Define Our Future

04 May 2024

(Unsplash)

This weekend, China aims to embark on the next stage of their ambitious long-term lunar exploration programme, with the highly anticipated launch of their Chang’e-6 mission, aiming to land on the Moon and retrieve samples of lunar regolith from the far-side for the first time. The 54-day mission will launch with a Long-March 5 rocket, and is composed of an orbiter, lander, ascending vehicle and reentry module.

The lander will collect the samples, with the ascending spacecraft then lifting them to the orbiter. This will then transfer them to the entry module, ready for its journey back to Earth. The mission is also supported by their Queqiao-2 communications relay satellite, which was launched into lunar orbit in March.

The landing attempt also precedes Chang’e-7 and 8, which will both launch before the end of the decade, first looking to the search for usable lunar resources, and the latter to explore how to utilise them. These steps are in anticipation of a first crewed landing in 2030, and plans to establish the first steps towards constructing a lunar base, under their International Lunar Research Station project, a vision supported by nations and organisations, including Russia, Pakistan, Egypt and South Africa.

Chang’e-6 comes amid growing lunar race

China’s latest lunar mission comes amid new, growing lunar race, with six other private and agency missions attempting to land on the Moon within the last 12 months. The US and Japan have recently disclosed plans for cooperation under the US Artemis project, aiming to launch Japanese astronauts to the Moon in 2028 and 2032. In return, Japan will provide a pressurised lunar rover, the Lunar Cruiser, being developed by Toyota.

While the US and NASA strategically utilise the Artemis project to forge new partnerships and advance their vision for regulatory alignment in outer space through the Artemis Accords, which boasts a significant lead over China in terms of signatories, it is the commercial sector that is also furnishing the US with considerable firepower in the new space race.

In February, Intuitive Machines proved the viability of launching cost-efficient, commercially-made lunar landers for the first time, and there’s a good chance that another three private US missions will launch before the end of the year. This will include a first landing attempt from Firefly Aerospace and their Blue Ghost lander, with NASA purchasing their services under the Commercial Lunar Payloads Services (CLPS) programme.

While Blue Ghost was built with the help of $112 million from NASA (provided through CLPS), Firefly CEO, Bill Weber, has this week detailed how he believes that in the future the company won’t require NASA funding, saying that government contracts will no longer be the “prime driver” and that there is “most definitely enough demand on the commercial side.”

This seems to be the case, especially observing the growing number of commercially-driven innovations for the Moon, such as Lonestar Data’s secure lunar data storage services, Nokia’s upcoming 4G LTE lunar network and Interlune’s Helium-3 mining plans, coupled with ongoing demand to transport agency payloads.

NASA finally seek commercial assistance for Mars missions

NASA are also seeing the benefit if employing commercial services for Martian exploration, after facing budgetary issues for their Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission. This week the agency issued 12 research tasks to private companies in order to support future missions to Mars. The companies include Firefly, Astrobotic, Blue Origin and Impulse Space, tasked with providing services such as small and large payload delivery, as well as surface imaging.

The studies don’t provide a guarantee that such services will annually be contracted, but following the trajectory from other sectors, such as launch and lunar exploration, it seems that private innovation will also take-on leadership in this area as well.

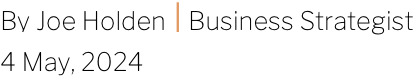

New Glenn rolled out in February (Image: Blue Origin)

HyImpulse takes flight, while Blue and Ariane expect upcoming debut launches

The launch sector has been the flagship of commercialisation in the space industry, providing cheaper, rapid access to space, spurring the growth of a new orbital infrastructure and rise of the era of New Space.

On Friday, German launch startup, HyImpulse, made their debut in this market with the first launch of their SR75 sounding rocket from the Koonibba Test Range in Southern Australia. The company, based in Baden-Württemberg, also saw an important milestone in the development of their hybrid rocket engines, utilising candle wax and liquid oxygen as propellant, and is an important step towards the development of their SL1 orbital launch vehicle. HyImpulse will be followed by other German startups, Isar Aerospace and Rocket Factory Augsburg, both also looking to carry-out debut launches this year from Norway and Scotland, respectively.

