03 November 2023

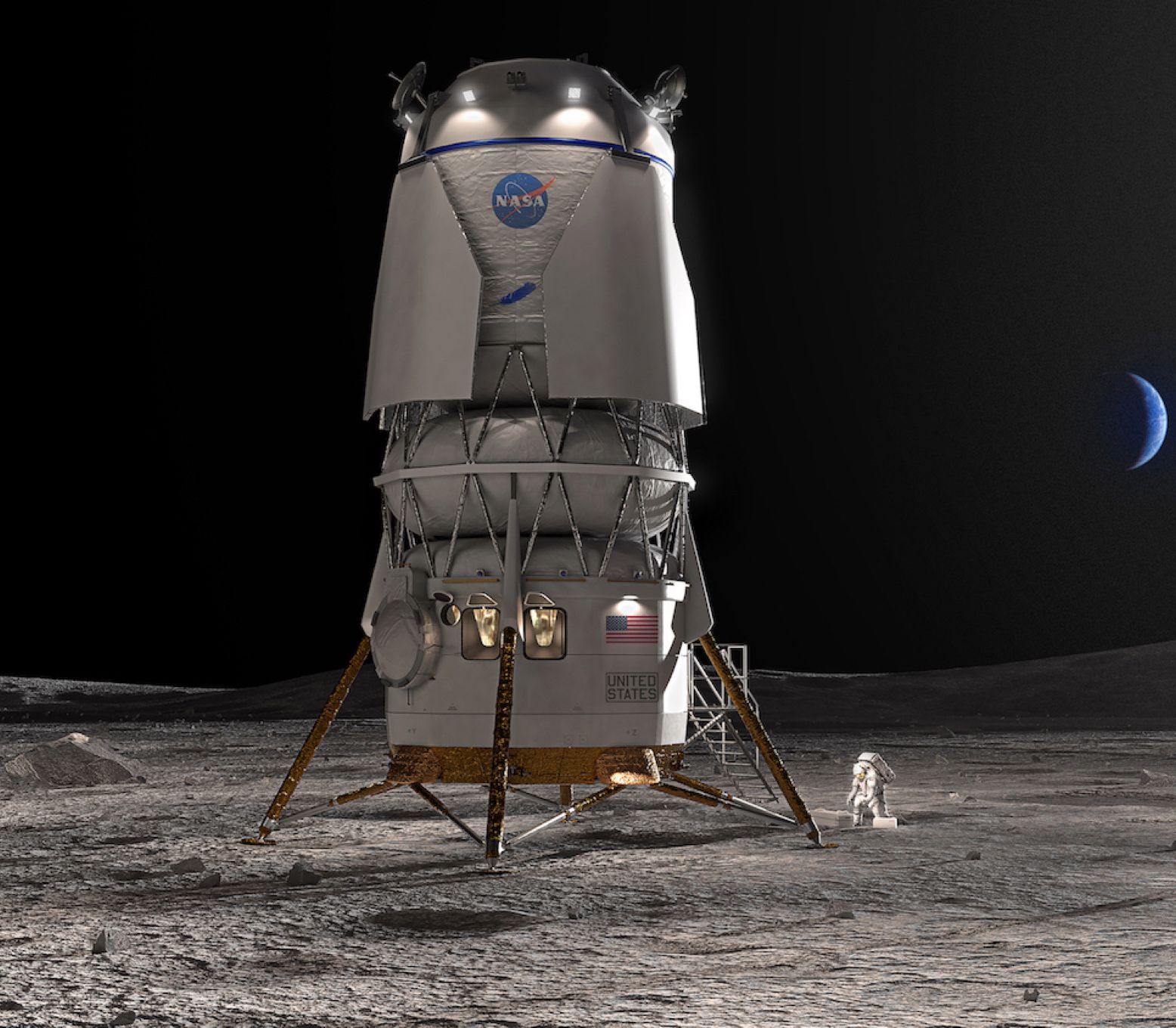

Illustration of Blue Origin's Blue Moon Lander (Blue Origin)

With an increasing number of public and private missions heading to the Moon, we are witnessing the birth of the new lunar economy. The head of the European Space Agency this week expressed the need for the continent not to “miss the train”. Joseph Aschbacher commented on the European plan for a lunar base, insisting “it will happen”, and that in Europe there are “a lot” of companies seeing the potential on the Moon, hinting that the private sector will have a leading role to play.

