28 Nov - 2 December 2022

New Space is growing exponentially, and we must work together to ensure a peaceful future

After Artemis launch, Mars doesn't seem as far away (Image: Adobe)

Determination to reap the rewards of new space in increasing throughout the world. Last week we witnessed how Europe and ESA have a renewed focus to become non-dependant in space, particularly in relation to launch capabilities. This week we have learnt about South Korea, and their long term goals in space. We’ve have already seen the successful launch of their Danuri lunar orbiter, surveying the moon for water, uranium, helium-3, silicon and aluminium.

President Yoon Suk-yeol revealed plans that include; developing engines that can send a rocket to the moon in the next five years, begin lunar mining by 2032 and land on Mars by 2045. It was announced how they will utilise the power of the private sector in order to achieve these goals, the president stating that “we will transfer space technologies owned by public agencies to the private sector and organize a funding program to develop world-leading private space companies.”

Private sector innovation has been the vessel which is taking us into New Space, and this week, an announcement from UK startup, MagDrive, have revealed a potentially new and disruptive technology. They claim that their propulsion system, MagDrive Nano, is ten times more efficient than the thrust in existing systems. They expect the first test of the engine in the coming weeks.

Another potentially revolutionary technology is that of smartphone-satellite connectivity, with Apple being the first to announce their new “SOS” function on the new iPhone. This tech would allow for users to remain connected, even when away from the terrestrial grid. Other satellite and network providers have recently followed suit, announcing similar proposals. The most recent to declare their plans are UK company, Bullit. Richard Wharton, co-founder, says that the phone will enable to connect to satellites from different operators. Should this trend continue, and this type of connectivity becomes a default feature, there could be a sizeable impact on the industry as a whole, from satellite production and demand for launches.

Our success will always rely on cooperation

New Space has the promise to provide economic and industrial stimulus, in otherwise uncertain times. Satellite-mobile connectivity is just one of these areas, that will also owe its success to cooperation. Nations and businesses are proving that working together can create opportunities for growth and development, and another of example of this came this week, with the announcement that South Korea and Luxembourg will look to strengthen their ties in numerous areas, including space.

Furthermore, following the announcement of ESA’s long-term goals last week, it has been revealed that they will look to work together with NASA on their revived ExoMars programme. Due to launch in 2028, ESA head, Josef Aschbacher, anticipates that the US may provide technology such as a launcher and braking engine. The project will, however, have renewed focus on primarily European components.

NASA have this week awarded a contract ICON, located in Austin, to develop construction technologies that could one day build infrastructure on the surface of the moon, such as launchpads and habitats. Niki Werkheiser, director of technology maturation in NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate (STMD), stated that "pushing this development forward with our commercial partners will create the capabilities we need for future missions.” Partnerships with the private sector continue to be vital for our futures in space.

Working together will also be vital for new space nations, and this week it was announced that the UNOOSA will be working with the Kenya Space Agency under the “Space Law for New Space Actors” project. The project gives UN Member States ad-hoc capacity-building to draft national space legislation and/or national space policies in line with international space law, assisting new space nations enter the sector.

Another cause for working together is that of striving for peace and safety in space. This week France have officially joined the US-led moratorium of banning ASAT testing in orbit. They follow in the in the footsteps of the UK, Australia, Germany and others, who have made similar commitments. Whilst this can be seen as a positive step, could it also cause antagonism with others? When a draft resolution at the UN, pledging not to conduct destructive direct-ascent ASAT tests, it was approved on a 154-8 vote. Two nations who voted against, were China and Russia. What aspect of the motion deters them from joining? Do they both see the US-led motion as a form of political alliance? If so, how will it ever be possible to create unanimity in our quest for peace in New Space?

Are "space blocs" in a race to launch into space? (Image: Adobe)

Whilst we grow closer, we risk growing apart - growth of space “blocs”

Working together will be essential in order to bring about common goals, through sharing technology and building bridges that ensure peace in space. However, is there a risk that whilst new alliances form, they will grow increasingly competitive again each other? The Artemis Accords continues to gather new members, as does the US ASAT moratorium, but how likely is it that China and/or Russia will ever sign-up to them? Furthermore, will the pursuit of sovereign space technology even lead to old allies moving gently apart?

