy needs, in the battle against climate change and reaching carbon-neutral targets. Space-based solar power is a topic we often touch on, and is currently being explored by several agencies and companies. ESA is exploring its SOLARIS project, which calls for an in-orbit demonstration of SBSP by 2030, and in 2022 New Zealand-based company Emrod successfully demonstrated wireless energy beaming at Airbus’ Munich site.

Similarly, earlier this year UK-based company Space Solar carried out a lab demonstration showing how wireless energy-beaming from space could work. The demonstration is a key part of the UK’s own CASSIOPeiA space-based power plant concept.

Sustainable space for sustainable Earth

These are just a few areas where space is already serving as a means of protecting Earth and improving our lives. The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) provides insight into how space technology supports each of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They have also collaborated with the European Space Agency to develop a Space Solutions Compendium (SSC), which outlines how these goals can be achieved. You can find the SSC here.

However, while utilising space to build a sustainable future on Earth, we must ensure a responsible and sustainable future in space as well. As outlined in the Pact for the Future, space is experiencing a surge in activity, with the number of satellites skyrocketing. A Forbes article from July reported that there are over 10,000 active satellites in orbit, a number that has quadrupled over the past five years, largely due to SpaceX, whose Starlink mega-constellation accounts for half of all active satellites.

Furthermore, we are now witnessing the emergence of rival mega-constellations, such as Amazon’s Kuiper project. China is also developing its own, including the planned Guowang, G60, and Honghu-3 mega-constellations, each comprising over 10,000 satellites.

The rapidly increasing number of vehicles in orbit raises concerns about the growing abundance of space debris and the potential for collisions leading to a “Kessler effect.” This scenario describes how a series of collisions could trigger a permanent cascade of debris impacts, jeopardizing Earth’s orbit. ESA reports that there are currently around 40,500 pieces of debris larger than 10 cm and approximately 130 million smaller fragments orbiting Earth.

Efforts are underway to manage and clean up space debris, led by several commercial entities such as Astroscale (Japan) and Clearspace (Switzerland). In 2019, the UN Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) adopted its Long-Term Sustainability (LTS) guidelines, which include recommendations on measures to mitigate debris. Additionally, in May of this year, ESA received its first signatories for the Zero Debris Charter, a non-binding agreement established in response to a call from its member states at the 2022 ESA ministerial meeting to develop a “zero debris” approach for its missions.

While such efforts are underway, it is evident that the rate of innovation—particularly the rapid decrease in launch costs. This is a pressing concern, especially as we witness the development of outer space and the birth of a new lunar economy and infrastructure.

(Image: Pixabay)

New and emerging players in outer space, the need for equitable participation

The success in establishing the Outer Space Treaty in 1967 is due to the top-down approach needed during the heightened tensions of the Cold War. According to CD Johnson, Secure World Foundation, it is “largely the product of efforts by the United States and the USSR to agree on certain minimum standards and obligations to govern their competition” and was able to establish limited, but vital basic principles needed at the time, and still today, to allowing free access to space and prevent the placement of nuclear weapons in space.

However, today we face challenges that did not exist at the time the treaty was drafted, including a growing number of stakeholders and an increasing value placed on outer space for exploration and the resources it can provide. As interest and competition grow, the challenge of building and maintaining peaceful and sustainable uses of the Moon becomes increasingly complex.

The cadence of lunar missions is dramatically increasing, with the U.S. and China engaged in a race to return humans to the Moon and establish permanent lunar infrastructure. This week, China took another step toward its goal of a crewed landing by releasing images of its new spacesuits for the mission. Meanwhile, NASA discussed the testing of its Ground Test Unit, a rover prototype designed to assist in the development of the Lunar Terrain Vehicle, an unpressurised lunar rover concept being developed by competing teams led by Intuitive Machines, Lunar Outpost, and Venturi Astrolab.