He did admit that the European space budget may need to be increased in order to achieve a crewed landing on the Moon, but with the necessary resources they may achieve this sometime in the next decade.

Moreover, he expressed the urgency of the situation, outlining that this is time time to act, insisting that Europe cannot afford to miss out on such opportunities, as it has done before. “If we don’t do it, then exactly the same will happen as happened in chips, IT or other domains where Europe [has] not invested” he said.

Commercial entities are already pressing ahead with their plans on capitalising the new lunar economy, as seen through companies such as Qosmosys, who recently competed a $100 million funding towards their lunar exploration project. The Singapore-based company aim to use their own ZeusX spacecraft to develop infrastructure in space and prioritise “the commercial and financial potential of the Moon economy”, with a particular focus on the extraction of minerals such as Helium-3.

Sierra Space CEO, Tom Vice, once said that there is an industrial revolution going on “250 miles above our heads.” This is certainly true, witnessed through the growing number of commercial entities driving the industry forwards, building a rapidly growing infrastructure in-orbit. But now we are looking beyond only Earth orbit, and the next stop is the Moon.

Founder of Scout Ventures, Brad Harrison, summed this up well when recently while commenting on their funding efforts for Lonestar Data Holdings, saying that they believe that the lunar economy is “the next whitespace in the New Space Economy.”

Intuitive Machines delay lunar launch, setting up possibility of commercial Moon race

We’re set to see a flurry of activity on the Moon, beginning with commercial companies Intuitive Machines (US) and Astrobotic (US). The former were initially looking to launch this month but have now delayed the mission until January, while Astrobotc have a launch window opening on Christmas Eve.

This opens up the possibility of a commercial Moon race, similar to that between India and Russia earlier this year. While Astrobotic may launch sooner, they are launching on a new rocket, the ULA Vulcan, perhaps making it more prone to technical delays. Furthermore, they take a slightly longer journey to the surface, around 30 days, compared to Intuitive Machines who will take around 7 days.

Blue Origin have also been making moves towards the development of their own commercial lander, named “Blue Moon”. This week the company released images of its prototype of the Blue Moon Mark 1 lander. It will be capable carrying three metric tons to the lunar surface, with a Mark 2 version due to carry crew the surface for the first time as part of the Artemis programme, currently set for 2029. Earlier Artemis missions will use a modified version of SpaceX’s Starship for the landing.

Japan’s iSpace were the most recent company to attempt a lunar lading in April this year, but failed as the Hakuto lander ran out of fuel while trying to descend. Aboard the vehicle was the UAE’s first lunar rover, named Rashid. Not deterred by this, the growing space nation is now preparing to send its second rover, Rashid-2, sometime in 2024, although they have yet to announce a launch partner.

Nevertheless, we are witnessing a turning point for the lunar economy, with the next year set to see more lunar missions. A number of these will be part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services programme, which includes missions from Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines and Firefly Aerospace. iSpace will also look to carry out another attempt, while Artemis-II will send astronauts on a trajectory around the Moon and back.

Appropriating lunar resources and building a legal space framework

With increasing commercial activity on the Moon comes a number of questions regarding the legality of it. For example, the iSpace mission was due to carry out the first commercial transaction on the Moon, in collecting a sample of lunar regolith and “selling” it to NASA. However, UN space law, namely the Outer Space Treaty, states that outer space “is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty”.

However, is appropriating resources technically the same as appropriating territory? Furthermore, how can the law be interpreted to govern the actions of private entities, as appose to state entities?

Speaking to CURIOS magazine in August, space lawyer, Michelle Hanlon, discussed some of these issues. Regarding Article 2, which covers issues relating to territorial claims, she argued that “…you cannot claim territory by means of sovereignty, or any other means, but it doesn't say that just a human individual can’t.” Would this then mean that commercial entities are free to appropriate resources and lunar territory?