Blue Origin are also looking to finally launch their highly anticipated New Glenn heavy launch rocket this year, and have this week missed a date of no earlier than September 29th. New Glenn has the potential to provide real competition to the market leader, SpaceX’s Falcon-9. It also features a reusable first stage booster, and can carry around twice the payload capacity (45 tons) to low Earth orbit (LEO) as Falcon-9.

Interestingly, New Glenn’s first mission will be the NASA ESCAPADE mission, to launch a pair of smallsats that will be sent to orbit Mars.

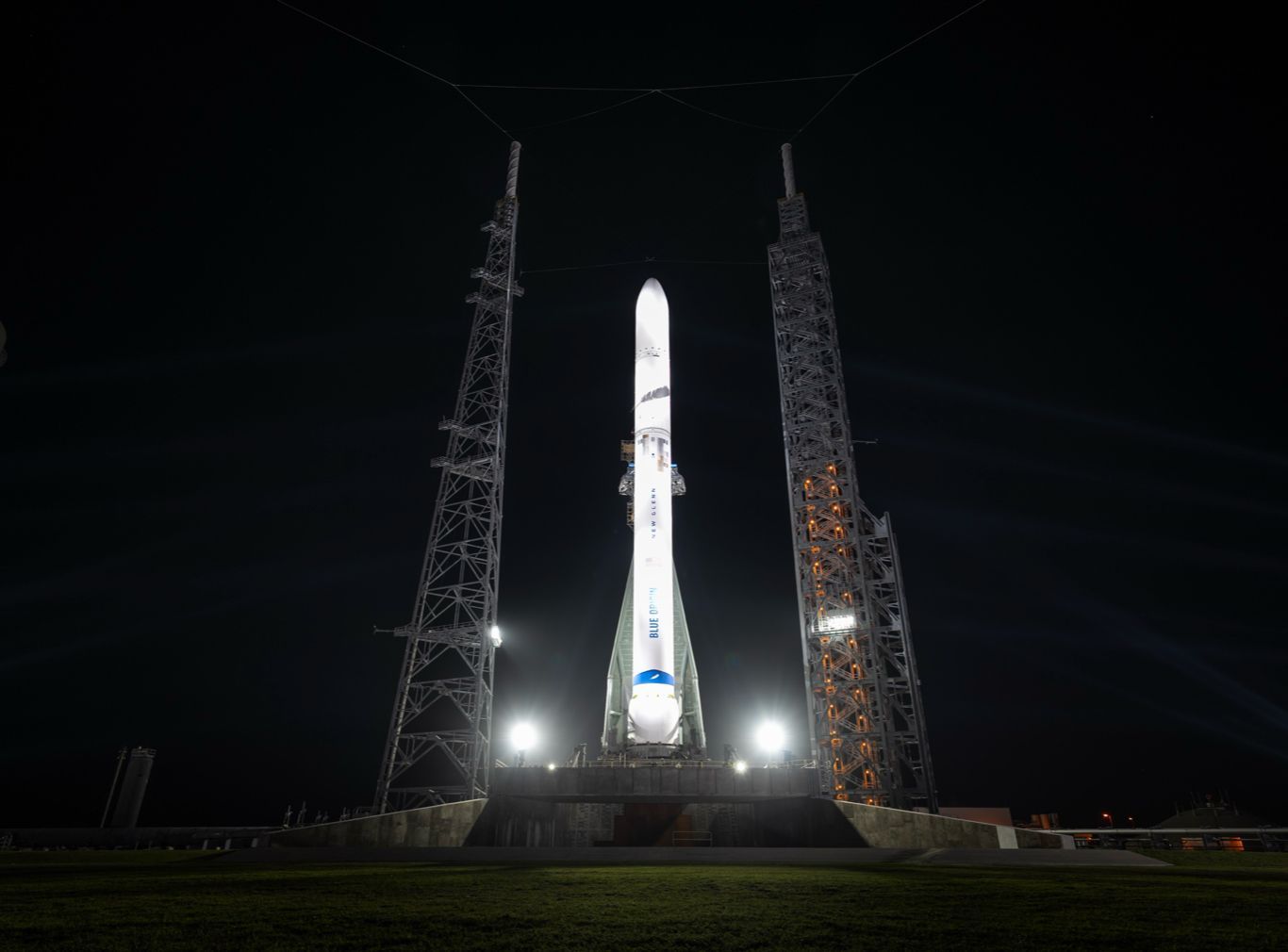

First image of orbital debris from Astroscale (Image: Astroscale)

Amidst new space race, orbital debris reaching critical levels

Chinese taikonauts on the Shenzhou 17 mission recently completed to spacewalks outside the Tiangong space station, carrying-out repairs after the station was struck by debris, leaving it with partial loss of power. On April 24th, the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) announced that the missions were a success and that Tiangong will be safeguarded against future such strikes.

This incident reflects a growing and significant problem that we all face, and follows another story in March, of a piece of space debris from the ISS reentering Earth’s atmosphere and smashing through the roof of a home in Florida.

A report published this week from Slingshot Aerospace has detailed concerns about the environment in orbit. According to the report, 12,597 spacecraft are in orbit, including 3,356 inactive satellites as of December 31, 2023, and nearly $1 billion in annual insurance losses. An ESA Space Environment Report from 2023 estimated that there are 36,500 pieces of debris greater than 10cm, and over 130 million pieces of tiny debris, between 1mm and 1cm large.

The scaling of satellite operations and the speed at which constellations are being developed is defining the new industrial revolution and quickly expanding end-user base for satellite swerves and products. However, last year alone saw nearly 3,000 new satellites deployed, 219 satellites becoming inactive, adding to the alarming situation and an ever-more crowded and contested low-Earth orbit.