India is also working toward returning to the Moon after its successful Chandrayaan-3 mission last year. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has revealed details of its Chandrayaan-4 lunar sample return mission, which is expected to launch in 2027. Commercial entities are also ramping up their activities, with Intuitive Machines preparing for its second commercial lunar landing in January, Japan’s iSpace aiming to launch before the end of this year, and this week, Astrobotic (U.S.) completed test communications for its Griffin lander, which is set to launch in 2025.

Need for more participation, awareness and visibility of outer space, in face of growing opportunities of outer space

The drive to expand our footprint beyond Earth is not only in our quest for knowledge and to expand our understanding of the cosmos, but as a necessity to answer some of humankind’s most pressing needs. According to Professor Brian Cox, utilising space resources such as asteroids may sound like fiction, but “it's extremely important that we do it, and as quickly as possible” in order to answer “civilisation’s thirst and requirement for more resources” (BBC, 2024).

Companies such as AstroForge (U.S.) are already launching and preparing for their next asteroid prospecting missions, while the commercial company Interlune (U.S.) has based its business model on mining and retrieving Helium-3 for use on Earth. The future of space exploration and exploitation is no longer led solely by a few leading space nations and agencies; it is increasingly driven by a growing number of nations and private entities. Moreover, space can and should benefit all humankind, offering solutions to many of our challenges, whether it involves monitoring our climate, sourcing energy, or accessing emerging space resources.

However, the benefits of space can only be realised through fair, responsible, and sustainable practices, which require the cooperation and participation of all stakeholders and beneficiaries, including governments, agencies, commercial companies, and civil society.