Ann Buel, a former EU officer, highlighted this week in an opinion editorial, the growth of the rival blocs of the US-led Artemis Accords, and the Sino-Russian alliance on their ILRS project. She states that “Although being open, these blocs do not collaborate to accomplish similar missions on the Moon, which indicates that strategic interests and rivalries on the ground have been transposed to space.” (chinadaily.com.cn, 2022). Earthly politics seem to have seeped into the space domain, binging about the reality of new, grand alliances, competing against each other.

US Space Command exemplified their rivalry with China this week, by highlighting the importance of their relationship with Australia in space, with General M. Armago saying that Australia’s geographical position and capabilities represent a “pot of a gold at the end of the rainbow” for the two countries’ interests in space defence (spacenews.com, 2022). Furthermore, US Gen. James Dickinson, head of U.S. Space Command, has supported the idea of using commercial partners to support US responsive launch capabilities, in order to keep the lead over China. There’s no doubt about the growing rivalry between the two giants in space, but are they the only two nations aspiring to establish their own space blocs?

Ann Beul, in her article, also pointed out that the emergence of space blocs is nothing new, and in fact, that ESA is perhaps the first bloc to have formed in the 1975. As part of their quest for launch non-dependance, this week Arianespace have been announced as the company to launch five Copernicus Earth observation spacecraft on Vega C rockets between 2024 and 2026. Without stating the cost, Ariane chief executive, Stéphane Israël, stated that the deal was competitive with American providers. This could be a significant step for Ariane, but also for Europe’s quest to stand on their own two feet, and maybe a somewhat gentle step away from reliance on US launch providers. Should Europe look to forge its own path, what policies could form part of their agenda in New Space? Could they provide an alternative to the Artemis Accords and the ILRS?

There’s no doubt about it, New Space is becoming a higher priority for nations throughout the world. Cooperation is going to be key to our success, in achieving our goals and maintaining peace. However, there is also a risk that apposing alliances, or rival space blocs, will become increasingly competitive, and risk a peaceful future in space. Whilst geopolitics seems to make it increasingly difficult for adversaries to work together, for now door must be left open, for our success should be the benefit of all humankind.