A fear is that of orbit becoming so polluted that a continuous cascading and expanding series of collins takes place, known as the Kessler Effect, proposed by NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler in 1978.

First images of space debris provides evidence of critical times

This week leading debris removal startup, Japan-based Astroscale, released the world’s first publicly released image of space debris (above), taken by the Active Debris Removal by Astroscale-Japan (ADRAS-J) vehicle.

The photo shows the spent upper stage of a Japanese H-2A rocket, which ADRAS-J took from a proximity of just a few hundred metres. The Astroscale mission is designed to carry out close proximity operations and collect data on the debris, in order to inform the next stage; phase II removal of the debris.

There are initiatives being led in order to better manage, de-orbit and mitigate debris, not only from Astroscale. Swiss-based Clearspace recently updated plans for their first demonstration mission, Clearspace-1, after their intended target was itself stuck by debris.

This week, Australian company, Space Machines Company (SMC), announced a joint Australian-Indian mission to support debris management. The “Space MAITRI” mission will “demonstrate progress towards space debris management and a sustainable space future.” India will provide the launch vehicle, while SMC will develop an orbital servicing vehicle, with a vision of providing ‘roadside servicing in space,’ meaning spacecraft can be serviced, repaired and reused. This isn’t necessarily a new idea, with orbital refuelling companies, such as Orbit Fab, due to provide services to extend lives of satellites.

Opinion: While such efforts should be applauded, and we are to expect more in the way of sustainable policy, such as that from the upcoming EU Space Law, it will surely be necessary to scale these efforts, in order to have any chance of keeping pace with the exponential growth in satellite numbers. We often say that in oder for space to truly succeed for everyone, it will be essential for policy-making to keep pace with innovation.

However, it's also crucial that sustainable debris management efforts can keep up with the rapid deployment of satellites and exponential growth of this new orbital infrastructure.