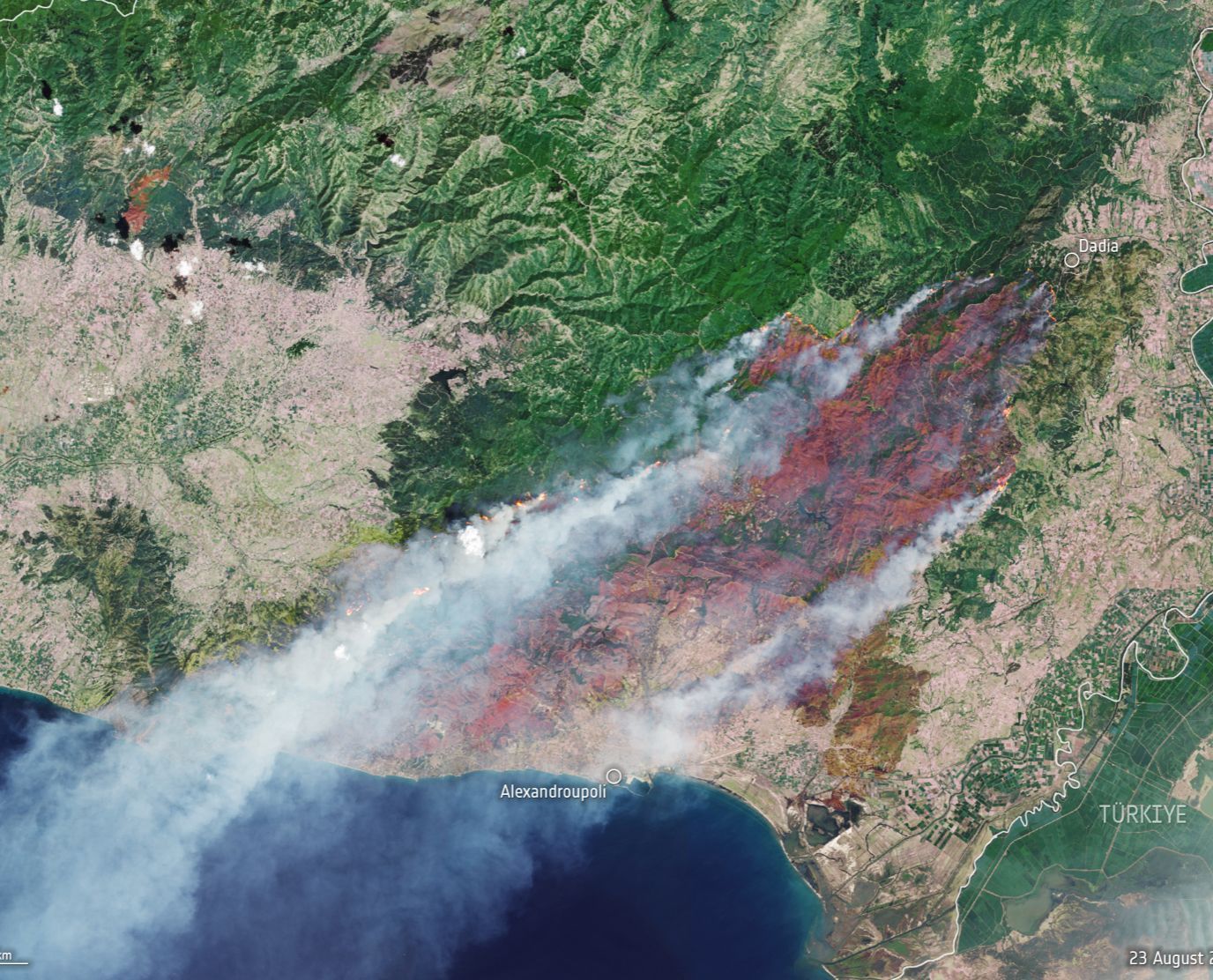

Chandrayaan-3 on the Moon (Image: ISRO)

05 October 2024

UN Pact Reaffirms the Outer Space Treaty, World Space Week and Sustainable Goals, Promoting Multi-Stakeholder Approaches to the Evolving Space Sector - Special Edition

In the outcome of the highly anticipated UN Summit of the Future (22-23 September), world leaders adopted the Pact for the Future. The pact addresses a broad spectrum of issues, including peace and security, sustainable development, climate change, digital cooperation, and human rights. Notably, it also made critical commitments to space development, pledging to enhance cooperation in the peaceful use of outer space for the benefit of all humankind.

This commitment builds on the UN Outer Space Treaty (OST 1967), regarded as the cornerstone of international space law and recognised by over 100 countries, including all major spacefaring nations. In Action Point 56, the pact acknowledges the OST as the foundational framework for governing outer space. It reaffirms the need for the broadest possible compliance with the treaty while calling for new frameworks to address emerging challenges such as increasing space traffic, space debris, and the management of space resources.

The pact also recognises space as a key driver behind the 2030 Agenda to achieve the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), aiming to eradicate poverty and hunger, and to help build climate action, amongst others. This week also sees the beginning of World Space Week, with this year’s theme selected as “Space & Climate Change”, highlighting the “impact of space technology in our ongoing battle against climate change, emphasising the proactive role space exploration plays in enhancing our understanding and management of Earth’s climate.” (un.org)

Additionally, the pact recognises the vast opportunities space can offer for humanity and the planet, but it also acknowledges the significant challenges involved. One key element for the success of space exploration, and ensuring that space can benefit the planet, is the need for law-making to keep pace with innovation. It is essential to recognise that the space sector is experiencing rapid growth driven by commercial entities, which must remain committed to the common good of humanity.

Multi-stakeholder approaches to policy-making are now more crucial than ever in space, with the public also recognised as a key stakeholder. The pact reflects this notion by encouraging "the engagement of relevant private sector, civil society, and other relevant stakeholders" to contribute to intergovernmental processes. Space

can continue and grow as a common benefit of humanity, but that success can only be pursued through responsible development and inclusivity.