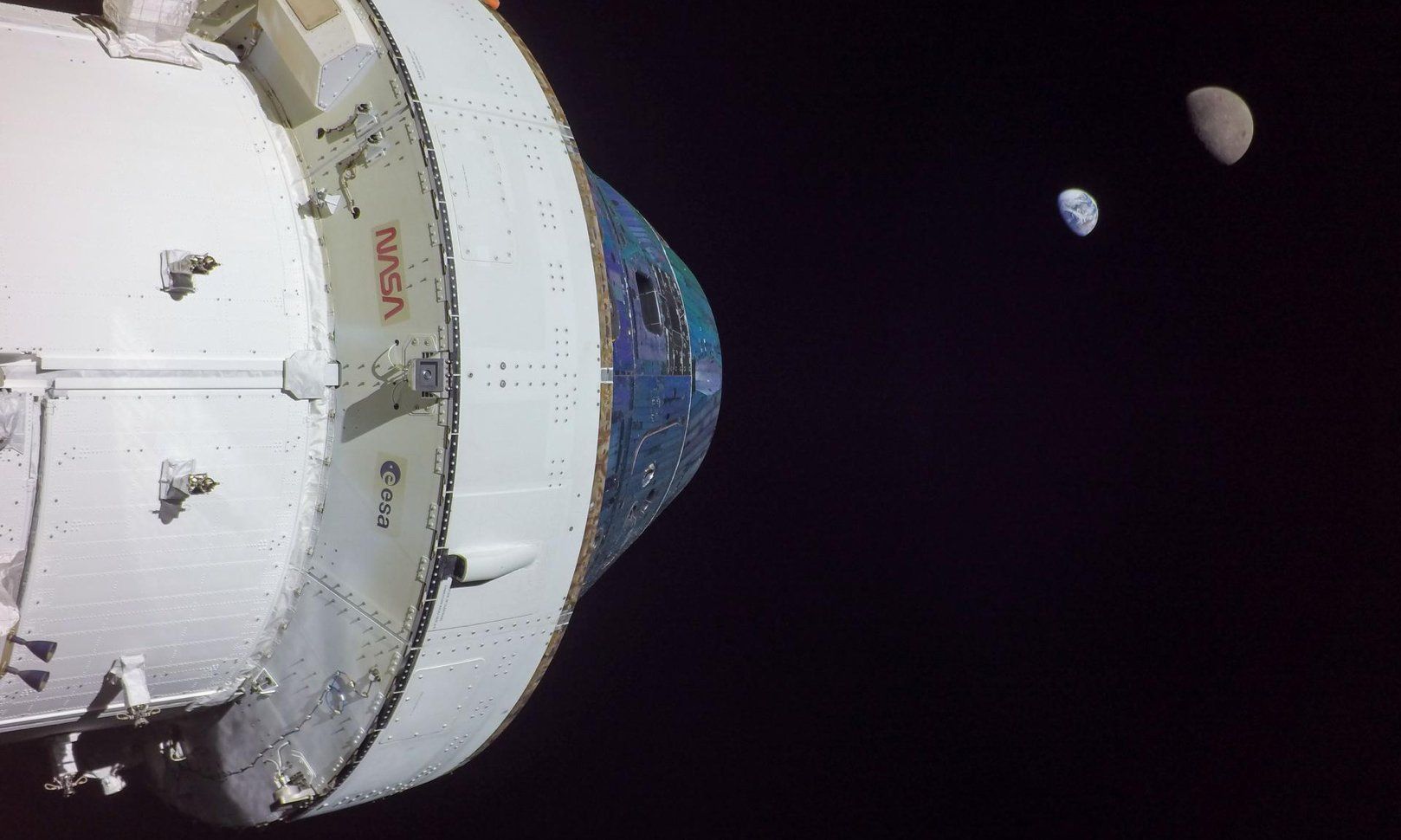

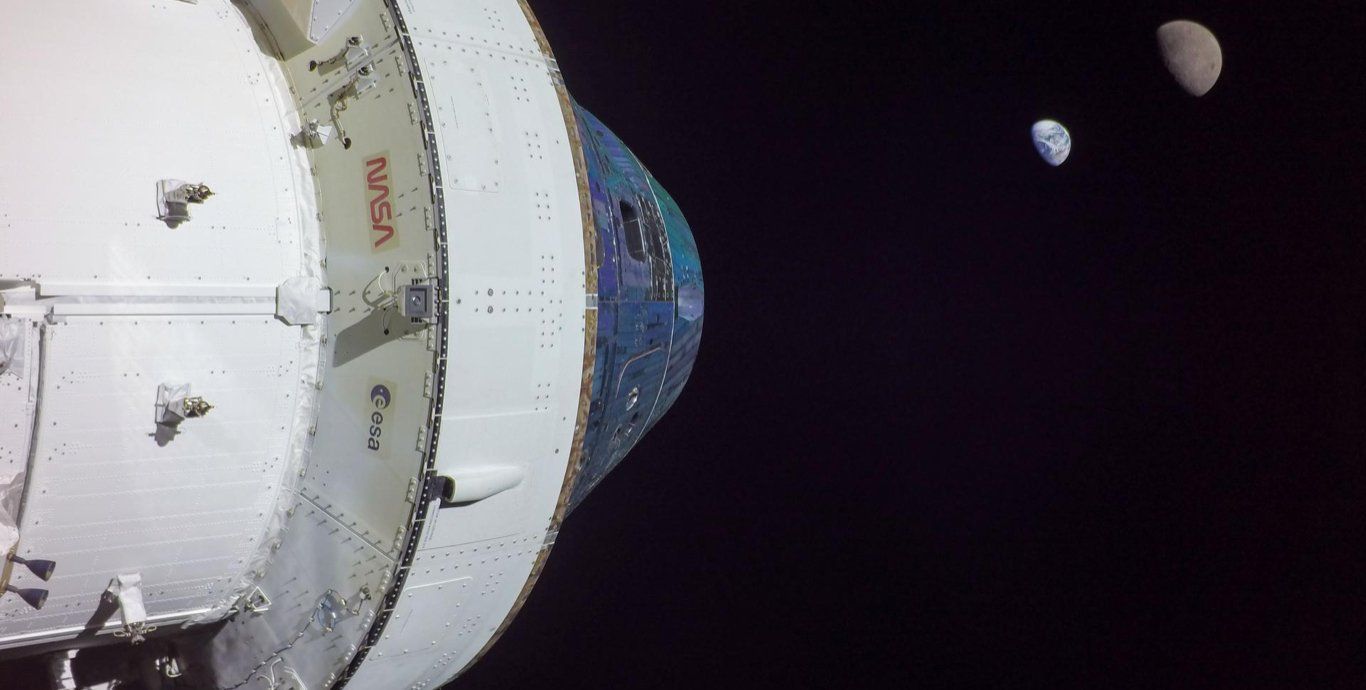

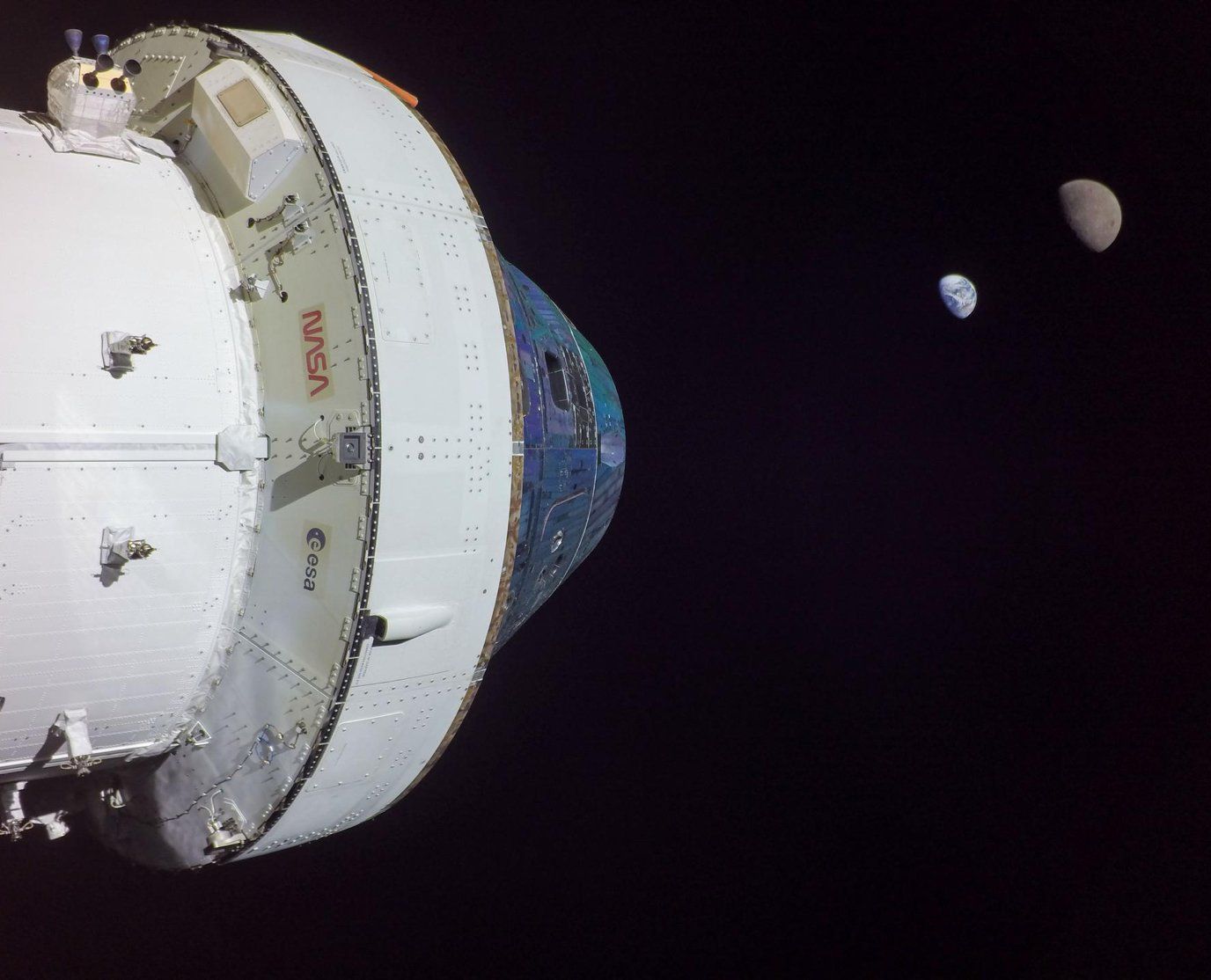

Orion further than any other human-proof spacecraft (Image: NASA)

A peaceful and successful future in space can only become reality by working together

At lot can be said about working together towards common goals, and space has been a fine example of that. Cooperation on ISS has been a long-term success, even whilst relations between adversaries are almost non-existent. This year we are also witnessing the birth of a number of other cooperative projects, which together, are building the foundations of New Space.