Define Our Future

ADRAS-J (Astroscale)

04 May 2024

China Aims for Lunar Far-side Amid New Space Race; German Commercial Rocket Takes Flight; Tipping Point for Orbital Debris - Space News Roundup

This weekend, China aims to embark on the next stage of their ambitious long-term lunar exploration programme, with the highly anticipated launch of their Chang’e-6 mission, aiming to land on the Moon and retrieve samples of lunar regolith from the far-side for the first time. The 54-day mission will launch with a Long-March 5 rocket, and is composed of an orbiter, lander, ascending vehicle and reentry module.

The lander will collect the samples, with the ascending spacecraft then lifting them to the orbiter. This will then transfer them to the entry module, ready for its journey back to Earth. The mission is also supported by their Queqiao-2 communications relay satellite, which was launched into lunar orbit in March.

The landing attempt also precedes Chang’e-7 and 8, which will both launch before the end of the decade, first looking to the search for usable lunar resources, and the latter to explore how to utilise them. These steps are in anticipation of a first crewed landing in 2030, and plans to establish the first steps towards constructing a lunar base, under their International Lunar Research Station project, a vision supported by nations and organisations, including Russia, Pakistan, Egypt and South Africa.

Chang’e-6 comes amid growing lunar race

China’s latest lunar mission comes amid new, growing lunar race, with six other private and agency missions attempting to land on the Moon within the last 12 months. The US and Japan have recently disclosed plans for cooperation under the US Artemis project, aiming to launch Japanese astronauts to the Moon in 2028 and 2032. In return, Japan will provide a pressurised lunar rover, the Lunar Cruiser, being developed by Toyota.

While the US and NASA strategically utilise the Artemis project to forge new partnerships and advance their vision for regulatory alignment in outer space through the Artemis Accords, which boasts a significant lead over China in terms of signatories, it is the commercial sector that is also furnishing the US with considerable firepower in the new space race.

In February, Intuitive Machines proved the viability of launching cost-efficient, commercially-made lunar landers for the first time, and there’s a good chance that another three private US missions will launch before the end of the year. This will include a first landing attempt from Firefly Aerospace and their Blue Ghost lander, with NASA purchasing their services under the Commercial Lunar Payloads Services (CLPS) programme.

While Blue Ghost was built with the help of $112 million from NASA (provided through CLPS), Firefly CEO, Bill Weber, has this week detailed how he believes that in the future the company won’t require NASA funding, saying that government contracts will no longer be the “prime driver” and that there is “most definitely enough demand on the commercial side.”

This seems to be the case, especially observing the growing number of commercially-driven innovations for the Moon, such as Lonestar Data’s secure lunar data storage services, Nokia’s upcoming 4G LTE lunar network and Interlune’s Helium-3 mining plans, coupled with ongoing demand to transport agency payloads.

NASA finally seek commercial assistance for Mars missions

NASA are also seeing the benefit if employing commercial services for Martian exploration, after facing budgetary issues for their Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission. This week the agency issued 12 research tasks to private companies in order to support future missions to Mars. The companies include Firefly, Astrobotic, Blue Origin and Impulse Space, tasked with providing services such as small and large payload delivery, as well as surface imaging.

The studies don’t provide a guarantee that such services will annually be contracted, but following the trajectory from other sectors, such as launch and lunar exploration, it seems that private innovation will also take-on leadership in this area as well.

New Glenn rolled out in February (Image: Blue Origin)

HyImpulse takes flight, while Blue and Ariane expect upcoming debut launches

The launch sector has been the flagship of commercialisation in the space industry, providing cheaper, rapid access to space, spurring the growth of a new orbital infrastructure and rise of the era of New Space.