Space-based solar power concept (Image: Airbus)

Space for Sustainable Goals: Space-Based Solar Power, In-Space Manufacturing, and Utilising Space to Combat Climate Change

This year, World Space Week aims to emphasise the effective application of space technology in enhancing our understanding of climate change. Satellite technology is crucial for Earth observation and climate monitoring, as well as for weather forecasting and disaster management. For instance, the EU's Copernicus Climate Change Service offers valuable climate data that informs policy recommendations.

Space can also play a significant role in rescue operations. This week, the U.S. commercial space infrastructure company Sierra Space received support from the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) for the development of “Ghost,” an orbital reentry vehicle designed to deliver cargo to any location on Earth within 90 minutes. The U.S. Air Force is exploring the concept of orbital warehouses that utilise reusable reentry vehicles, with the technology being also being promoted for rapid aid delivery in disaster-stricken areas.

Space is also being utilised for in-space manufacturing (ISM), by commercial entities such as Space Forge (UK) and Varda Space Technologies (US). Last year Varda carried out the successful manufacture of pharmaceutical drugs in-orbit, delivering the product back to Earth for the first time. Using the vacuum and zero gravity conditions of space provides an optimal environment for manufacture and can yield materials that are pure and without defects. This week Rocket Lab completed the construction of a spacecraft for Varda’s second ISM mission, aiming to launch in November.

Space Forge aims to utilise in-space manufacturing (ISM) to produce materials for semiconductors, a market experiencing rapidly growing demand and becoming an increasingly significant geopolitical concern. The company faced a setback when their first launch was lost during the failed Virgin Orbit mission in January 2023. Nevertheless, they have recently expanded their presence in the U.S. by opening an office in Florida. In November of last year, they were awarded £8 million by the UK Space Agency to establish a National Microgravity Research Centre.

There is also growing interest in using space to provide the solutions for our growing clean energy needs, in the battle against climate change and reaching carbon-neutral targets. Space-based solar power is a topic we often touch on, and is currently being explored by several agencies and companies. ESA is exploring its SOLARIS project, which calls for an in-orbit demonstration of SBSP by 2030, and in 2022 New Zealand-based company Emrod successfully demonstrated wireless energy beaming at Airbus’ Munich site.

Similarly, earlier this year UK-based company Space Solar carried out a lab demonstration showing how wireless energy-beaming from space could work. The demonstration is a key part of the UK’s own CASSIOPeiA space-based power plant concept.

Sustainable space for sustainable Earth

These are just a few areas where space is already serving as a means of protecting Earth and improving our lives. The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) provides insight into how space technology supports each of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They have also collaborated with the European Space Agency to develop a Space Solutions Compendium (SSC), which outlines how these goals can be achieved. You can find the SSC here.

However, while utilising space to build a sustainable future on Earth, we must ensure a responsible and sustainable future in space as well. As outlined in the Pact for the Future, space is experiencing a surge in activity, with the number of satellites skyrocketing. A Forbes article from July reported that there are over 10,000 active satellites in orbit, a number that has quadrupled over the past five years, largely due to SpaceX, whose Starlink mega-constellation accounts for half of all active satellites.

Furthermore, we are now witnessing the emergence of rival mega-constellations, such as Amazon’s Kuiper project. China is also developing its own, including the planned Guowang, G60, and Honghu-3 mega-constellations, each comprising over 10,000 satellites.

The rapidly increasing number of vehicles in orbit raises concerns about the growing abundance of space debris and the potential for collisions leading to a “Kessler effect.” This scenario describes how a series of collisions could trigger a permanent cascade of debris impacts, jeopardizing Earth’s orbit. ESA reports that there are currently around 40,500 pieces of debris larger than 10 cm and approximately 130 million smaller fragments orbiting Earth.

Efforts are underway to manage and clean up space debris, led by several commercial entities such as Astroscale (Japan) and Clearspace (Switzerland). In 2019, the UN Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) adopted its Long-Term Sustainability (LTS) guidelines, which include recommendations on measures to mitigate debris. Additionally, in May of this year, ESA received its first signatories for the Zero Debris Charter, a non-binding agreement established in response to a call from its member states at the 2022 ESA ministerial meeting to develop a “zero debris” approach for its missions.