Artemis-1 is continuing its path around the moon, and will begin its journey back to Earth this week, expected to splash-down on the 11th December. The mission has continued to be success, and an example of cooperation. The Orion spacecraft has travelled around the moon with the support of the European Service Module (ESM), provided by ESA. Indeed, the Artemis project brings together nations throughout the world, with the US-led Artemis Accords building a legal framework for the new space economy.

Furthermore, and despite some setbacks, soon iSpace look set to send the first ever commercial lander mission to the moon, carrying a number of payloads including lunar rovers for both the UAE and Japan. The mission will also mark the beginning of the commercialisation of the moon.

Partnerships and cooperative alliances can bring about remarkable innovation, and realties that were, until not long ago, closer to fiction. However, is there a threat that these partnerships could turn into rival blocs, and encourage aggressive competition in space? Is there a way in which rival alliances could learn how to work together for common goals?

External Links

This Week

*News articles posted here are not property of ANASDA GmbH and belong to their respected owners. Postings here are external links only.

Our future in space

After Artemis launch, Mars doesn't seem as far away (Image: Adobe)

28 Nov - 02 December 2022

New Space is growing exponentially, therefore we must work together to ensure peaceful future

Determination to reap the rewards of new space in increasing throughout the world. Last week we witnessed how Europe and ESA have a renewed focus to become non-dependant in space, particularly in relation to launch capabilities. This week we have learnt about South Korea, and their long term goals in space. We’ve have already seen the successful launch of their Danuri lunar orbiter, surveying the moon for water, uranium, helium-3, silicon and aluminium.

President Yoon Suk-yeol revealed plans that include; developing engines that can send a rocket to the moon in the next five years, begin lunar mining by 2032 and land on Mars by 2045. It was announced how they will utilise the power of the private sector in order to achieve these goals, the president stating that “we will transfer space technologies owned by public agencies to the private sector and organize a funding program to develop world-leading private space companies.”

Private sector innovation has been the vessel which is taking us into New Space, and this week, an announcement from UK startup, MagDrive, have revealed a potentially new and disruptive technology. They claim that their propulsion system, MagDrive Nano, is ten times more efficient than the thrust in existing systems. They expect the first test of the engine in the coming weeks.

Another potentially revolutionary technology is that of smartphone-satellite connectivity, with Apple being the first to announce their new “SOS” function on the new iPhone. This tech would allow for users to remain connected, even when away from the terrestrial grid. Other satellite and network providers have recently followed suit, announcing similar proposals. The most recent to declare their plans are UK company, Bullit. Richard Wharton, co-founder, says that the phone will enable to connect to satellites from different operators. Should this trend continue, and this type of connectivity becomes a default feature, there could be a sizeable impact on the industry as a whole, from satellite production and demand for launches.

Our success will always rely on cooperation

New Space has the promise to provide economic and industrial stimulus, in otherwise uncertain times. Satellite-mobile connectivity is just one of these areas, that will also owe its success to cooperation. Nations and businesses are proving that working together can create opportunities for growth and development, and another of example of this came this week, with the announcement that South Korea and Luxembourg will look to strengthen their ties in numerous areas, including space.

Furthermore, following the announcement of ESA’s long-term goals last week, it has been revealed that they will look to work together with NASA on their revived ExoMars programme. Due to launch in 2028, ESA head, Josef Aschbacher, anticipates that the US may provide technology such as a launcher and braking engine. The project will, however, have renewed focus on primarily European components.

NASA have this week awarded a contract ICON, located in Austin, to develop construction technologies that could one day build infrastructure on the surface of the moon, such as launchpads and habitats. Niki Werkheiser, director of technology maturation in NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate (STMD), stated that "pushing this development forward with our commercial partners will create the capabilities we need for future missions.” Partnerships with the private sector continue to be vital for our futures in space.