On Friday, German launch startup, HyImpulse, made their debut in this market with the first launch of their SR75 sounding rocket from the Koonibba Test Range in Southern Australia. The company, based in Baden-Württemberg, also saw an important milestone in the development of their hybrid rocket engines, utilising candle wax and liquid oxygen as propellant, and is an important step towards the development of their SL1 orbital launch vehicle. HyImpulse will be followed by other German startups, Isar Aerospace and Rocket Factory Augsburg, both also looking to carry-out debut launches this year from Norway and Scotland, respectively.

Blue Origin are also looking to finally launch their highly anticipated New Glenn heavy launch rocket this year, and have this week missed a date of no earlier than September 29th. New Glenn has the potential to provide real competition to the market leader, SpaceX’s Falcon-9. It also features a reusable first stage booster, and can carry around twice the payload capacity (45 tons) to low Earth orbit (LEO) as Falcon-9.

Interestingly, New Glenn’s first mission will be the NASA ESCAPADE mission, to launch a pair of smallsats that will be sent to orbit Mars.

First image of orbital debris from Astroscale (Image: Astroscale)

Amidst new space race, orbital debris reaching critical levels

Chinese taikonauts on the Shenzhou 17 mission recently completed to spacewalks outside the Tiangong space station, carrying-out repairs after the station was struck by debris, leaving it with partial loss of power. On April 24th, the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) announced that the missions were a success and that Tiangong will be safeguarded against future such strikes.

This incident reflects a growing and significant problem that we all face, and follows another story in March, of a piece of space debris from the ISS reentering Earth’s atmosphere and smashing through the roof of a home in Florida.

A report published this week from Slingshot Aerospace has detailed concerns about the environment in orbit. According to the report, 12,597 spacecraft are in orbit, including 3,356 inactive satellites as of December 31, 2023, and nearly $1 billion in annual insurance losses. An ESA Space Environment Report from 2023 estimated that there are 36,500 pieces of debris greater than 10cm, and over 130 million pieces of tiny debris, between 1mm and 1cm large.

The scaling of satellite operations and the speed at which constellations are being developed is defining the new industrial revolution and quickly expanding end-user base for satellite swerves and products. However, last year alone saw nearly 3,000 new satellites deployed, 219 satellites becoming inactive, adding to the alarming situation and an ever-more crowded and contested low-Earth orbit.

A fear is that of orbit becoming so polluted that a continuous cascading and expanding series of collins takes place, known as the Kessler Effect, proposed by NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler in 1978.

First images of space debris provides evidence of critical times

This week leading debris removal startup, Japan-based Astroscale, released the world’s first publicly released image of space debris (above), taken by the Active Debris Removal by Astroscale-Japan (ADRAS-J) vehicle.

The photo shows the spent upper stage of a Japanese H-2A rocket, which ADRAS-J took from a proximity of just a few hundred metres. The Astroscale mission is designed to carry out close proximity operations and collect data on the debris, in order to inform the next stage; phase II removal of the debris.

There are initiatives being led in order to better manage, de-orbit and mitigate debris, not only from Astroscale. Swiss-based Clearspace recently updated plans for their first demonstration mission, Clearspace-1, after their intended target was itself stuck by debris.

This week, Australian company, Space Machines Company (SMC), announced a joint Australian-Indian mission to support debris management. The “Space MAITRI” mission will “demonstrate progress towards space debris management and a sustainable space future.” India will provide the launch vehicle, while SMC will develop an orbital servicing vehicle, with a vision of providing ‘roadside servicing in space,’ meaning spacecraft can be serviced, repaired and reused. This isn’t necessarily a new idea, with orbital refuelling companies, such as Orbit Fab, due to provide services to extend lives of satellites.

Opinion: While such efforts should be applauded, and we are to expect more in the way of sustainable policy, such as that from the upcoming EU Space Law, it will surely be necessary to scale these efforts, in order to have any chance of keeping pace with the exponential growth in satellite numbers. We often say that in oder for space to truly succeed for everyone, it will be essential for policy-making to keep pace with innovation.

However, it's also crucial that sustainable debris management efforts can keep up with the rapid deployment of satellites and exponential growth of this new orbital infrastructure.