While such efforts are underway, it is evident that the rate of innovation—particularly the rapid decrease in launch costs. This is a pressing concern, especially as we witness the development of outer space and the birth of a new lunar economy and infrastructure.

(Image: Pixabay)

How can legacy agencies keep pace in an ever-competitive space economy?

While the UK aims to lead in building a new European space architecture, Sinead O’Sullivan, writing in a recent Financial Times op-ed, highlights challenges facing both NASA and ESA. Her analysis draws from two reports—one by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and another by former European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi on European competitiveness.

O’Sullivan argues that both NASA and ESA, as large, publicly funded institutions, struggle to adapt quickly to modern economic and political realities (FT, 2024). NASA has increasingly turned to private companies, as seen with the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, but in doing so, it has lost talented engineers and scientists to the private sector. ESA, by contrast, has failed to attract enough private sector support.

O’Sullivan points to the launch sector as an example, where ESA's long-awaited Ariane-6 rocket has been delivered at a high cost for a vehicle that lacks reusability—a key factor in modern spaceflight efficiency.

As a solution, O’Sullivan proposes that NASA focus on long-term projects that serve humanity, while ESA should further incentivise private-sector collaboration and provide stronger support to space startups.

These strategies could prove crucial for both NASA and ESA, as the space industry is evolving at a rapid pace. Recent developments from nations like India and the UK demonstrate the determination of growing space nations, driven by nationally-funded programs that stimulate private innovation and growth.

Both agencies do of course see the immense value in the private sector and spearheading national programmes in space exploration. The US leads the way in utilising commercial technology for national space endeavours, such as through their Artemis programme, taking humans back to the Moon and establishing a permanent lunar infrastructure. ESA has only last year indicated its desire to utilise commercial launch services, and draw the curtain on the era of publicly-funded Ariane rockets, and also indicated their goal to establish a presence on the Moon within the next decade.

However, it will also be necessary to respond more quickly to the economic, political and geopolitical challenges that they now face in an expanding space industry.

Share this article

05 October 2024

UN Pact Reaffirms the Outer Space Treaty, World Space Week and Sustainable Goals, Promoting Multi-Stakeholder Approaches to the Evolving Space Sector - Special Edition

ESA Copernicus image of Greek wildfires (Image: ESA)

In the outcome of the highly anticipated UN Summit of the Future (22-23 September), world leaders adopted the Pact for the Future. The pact addresses a broad spectrum of issues, including peace and security, sustainable development, climate change, digital cooperation, and human rights. Notably, it also made critical commitments to space development, pledging to enhance cooperation in the peaceful use of outer space for the benefit of all humankind.

This commitment builds on the UN Outer Space Treaty (OST 1967), regarded as the cornerstone of international space law and recognised by over 100 countries, including all major spacefaring nations. In Action Point 56, the pact acknowledges the OST as the foundational framework for governing outer space. It reaffirms the need for the broadest possible compliance with the treaty while calling for new frameworks to address emerging challenges such as increasing space traffic, space debris, and the management of space resources.

The pact also recognises space as a key driver behind the 2030 Agenda to achieve the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), aiming to eradicate poverty and hunger, and to help build climate action, amongst others. This week also sees the beginning of World Space Week, with this year’s theme selected as “Space & Climate Change”, highlighting the “impact of space technology in our ongoing battle against climate change, emphasising the proactive role space exploration plays in enhancing our understanding and management of Earth’s climate.” (un.org)

Additionally, the pact recognises the vast opportunities space can offer for humanity and the planet, but it also acknowledges the significant challenges involved. One key element for the success of space exploration, and ensuring that space can benefit the planet, is the need for law-making to keep pace with innovation. It is essential to recognise that the space sector is experiencing rapid growth driven by commercial entities, which must remain committed to the common good of humanity.