Working together will also be vital for new space nations, and this week it was announced that the UNOOSA will be working with the Kenya Space Agency under the “Space Law for New Space Actors” project. The project gives UN Member States ad-hoc capacity-building to draft national space legislation and/or national space policies in line with international space law, assisting new space nations enter the sector.

Another cause for working together is that of striving for peace and safety in space. This week France have officially joined the US-led moratorium of banning ASAT testing in orbit. They follow in the in the footsteps of the UK, Australia, Germany and others, who have made similar commitments. Whilst this can be seen as a positive step, could it also cause antagonism with others? When a draft resolution at the UN, pledging not to conduct destructive direct-ascent ASAT tests, it was approved on a 154-8 vote. Two nations who voted against, were China and Russia. What aspect of the motion deters them from joining? Do they both see the US-led motion as a form of political alliance? If so, how will it ever be possible to create unanimity in our quest for peace in New Space?

Are "space blocs" in a race to launch into space? (Image: Adobe)

Whilst we grow closer, we risk growing apart - growth of space “blocs”

Working together will be essential in order to bring about common goals, through sharing technology and building bridges that ensure peace in space. However, is there a risk that whilst new alliances form, they will grow increasingly competitive again each other? The Artemis Accords continues to gather new members, as does the US ASAT moratorium, but how likely is it that China and/or Russia will ever sign-up to them? Furthermore, will the pursuit of sovereign space technology even lead to old allies moving gently apart?

Ann Buel, a former EU officer, highlighted this week in an opinion editorial, the growth of the rival blocs of the US-led Artemis Accords, and the Sino-Russian alliance on their ILRS project. She states that “Although being open, these blocs do not collaborate to accomplish similar missions on the Moon, which indicates that strategic interests and rivalries on the ground have been transposed to space.” (chinadaily.com.cn, 2022). Earthly politics seem to have seeped into the space domain, binging about the reality of new, grand alliances, competing against each other.

US Space Command exemplified their rivalry with China this week, by highlighting the importance of their relationship with Australia in space, with General M. Armago saying that Australia’s geographical position and capabilities represent a “pot of a gold at the end of the rainbow” for the two countries’ interests in space defence (spacenews.com, 2022). Furthermore, US Gen. James Dickinson, head of U.S. Space Command, has supported the idea of using commercial partners to support US responsive launch capabilities, in order to keep the lead over China. There’s no doubt about the growing rivalry between the two giants in space, but are they the only two nations aspiring to establish their own space blocs?

Ann Beul, in her article, also pointed out that the emergence of space blocs is nothing new, and in fact, that ESA is perhaps the first bloc to have formed in the 1975. As part of their quest for launch non-dependance, this week Arianespace have been announced as the company to launch five Copernicus Earth observation spacecraft on Vega C rockets between 2024 and 2026. Without stating the cost, Ariane chief executive, Stéphane Israël, stated that the deal was competitive with American providers. This could be a significant step for Ariane, but also for Europe’s quest to stand on their own two feet, and maybe a somewhat gentle step away from reliance on US launch providers. Should Europe look to forge its own path, what policies could form part of their agenda in New Space? Could they provide an alternative to the Artemis Accords and the ILRS?

There’s no doubt about it, New Space is becoming a higher priority for nations throughout the world. Cooperation is going to be key to our success, in achieving our goals and maintaining peace. However, there is also a risk that apposing alliances, or rival space blocs, will become increasingly competitive, and risk a peaceful future in space. Whilst geopolitics seems to make it increasingly difficult for adversaries to work together, for now door must be left open, for our success should be the benefit of all humankind.

Orion further than any other human-proof spacecraft (Image: NASA)

A peaceful and successful future in space can only become reality by working together

At lot can be said about working together towards common goals, and space has been a fine example of that. Cooperation on ISS has been a long-term success, even whilst relations between adversaries are almost non-existent. This year we are also witnessing the birth of a number of other cooperative projects, which together, are building the foundations of New Space.

Artemis-1 is continuing its path around the moon, and will begin its journey back to Earth this week, expected to splash-down on the 11th December. The mission has continued to be success, and an example of cooperation. The Orion spacecraft has travelled around the moon with the support of the European Service Module (ESM), provided by ESA. Indeed, the Artemis project brings together nations throughout the world, with the US-led Artemis Accords building a legal framework for the new space economy.