However, the OST also states that national governments are responsible for the actions their commercial space entities. Therefore, if nations are obliged to act in accordance with international space law, can they legally and knowingly allow their commercial sector to simply start acting against those laws?

The issue is still ambiguous and underdeveloped. Furthermore, the pace of innovation is by far outpacing lawmaking. There are efforts to build some kind of regulatory framework, such as the US-led Artemis Accords and the Chinese-led International Lunar Research Station project (the former received their 31st member this week, the Netherlands.)

However, while these frameworks claim to act in accordance with the OST, neither effort is likely to bring together the space superpowers of the US, China and Russia. However, all three are signatories of the OST.

For Hanlon, the answer may lie in developing what we have, as she went on to say that “I love the Outer Space Treaty, it's a wonderful document, but it has a lot of gaps, and we really need to start thinking about filling those gaps.”

Private sectors to boost new space nations

The busy year of commercial lunar activity reflects the space industry as a whole, with states and agencies reaching out more and more to their private sectors.

This week, Indian launch startup, Skyroot, raised and additional $27.5 million, shortly after another company, Agnikul Cosmos, completed a funding round. Skyroot carried out India’s first private rocket launch last year. India have been putting emphasis on their private sector, now with 190 space startup in the country, twice as many as the year previous.

Taiwan have also been looking to boost their efforts in space and this week opened their Taiwan International Assembly of Space Science, Technology, and Industry. President Tsai Ing-wen joined the opening event, stating that the recent launch of their domestically developed Triton satellite proves that Taiwan has the technological advantages making it capable to grow in the space sector. Moreover, the event is designed to bring together public and private sectors, while building the nations global reputation in space.

ESA have also been further reaching out to the private sector, now looking for innovative technology innovations for space transportation. Named “First!”, the programme aims “…to identify innovative and promising technology disruptors with high commercial interest from both new and legacy industry players”, according to their website.

This follows similar ESA initiates (such as Boost!) whereby they have looked to stimulate their native commercial launch industry.

Soyuz spacecraft (Adobe)

Russia aims for satellite growth and space station launch

Russia is considered the founder of the space industry, but have been witnessing a steady decline, same argue since the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. The fallout from the Ukraine crisis means they have lost virtually all cooperation with the West on space projects and are now looking elsewhere for new partners.

In September, North Korean leader, Kim Jong-Un, visited Russia with Vladimir Putin taking him on a tour of Russian space facilities. It is widely believed that Russia will help North Korea develop its space technology. In return Russia would look to receive munitions and reports this week state that they have received over 1 million North Korean artillery shells.

The Russian president has also emphasised the need to develop accessible space services in partnership with BRICS nations, saying that "Today, the markets of Asia, Africa, and Latin America are developing more and more actively. Our partners from the CIS, EAEC, SCO, BRICS and other associations also have large-scale socio-economic plans. They are ready to form new segments of the economy (such as space) and increase their technological potential.”

Russia are also building on plans for their own orbital space station, with Putin also announcing last Thursday that the first segment of the ROSS station will be launched in 2027. The International Space Station (ISS), the last area where Russia still cooperates with the US and the West, will be retired by 2030 and nations and the private sector are scrambling to develop replacements.

Putin has also questioned Russia’s native satellite industry, demanding the Roscosmos reduce the cost of satellite production. Head of Roscosmos, Yuri Borisov, has stated that they only capacity to build “a few dozen satellites per year”, while speaking with a state news channel. In contrast, the US has the ability to produce around 3000 per year. Putin has ordered that new plans be put in place by July, 2024.

Russia may be facing strains caused by the ongoing war in Ukraine, but they do have the legacy and space heritage. Perhaps through forging new partnership, or also leveraging its own private sector, they could once again be a growing space nation.