Multi-stakeholder approaches to policy-making are now more crucial than ever in space, with the public also recognised as a key stakeholder. The pact reflects this notion by encouraging "the engagement of relevant private sector, civil society, and other relevant stakeholders" to contribute to intergovernmental processes. Space can continue and grow as a common benefit of humanity, but that success can only be pursued through responsible development and inclusivity.

Space-based solar power concept (Image: Airbus)

Space for Sustainable Goals: Space-Based Solar Power, In-Space Manufacturing, and Utilising Space to Combat Climate Change

This year, World Space Week aims to emphasise the effective application of space technology in enhancing our understanding of climate change. Satellite technology is crucial for Earth observation and climate monitoring, as well as for weather forecasting and disaster management. For instance, the EU's Copernicus Climate Change Service offers valuable climate data that informs policy recommendations.

Space can also play a significant role in rescue operations. This week, the U.S. commercial space infrastructure company Sierra Space received support from the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) for the development of “Ghost,” an orbital reentry vehicle designed to deliver cargo to any location on Earth within 90 minutes. The U.S. Air Force is exploring the concept of orbital warehouses that utilise reusable reentry vehicles, with the technology being also being promoted for rapid aid delivery in disaster-stricken areas.

Space is also being utilised for in-space manufacturing (ISM), by commercial entities such as Space Forge (UK) and Varda Space Technologies (US). Last year Varda carried out the successful manufacture of pharmaceutical drugs in-orbit, delivering the product back to Earth for the first time. Using the vacuum and zero gravity conditions of space provides an optimal environment for manufacture and can yield materials that are pure and without defects. This week Rocket Lab completed the construction of a spacecraft for Varda’s second ISM mission, aiming to launch in November.

Space Forge aims to utilise in-space manufacturing (ISM) to produce materials for semiconductors, a market experiencing rapidly growing demand and becoming an increasingly significant geopolitical concern. The company faced a setback when their first launch was lost during the failed Virgin Orbit mission in January 2023. Nevertheless, they have recently expanded their presence in the U.S. by opening an office in Florida. In November of last year, they were awarded £8 million by the UK Space Agency to establish a National Microgravity Research Centre.

There is also growing interest in using space to provide the solutions for our growing clean energy needs, in the battle against climate change and reaching carbon-neutral targets. Space-based solar power is a topic we often touch on, and is currently being explored by several agencies and companies. ESA is exploring its SOLARIS project, which calls for an in-orbit demonstration of SBSP by 2030, and in 2022 New Zealand-based company Emrod successfully demonstrated wireless energy beaming at Airbus’ Munich site.

Similarly, earlier this year UK-based company Space Solar carried out a lab demonstration showing how wireless energy-beaming from space could work. The demonstration is a key part of the UK’s own CASSIOPeiA space-based power plant concept.

Sustainable space for sustainable Earth

These are just a few areas where space is already serving as a means of protecting Earth and improving our lives. The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) provides insight into how space technology supports each of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They have also collaborated with the European Space Agency to develop a Space Solutions Compendium (SSC), which outlines how these goals can be achieved. You can find the SSC here.

However, while utilising space to build a sustainable future on Earth, we must ensure a responsible and sustainable future in space as well. As outlined in the Pact for the Future, space is experiencing a surge in activity, with the number of satellites skyrocketing. A Forbes article from July reported that there are over 10,000 active satellites in orbit, a number that has quadrupled over the past five years, largely due to SpaceX, whose Starlink mega-constellation accounts for half of all active satellites.

Furthermore, we are now witnessing the emergence of rival mega-constellations, such as Amazon’s Kuiper project. China is also developing its own, including the planned Guowang, G60, and Honghu-3 mega-constellations, each comprising over 10,000 satellites.