Furthermore, and despite some setbacks, soon iSpace look set to send the first ever commercial lander mission to the moon, carrying a number of payloads including lunar rovers for both the UAE and Japan. The mission will also mark the beginning of the commercialisation of the moon.

Partnerships and cooperative alliances can bring about remarkable innovation, and realties that were, until not long ago, closer to fiction. However, is there a threat that these partnerships could turn into rival blocs, and encourage aggressive competition in space? Is there a way in which rival alliances could learn how to work together for common goals?

Share this article

External Links

This Week

*News articles posted here are not property of ANASDA GmbH and belong to their respected owners. Postings here are external links only.

28 Nov - 01 Dec 2022

New Space is growing exponentially, and we must work together to ensure a peaceful future

After Artemis launch, Mars doesn't seem as far away (Image: Adobe)

Determination to reap the rewards of new space in increasing throughout the world. Last week we witnessed how Europe and ESA have a renewed focus to become non-dependant in space, particularly in relation to launch capabilities. This week we have learnt about South Korea, and their long term goals in space. We’ve have already seen the successful launch of their Danuri lunar orbiter, surveying the moon for water, uranium, helium-3, silicon and aluminium.

President Yoon Suk-yeol revealed plans that include; developing engines that can send a rocket to the moon in the next five years, begin lunar mining by 2032 and land on Mars by 2045. It was announced how they will utilise the power of the private sector in order to achieve these goals, the president stating that “we will transfer space technologies owned by public agencies to the private sector and organize a funding program to develop world-leading private space companies.”

Private sector innovation has been the vessel which is taking us into New Space, and this week, an announcement from UK startup, MagDrive, have revealed a potentially new and disruptive technology. They claim that their propulsion system, MagDrive Nano, is ten times more efficient than the thrust in existing systems. They expect the first test of the engine in the coming weeks.

Another potentially revolutionary technology is that of smartphone-satellite connectivity, with Apple being the first to announce their new “SOS” function on the new iPhone. This tech would allow for users to remain connected, even when away from the terrestrial grid. Other satellite and network providers have recently followed suit, announcing similar proposals. The most recent to declare their plans are UK company, Bullit. Richard Wharton, co-founder, says that the phone will enable to connect to satellites from different operators. Should this trend continue, and this type of connectivity becomes a default feature, there could be a sizeable impact on the industry as a whole, from satellite production and demand for launches.

Our success will always rely on cooperation

New Space has the promise to provide economic and industrial stimulus, in otherwise uncertain times. Satellite-mobile connectivity is just one of these areas, that will also owe its success to cooperation. Nations and businesses are proving that working together can create opportunities for growth and development, and another of example of this came this week, with the announcement that South Korea and Luxembourg will look to strengthen their ties in numerous areas, including space.

Furthermore, following the announcement of ESA’s long-term goals last week, it has been revealed that they will look to work together with NASA on their revived ExoMars programme. Due to launch in 2028, ESA head, Josef Aschbacher, anticipates that the US may provide technology such as a launcher and braking engine. The project will, however, have renewed focus on primarily European components.

NASA have this week awarded a contract ICON, located in Austin, to develop construction technologies that could one day build infrastructure on the surface of the moon, such as launchpads and habitats. Niki Werkheiser, director of technology maturation in NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate (STMD), stated that "pushing this development forward with our commercial partners will create the capabilities we need for future missions.” Partnerships with the private sector continue to be vital for our futures in space.

Working together will also be vital for new space nations, and this week it was announced that the UNOOSA will be working with the Kenya Space Agency under the “Space Law for New Space Actors” project. The project gives UN Member States ad-hoc capacity-building to draft national space legislation and/or national space policies in line with international space law, assisting new space nations enter the sector.

Another cause for working together is that of striving for peace and safety in space. This week France have officially joined the US-led moratorium of banning ASAT testing in orbit. They follow in the in the footsteps of the UK, Australia, Germany and others, who have made similar commitments. Whilst this can be seen as a positive step, could it also cause antagonism with others? When a draft resolution at the UN, pledging not to conduct destructive direct-ascent ASAT tests, it was approved on a 154-8 vote. Two nations who voted against, were China and Russia. What aspect of the motion deters them from joining? Do they both see the US-led motion as a form of political alliance? If so, how will it ever be possible to create unanimity in our quest for peace in New Space?