Share this article

05 May 2024

China Aims for Lunar Far-side Amid New Space Race; German Commercial Rocket Takes Flight; Tipping Point for Orbital Debris - Space News Roundup

(Unsplash)

This weekend, China aims to embark on the next stage of their ambitious long-term lunar exploration programme, with the highly anticipated launch of their Chang’e-6 mission, aiming to land on the Moon and retrieve samples of lunar regolith from the far-side for the first time. The 54-day mission will launch with a Long-March 5 rocket, and is composed of an orbiter, lander, ascending vehicle and reentry module.

The lander will collect the samples, with the ascending spacecraft then lifting them to the orbiter. This will then transfer them to the entry module, ready for its journey back to Earth. The mission is also supported by their Queqiao-2 communications relay satellite, which was launched into lunar orbit in March.

The landing attempt also precedes Chang’e-7 and 8, which will both launch before the end of the decade, first looking to the search for usable lunar resources, and the latter to explore how to utilise them. These steps are in anticipation of a first crewed landing in 2030, and plans to establish the first steps towards constructing a lunar base, under their International Lunar Research Station project, a vision supported by nations and organisations, including Russia, Pakistan, Egypt and South Africa.

Chang’e-6 comes amid growing lunar race

China’s latest lunar mission comes amid new, growing lunar race, with six other private and agency missions attempting to land on the Moon within the last 12 months. The US and Japan have recently disclosed plans for cooperation under the US Artemis project, aiming to launch Japanese astronauts to the Moon in 2028 and 2032. In return, Japan will provide a pressurised lunar rover, the Lunar Cruiser, being developed by Toyota.

While the US and NASA strategically utilise the Artemis project to forge new partnerships and advance their vision for regulatory alignment in outer space through the Artemis Accords, which boasts a significant lead over China in terms of signatories, it is the commercial sector that is also furnishing the US with considerable firepower in the new space race.

In February, Intuitive Machines proved the viability of launching cost-efficient, commercially-made lunar landers for the first time, and there’s a good chance that another three private US missions will launch before the end of the year. This will include a first landing attempt from Firefly Aerospace and their Blue Ghost lander, with NASA purchasing their services under the Commercial Lunar Payloads Services (CLPS) programme.

While Blue Ghost was built with the help of $112 million from NASA (provided through CLPS), Firefly CEO, Bill Weber, has this week detailed how he believes that in the future the company won’t require NASA funding, saying that government contracts will no longer be the “prime driver” and that there is “most definitely enough demand on the commercial side.”

This seems to be the case, especially observing the growing number of commercially-driven innovations for the Moon, such as Lonestar Data’s secure lunar data storage services, Nokia’s upcoming 4G LTE lunar network and Interlune’s Helium-3 mining plans, coupled with ongoing demand to transport agency payloads.

NASA finally seek commercial assistance for Mars missions

NASA are also seeing the benefit if employing commercial services for Martian exploration, after facing budgetary issues for their Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission. This week the agency issued 12 research tasks to private companies in order to support future missions to Mars. The companies include Firefly, Astrobotic, Blue Origin and Impulse Space, tasked with providing services such as small and large payload delivery, as well as surface imaging.

The studies don’t provide a guarantee that such services will annually be contracted, but following the trajectory from other sectors, such as launch and lunar exploration, it seems that private innovation will also take-on leadership in this area as well.

New Glenn rolled out in February (Image: Blue Origin)

HyImpulse takes flight, while Blue and Ariane expect upcoming debut launches

The launch sector has been the flagship of commercialisation in the space industry, providing cheaper, rapid access to space, spurring the growth of a new orbital infrastructure and rise of the era of New Space.

On Friday, German launch startup, HyImpulse, made their debut in this market with the first launch of their SR75 sounding rocket from the Koonibba Test Range in Southern Australia. The company, based in Baden-Württemberg, also saw an important milestone in the development of their hybrid rocket engines, utilising candle wax and liquid oxygen as propellant, and is an important step towards the development of their SL1 orbital launch vehicle. HyImpulse will be followed by other German startups, Isar Aerospace and Rocket Factory Augsburg, both also looking to carry-out debut launches this year from Norway and Scotland, respectively.