The rapidly increasing number of vehicles in orbit raises concerns about the growing abundance of space debris and the potential for collisions leading to a “Kessler effect.” This scenario describes how a series of collisions could trigger a permanent cascade of debris impacts, jeopardizing Earth’s orbit. ESA reports that there are currently around 40,500 pieces of debris larger than 10 cm and approximately 130 million smaller fragments orbiting Earth.

Efforts are underway to manage and clean up space debris, led by several commercial entities such as Astroscale (Japan) and Clearspace (Switzerland). In 2019, the UN Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) adopted its Long-Term Sustainability (LTS) guidelines, which include recommendations on measures to mitigate debris. Additionally, in May of this year, ESA received its first signatories for the Zero Debris Charter, a non-binding agreement established in response to a call from its member states at the 2022 ESA ministerial meeting to develop a “zero debris” approach for its missions.

While such efforts are underway, it is evident that the rate of innovation—particularly the rapid decrease in launch costs. This is a pressing concern, especially as we witness the development of outer space and the birth of a new lunar economy and infrastructure.

(Image: Pixabay)

New and emerging players in outer space, the need for equitable participation

The success in establishing the Outer Space Treaty in 1967 is due to the top-down approach needed during the heightened tensions of the Cold War. According to CD Johnson, Secure World Foundation, it is “largely the product of efforts by the United States and the USSR to agree on certain minimum standards and obligations to govern their competition” and was able to establish limited, but vital basic principles needed at the time, and still today, to allowing free access to space and prevent the placement of nuclear weapons in space.

However, today we face challenges that did not exist at the time the treaty was drafted, including a growing number of stakeholders and an increasing value placed on outer space for exploration and the resources it can provide. As interest and competition grow, the challenge of building and maintaining peaceful and sustainable uses of the Moon becomes increasingly complex.

The cadence of lunar missions is dramatically increasing, with the U.S. and China engaged in a race to return humans to the Moon and establish permanent lunar infrastructure. This week, China took another step toward its goal of a crewed landing by releasing images of its new spacesuits for the mission. Meanwhile, NASA discussed the testing of its Ground Test Unit, a rover prototype designed to assist in the development of the Lunar Terrain Vehicle, an unpressurised lunar rover concept being developed by competing teams led by Intuitive Machines, Lunar Outpost, and Venturi Astrolab.

India is also working toward returning to the Moon after its successful Chandrayaan-3 mission last year. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has revealed details of its Chandrayaan-4 lunar sample return mission, which is expected to launch in 2027. Commercial entities are also ramping up their activities, with Intuitive Machines preparing for its second commercial lunar landing in January, Japan’s iSpace aiming to launch before the end of this year, and this week, Astrobotic (U.S.) completed test communications for its Griffin lander, which is set to launch in 2025.

Need for more participation, awareness and visibility of outer space, in face of growing opportunities of outer space

The drive to expand our footprint beyond Earth is not only in our quest for knowledge and to expand our understanding of the cosmos, but as a necessity to answer some of humankind’s most pressing needs. According to Professor Brian Cox, utilising space resources such as asteroids may sound like fiction, but “it's extremely important that we do it, and as quickly as possible” in order to answer “civilisation’s thirst and requirement for more resources” (BBC, 2024).

Companies such as AstroForge (U.S.) are already launching and preparing for their next asteroid prospecting missions, while the commercial company Interlune (U.S.) has based its business model on mining and retrieving Helium-3 for use on Earth. The future of space exploration and exploitation is no longer led solely by a few leading space nations and agencies; it is increasingly driven by a growing number of nations and private entities. Moreover, space can and should benefit all humankind, offering solutions to many of our challenges, whether it involves monitoring our climate, sourcing energy, or accessing emerging space resources.

However, the benefits of space can only be realised through fair, responsible, and sustainable practices, which require the cooperation and participation of all stakeholders and beneficiaries, including governments, agencies, commercial companies, and civil society.

Share this article