Our future in space

Illustration of Blue Origin's Blue Moon Lander (Blue Origin)

03 November 2023

ESA Finally Commits to Join Lunar Economy, Blue Origin Unveils Lunar Lander, Commercial Moon Race Slated for January - Space News Roundup

With an increasing number of public and private missions heading to the Moon, we are witnessing the birth of the new lunar economy. The head of the European Space Agency this week expressed the need for the continent not to “miss the train”. Joseph Aschbacher commented on the European plan for a lunar base, insisting “it will happen”, and that in Europe there are “a lot” of companies seeing the potential on the Moon, hinting that the private sector will have a leading role to play.

He did admit that the European space budget may need to be increased in order to achieve a crewed landing on the Moon, but with the necessary resources they may achieve this sometime in the next decade.

Moreover, he expressed the urgency of the situation, outlining that this is time time to act, insisting that Europe cannot afford to miss out on such opportunities, as it has done before. “If we don’t do it, then exactly the same will happen as happened in chips, IT or other domains where Europe [has] not invested” he said.

Commercial entities are already pressing ahead with their plans on capitalising the new lunar economy, as seen through companies such as Qosmosys, who recently competed a $100 million funding towards their lunar exploration project. The Singapore-based company aim to use their own ZeusX spacecraft to develop infrastructure in space and prioritise “the commercial and financial potential of the Moon economy”, with a particular focus on the extraction of minerals such as Helium-3.

Sierra Space CEO, Tom Vice, once said that there is an industrial revolution going on “250 miles above our heads.” This is certainly true, witnessed through the growing number of commercial entities driving the industry forwards, building a rapidly growing infrastructure in-orbit. But now we are looking beyond only Earth orbit, and the next stop is the Moon.

Founder of Scout Ventures, Brad Harrison, summed this up well when recently while commenting on their funding efforts for Lonestar Data Holdings, saying that they believe that the lunar economy is “the next whitespace in the New Space Economy.”

Intuitive Machines delay lunar launch, setting up possibility of commercial Moon race

We’re set to see a flurry of activity on the Moon, beginning with commercial companies Intuitive Machines (US) and Astrobotic (US). The former were initially looking to launch this month but have now delayed the mission until January, while Astrobotc have a launch window opening on Christmas Eve.

This opens up the possibility of a commercial Moon race, similar to that between India and Russia earlier this year. While Astrobotic may launch sooner, they are launching on a new rocket, the ULA Vulcan, perhaps making it more prone to technical delays. Furthermore, they take a slightly longer journey to the surface, around 30 days, compared to Intuitive Machines who will take around 7 days.

Blue Origin have also been making moves towards the development of their own commercial lander, named “Blue Moon”. This week the company released images of its prototype of the Blue Moon Mark 1 lander. It will be capable carrying three metric tons to the lunar surface, with a Mark 2 version due to carry crew the surface for the first time as part of the Artemis programme, currently set for 2029. Earlier Artemis missions will use a modified version of SpaceX’s Starship for the landing.

Japan’s iSpace were the most recent company to attempt a lunar lading in April this year, but failed as the Hakuto lander ran out of fuel while trying to descend. Aboard the vehicle was the UAE’s first lunar rover, named Rashid. Not deterred by this, the growing space nation is now preparing to send its second rover, Rashid-2, sometime in 2024, although they have yet to announce a launch partner.

Nevertheless, we are witnessing a turning point for the lunar economy, with the next year set to see more lunar missions. A number of these will be part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services programme, which includes missions from Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines and Firefly Aerospace. iSpace will also look to carry out another attempt, while Artemis-II will send astronauts on a trajectory around the Moon and back.

Appropriating lunar resources and building a legal space framework

With increasing commercial activity on the Moon comes a number of questions regarding the legality of it. For example, the iSpace mission was due to carry out the first commercial transaction on the Moon, in collecting a sample of lunar regolith and “selling” it to NASA. However, UN space law, namely the Outer Space Treaty, states that outer space “is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty”.

However, is appropriating resources technically the same as appropriating territory? Furthermore, how can the law be interpreted to govern the actions of private entities, as appose to state entities?

Speaking to CURIOS magazine in August, space lawyer, Michelle Hanlon, discussed some of these issues. Regarding Article 2, which covers issues relating to territorial claims, she argued that “…you cannot claim territory by means of sovereignty, or any other means, but it doesn't say that just a human individual can’t.” Would this then mean that commercial entities are free to appropriate resources and lunar territory?