Blue Origin are also looking to finally launch their highly anticipated New Glenn heavy launch rocket this year, and have this week missed a date of no earlier than September 29th. New Glenn has the potential to provide real competition to the market leader, SpaceX’s Falcon-9. It also features a reusable first stage booster, and can carry around twice the payload capacity (45 tons) to low Earth orbit (LEO) as Falcon-9.

Interestingly, New Glenn’s first mission will be the NASA ESCAPADE mission, to launch a pair of smallsats that will be sent to orbit Mars.

First image of orbital debris from Astroscale (Image: Astroscale)

Amidst new space race, orbital debris reaching critical levels

Chinese taikonauts on the Shenzhou 17 mission recently completed to spacewalks outside the Tiangong space station, carrying-out repairs after the station was struck by debris, leaving it with partial loss of power. On April 24th, the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) announced that the missions were a success and that Tiangong will be safeguarded against future such strikes.

This incident reflects a growing and significant problem that we all face, and follows another story in March, of a piece of space debris from the ISS reentering Earth’s atmosphere and smashing through the roof of a home in Florida.

A report published this week from Slingshot Aerospace has detailed concerns about the environment in orbit. According to the report, 12,597 spacecraft are in orbit, including 3,356 inactive satellites as of December 31, 2023, and nearly $1 billion in annual insurance losses. An ESA Space Environment Report from 2023 estimated that there are 36,500 pieces of debris greater than 10cm, and over 130 million pieces of tiny debris, between 1mm and 1cm large.

The scaling of satellite operations and the speed at which constellations are being developed is defining the new industrial revolution and quickly expanding end-user base for satellite swerves and products. However, last year alone saw nearly 3,000 new satellites deployed, 219 satellites becoming inactive, adding to the alarming situation and an ever-more crowded and contested low-Earth orbit.

A fear is that of orbit becoming so polluted that a continuous cascading and expanding series of collins takes place, known as the Kessler Effect, proposed by NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler in 1978.

First images of space debris provides evidence of critical times

This week leading debris removal startup, Japan-based Astroscale, released the world’s first publicly released image of space debris (above), taken by the Active Debris Removal by Astroscale-Japan (ADRAS-J) vehicle.

The photo shows the spent upper stage of a Japanese H-2A rocket, which ADRAS-J took from a proximity of just a few hundred metres. The Astroscale mission is designed to carry out close proximity operations and collect data on the debris, in order to inform the next stage; phase II removal of the debris.

There are initiatives being led in order to better manage, de-orbit and mitigate debris, not only from Astroscale. Swiss-based Clearspace recently updated plans for their first demonstration mission, Clearspace-1, after their intended target was itself stuck by debris.

This week, Australian company, Space Machines Company (SMC), announced a joint Australian-Indian mission to support debris management. The “Space MAITRI” mission will “demonstrate progress towards space debris management and a sustainable space future.” India will provide the launch vehicle, while SMC will develop an orbital servicing vehicle, with a vision of providing ‘roadside servicing in space,’ meaning spacecraft can be serviced, repaired and reused. This isn’t necessarily a new idea, with orbital refuelling companies, such as Orbit Fab, due to provide services to extend lives of satellites.

Opinion: While such efforts should be applauded, and we are to expect more in the way of sustainable policy, such as that from the upcoming EU Space Law, it will surely be necessary to scale these efforts, in order to have any chance of keeping pace with the exponential growth in satellite numbers. We often say that in oder for space to truly succeed for everyone, it will be essential for policy-making to keep pace with innovation.

However, it's also crucial that sustainable debris management efforts can keep up with the rapid deployment of satellites and exponential growth of this new orbital infrastructure.

Share this article