Are "space blocs" in a race to launch into space (Image: Adobe)

Whilst we grow closer, we risk growing apart - growth of space “blocs”

Working together will be essential in order to bring about common goals, through sharing technology and building bridges that ensure peace in space. However, is there a risk that whilst new alliances form, they will grow increasingly competitive again each other? The Artemis Accords continues to gather new members, as does the US ASAT moratorium, but how likely is it that China and/or Russia will ever sign-up to them? Furthermore, will the pursuit of sovereign space technology even lead to old allies moving gently apart?

Ann Buel, a former EU officer, highlighted this week in an opinion editorial, the growth of the rival blocs of the US-led Artemis Accords, and the Sino-Russian alliance on their ILRS project. She states that “Although being open, these blocs do not collaborate to accomplish similar missions on the Moon, which indicates that strategic interests and rivalries on the ground have been transposed to space.” (chinadaily.com.cn, 2022). Earthly politics seem to have seeped into the space domain, binging about the reality of new, grand alliances, competing against each other.

US Space Command exemplified their rivalry with China this week, by highlighting the importance of their relationship with Australia in space, with General M. Armago saying that Australia’s geographical position and capabilities represent a “pot of a gold at the end of the rainbow” for the two countries’ interests in space defence (spacenews.com, 2022). Furthermore, US Gen. James Dickinson, head of U.S. Space Command, has supported the idea of using commercial partners to support US responsive launch capabilities, in order to keep the lead over China. There’s no doubt about the growing rivalry between the two giants in space, but are they the only two nations aspiring to establish their own space blocs?

Ann Beul, in her article, also pointed out that the emergence of space blocs is nothing new, and in fact, that ESA is perhaps the first bloc to have formed in the 1975. As part of their quest for launch non-dependance, this week Arianespace have been announced as the company to launch five Copernicus Earth observation spacecraft on Vega C rockets between 2024 and 2026. Without stating the cost, Ariane chief executive, Stéphane Israël, stated that the deal was competitive with American providers. This could be a significant step for Ariane, but also for Europe’s quest to stand on their own two feet, and maybe a somewhat gentle step away from reliance on US launch providers. Should Europe look to forge its own path, what policies could form part of their agenda in New Space? Could they provide an alternative to the Artemis Accords and the ILRS?

There’s no doubt about it, New Space is becoming a higher priority for nations throughout the world. Cooperation is going to be key to our success, in achieving our goals and maintaining peace. However, there is also a risk that apposing alliances, or rival space blocs, will become increasingly competitive, and risk a peaceful future in space. Whilst geopolitics seems to make it increasingly difficult for adversaries to work together, for now door must be left open, for our success should be the benefit of all humankind.

Orion spacecraft further than any other human-proof spacecraft (Image: NASA)

A peaceful and successful future in space can only become reality by working together

At lot can be said about working together towards common goals, and space has been a fine example of that. Cooperation on ISS has been a long-term success, even whilst relations between adversaries are almost non-existent. This year we are also witnessing the birth of a number of other cooperative projects, which together, are building the foundations of New Space.

Artemis-1 is continuing its path around the moon, and will begin its journey back to Earth this week, expected to splash-down on the 11th December. The mission has continued to be success, and an example of cooperation. The Orion spacecraft has travelled around the moon with the support of the European Service Module (ESM), provided by ESA. Indeed, the Artemis project brings together nations throughout the world, with the US-led Artemis Accords building a legal framework for the new space economy.

Furthermore, and despite some setbacks, soon iSpace look set to send the first ever commercial lander mission to the moon, carrying a number of payloads including lunar rovers for both the UAE and Japan. The mission will also mark the beginning of the commercialisation of the moon.

Partnerships and cooperative alliances can bring about remarkable innovation, and realties that were, until not long ago, closer to fiction. However, is there a threat that these partnerships could turn into rival blocs, and encourage aggressive competition in space? Is there a way in which rival alliances could learn how to work together for common goals?

Share this article

External Links

This Week

*News articles posted here are not property of ANASDA GmbH and belong to their respected owners. Postings here are external links only.