However, the OST also states that national governments are responsible for the actions their commercial space entities. Therefore, if nations are obliged to act in accordance with international space law, can they legally and knowingly allow their commercial sector to simply start acting against those laws?

The issue is still ambiguous and underdeveloped. Furthermore, the pace of innovation is by far outpacing lawmaking. There are efforts to build some kind of regulatory framework, such as the US-led Artemis Accords and the Chinese-led International Lunar Research Station project (the former received their 31st member this week, the Netherlands.)

However, while these frameworks claim to act in accordance with the OST, neither effort is likely to bring together the space superpowers of the US, China and Russia. However, all three are signatories of the OST.

For Hanlon, the answer may lie in developing what we have, as she went on to say that “I love the Outer Space Treaty, it's a wonderful document, but it has a lot of gaps, and we really need to start thinking about filling those gaps.”

Private sectors to boost new space nations

The busy year of commercial lunar activity reflects the space industry as a whole, with states and agencies reaching out more and more to their private sectors.

This week, Indian launch startup, Skyroot, raised and additional $27.5 million, shortly after another company, Agnikul Cosmos, completed a funding round. Skyroot carried out India’s first private rocket launch last year. India have been putting emphasis on their private sector, now with 190 space startup in the country, twice as many as the year previous.

Taiwan have also been looking to boost their efforts in space and this week opened their Taiwan International Assembly of Space Science, Technology, and Industry. President Tsai Ing-wen joined the opening event, stating that the recent launch of their domestically developed Triton satellite proves that Taiwan has the technological advantages making it capable to grow in the space sector. Moreover, the event is designed to bring together public and private sectors, while building the nations global reputation in space.

ESA have also been further reaching out to the private sector, now looking for innovative technology innovations for space transportation. Named “First!”, the programme aims “…to identify innovative and promising technology disruptors with high commercial interest from both new and legacy industry players”, according to their website.

This follows similar ESA initiates (such as Boost!) whereby they have looked to stimulate their native commercial launch industry.

Soyuz spacecraft (Adobe)

Russia aims for satellite growth and space station launch

Russia is considered the founder of the space industry, but have been witnessing a steady decline, same argue since the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. The fallout from the Ukraine crisis means they have lost virtually all cooperation with the West on space projects and are now looking elsewhere for new partners.

In September, North Korean leader, Kim Jong-Un, visited Russia with Vladimir Putin taking him on a tour of Russian space facilities. It is widely believed that Russia will help North Korea develop its space technology. In return Russia would look to receive munitions and reports this week state that they have received over 1 million North Korean artillery shells.

The Russian president has also emphasised the need to develop accessible space services in partnership with BRICS nations, saying that "Today, the markets of Asia, Africa, and Latin America are developing more and more actively. Our partners from the CIS, EAEC, SCO, BRICS and other associations also have large-scale socio-economic plans. They are ready to form new segments of the economy (such as space) and increase their technological potential.”

Russia are also building on plans for their own orbital space station, with Putin also announcing last Thursday that the first segment of the ROSS station will be launched in 2027. The International Space Station (ISS), the last area where Russia still cooperates with the US and the West, will be retired by 2030 and nations and the private sector are scrambling to develop replacements.

Putin has also questioned Russia’s native satellite industry, demanding the Roscosmos reduce the cost of satellite production. Head of Roscosmos, Yuri Borisov, has stated that they only capacity to build “a few dozen satellites per year”, while speaking with a state news channel. In contrast, the US has the ability to produce around 3000 per year. Putin has ordered that new plans be put in place by July, 2024.

Russia may be facing strains caused by the ongoing war in Ukraine, but they do have the legacy and space heritage. Perhaps through forging new partnership, or also leveraging its own private sector, they could once again be a growing space nation.

Share this article

03 November 2023

ESA Finally Commits to Join Lunar Economy, Blue Origin Unveils Lunar Lander, Commercial Moon Race Slated for January - Space News Roundup

Illustration of Blue Origin's Blue Moon Lander (Blue Origin)

With an increasing number of public and private missions heading to the Moon, we are witnessing the birth of the new lunar economy. The head of the European Space Agency this week expressed the need for the continent not to “miss the train”. Joseph Aschbacher commented on the European plan for a lunar base, insisting “it will happen”, and that in Europe there are “a lot” of companies seeing the potential on the Moon, hinting that the private sector will have a leading role to play.

He did admit that the European space budget may need to be increased in order to achieve a crewed landing on the Moon, but with the necessary resources they may achieve this sometime in the next decade.

Moreover, he expressed the urgency of the situation, outlining that this is time time to act, insisting that Europe cannot afford to miss out on such opportunities, as it has done before. “If we don’t do it, then exactly the same will happen as happened in chips, IT or other domains where Europe [has] not invested” he said.

Commercial entities are already pressing ahead with their plans on capitalising the new lunar economy, as seen through companies such as Qosmosys, who recently competed a $100 million funding towards their lunar exploration project. The Singapore-based company aim to use their own ZeusX spacecraft to develop infrastructure in space and prioritise “the commercial and financial potential of the Moon economy”, with a particular focus on the extraction of minerals such as Helium-3.

Sierra Space CEO, Tom Vice, once said that there is an industrial revolution going on “250 miles above our heads.” This is certainly true, witnessed through the growing number of commercial entities driving the industry forwards, building a rapidly growing infrastructure in-orbit. But now we are looking beyond only Earth orbit, and the next stop is the Moon.

Founder of Scout Ventures, Brad Harrison, summed this up well when recently while commenting on their funding efforts for Lonestar Data Holdings, saying that they believe that the lunar economy is “the next whitespace in the New Space Economy.”

Intuitive Machines delay lunar launch, setting up possibility of commercial Moon race

We’re set to see a flurry of activity on the Moon, beginning with commercial companies Intuitive Machines (US) and Astrobotic (US). The former were initially looking to launch this month but have now delayed the mission until January, while Astrobotc have a launch window opening on Christmas Eve.

This opens up the possibility of a commercial Moon race, similar to that between India and Russia earlier this year. While Astrobotic may launch sooner, they are launching on a new rocket, the ULA Vulcan, perhaps making it more prone to technical delays. Furthermore, they take a slightly longer journey to the surface, around 30 days, compared to Intuitive Machines who will take around 7 days.

Blue Origin have also been making moves towards the development of their own commercial lander, named “Blue Moon”. This week the company released images of its prototype of the Blue Moon Mark 1 lander. It will be capable carrying three metric tons to the lunar surface, with a Mark 2 version due to carry crew the surface for the first time as part of the Artemis programme, currently set for 2029. Earlier Artemis missions will use a modified version of SpaceX’s Starship for the landing.

Japan’s iSpace were the most recent company to attempt a lunar lading in April this year, but failed as the Hakuto lander ran out of fuel while trying to descend. Aboard the vehicle was the UAE’s first lunar rover, named Rashid. Not deterred by this, the growing space nation is now preparing to send its second rover, Rashid-2, sometime in 2024, although they have yet to announce a launch partner.

Nevertheless, we are witnessing a turning point for the lunar economy, with the next year set to see more lunar missions. A number of these will be part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services programme, which includes missions from Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines and Firefly Aerospace. iSpace will also look to carry out another attempt, while Artemis-II will send astronauts on a trajectory around the Moon and back.

Appropriating lunar resources and building a legal space framework

With increasing commercial activity on the Moon comes a number of questions regarding the legality of it. For example, the iSpace mission was due to carry out the first commercial transaction on the Moon, in collecting a sample of lunar regolith and “selling” it to NASA. However, UN space law, namely the Outer Space Treaty, states that outer space “is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty”.

However, is appropriating resources technically the same as appropriating territory? Furthermore, how can the law be interpreted to govern the actions of private entities, as appose to state entities?

Speaking to CURIOS magazine in August, space lawyer, Michelle Hanlon, discussed some of these issues. Regarding Article 2, which covers issues relating to territorial claims, she argued that “…you cannot claim territory by means of sovereignty, or any other means, but it doesn't say that just a human individual can’t.” Would this then mean that commercial entities are free to appropriate resources and lunar territory?

However, the OST also states that national governments are responsible for the actions their commercial space entities. Therefore, if nations are obliged to act in accordance with international space law, can they legally and knowingly allow their commercial sector to simply start acting against those laws?

The issue is still ambiguous and underdeveloped. Furthermore, the pace of innovation is by far outpacing lawmaking. There are efforts to build some kind of regulatory framework, such as the US-led Artemis Accords and the Chinese-led International Lunar Research Station project (the former received their 31st member this week, the Netherlands.)

However, while these frameworks claim to act in accordance with the OST, neither effort is likely to bring together the space superpowers of the US, China and Russia. However, all three are signatories of the OST.

For Hanlon, the answer may lie in developing what we have, as she went on to say that “I love the Outer Space Treaty, it's a wonderful document, but it has a lot of gaps, and we really need to start thinking about filling those gaps.”

Private sectors to boost new space nations

The busy year of commercial lunar activity reflects the space industry as a whole, with states and agencies reaching out more and more to their private sectors.

This week, Indian launch startup, Skyroot, raised and additional $27.5 million, shortly after another company, Agnikul Cosmos, completed a funding round. Skyroot carried out India’s first private rocket launch last year. India have been putting emphasis on their private sector, now with 190 space startup in the country, twice as many as the year previous.

Taiwan have also been looking to boost their efforts in space and this week opened their Taiwan International Assembly of Space Science, Technology, and Industry. President Tsai Ing-wen joined the opening event, stating that the recent launch of their domestically developed Triton satellite proves that Taiwan has the technological advantages making it capable to grow in the space sector. Moreover, the event is designed to bring together public and private sectors, while building the nations global reputation in space.

ESA have also been further reaching out to the private sector, now looking for innovative technology innovations for space transportation. Named “First!”, the programme aims “…to identify innovative and promising technology disruptors with high commercial interest from both new and legacy industry players”, according to their website.

This follows similar ESA initiates (such as Boost!) whereby they have looked to stimulate their native commercial launch industry.

Soyuz spacecraft (Adobe)

Russia aims for satellite growth and space station launch

Russia is considered the founder of the space industry, but have been witnessing a steady decline, same argue since the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. The fallout from the Ukraine crisis means they have lost virtually all cooperation with the West on space projects and are now looking elsewhere for new partners.

In September, North Korean leader, Kim Jong-Un, visited Russia with Vladimir Putin taking him on a tour of Russian space facilities. It is widely believed that Russia will help North Korea develop its space technology. In return Russia would look to receive munitions and reports this week state that they have received over 1 million North Korean artillery shells.

The Russian president has also emphasised the need to develop accessible space services in partnership with BRICS nations, saying that "Today, the markets of Asia, Africa, and Latin America are developing more and more actively. Our partners from the CIS, EAEC, SCO, BRICS and other associations also have large-scale socio-economic plans. They are ready to form new segments of the economy (such as space) and increase their technological potential.”

Russia are also building on plans for their own orbital space station, with Putin also announcing last Thursday that the first segment of the ROSS station will be launched in 2027. The International Space Station (ISS), the last area where Russia still cooperates with the US and the West, will be retired by 2030 and nations and the private sector are scrambling to develop replacements.

Putin has also questioned Russia’s native satellite industry, demanding the Roscosmos reduce the cost of satellite production. Head of Roscosmos, Yuri Borisov, has stated that they only capacity to build “a few dozen satellites per year”, while speaking with a state news channel. In contrast, the US has the ability to produce around 3000 per year. Putin has ordered that new plans be put in place by July, 2024.

Russia may be facing strains caused by the ongoing war in Ukraine, but they do have the legacy and space heritage. Perhaps through forging new partnership, or also leveraging its own private sector, they could once again be a growing space nation.

Share this article

External Links

This Week

*News articles posted here are not property of ANASDA GmbH and belong to their respected owners. Postings here are external links only.