Define Our Future

22 March 2024

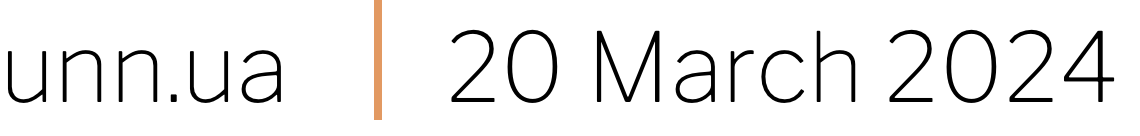

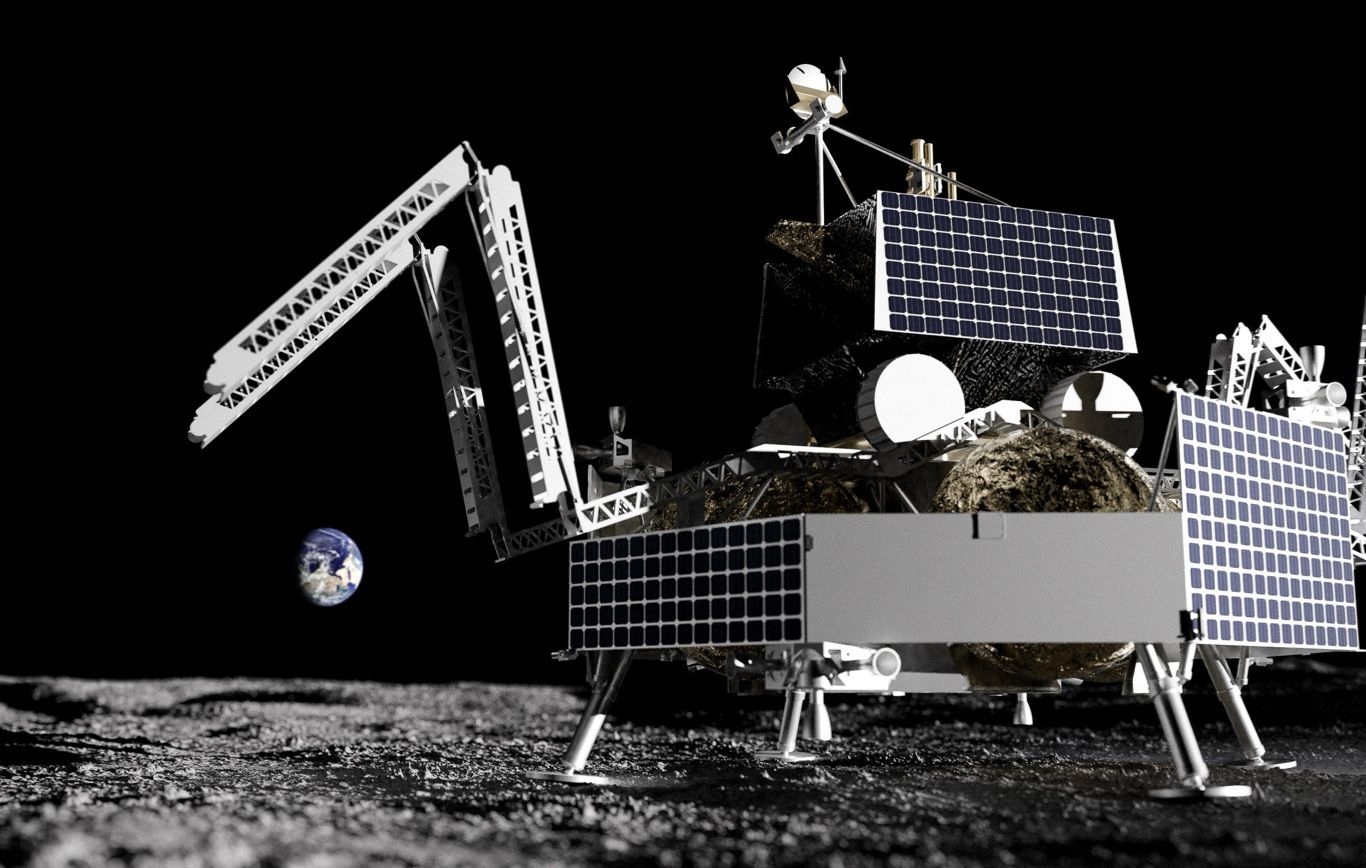

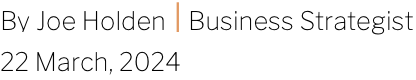

Illustration of Astrobotic Griffin lander (Astrobotic)

Determination appears to be growing in the space sector, to build on recent successes and demonstrate technologies which will support and build a new lunar infrastructure and economy. Only in recent weeks we have reported news regarding companies such as Interlune, who plan to extract and retrieve Helium-3, as well as Russian and Chinese plans to build a nuclear reactor on the Moon by the 2030s.

This week Japanese startup iSpace announced plans to produce the first hydrogen on the Moon, as part of their Hakuto-R second lunar landing attempt later this year. Japanese company Takasago Thermal Engineering handed over their water electrolyser and storage tank system to iSpace on Monday. Once on the Moon the electrolyser will use surface-water to generate hydrogen and oxygen, which in future has the potential to produce rocket fuel and sustain life on the Moon.

Furthermore, not to be deterred from their failed first lunar mission, US startup Astrobotic are preparing for their second landing attempt, possibly at the end of this year. The company recently described how they’ve gathered much useful data from their first mission in January, using their Peregrine lander. Although the mission ultimately did not reach the Moon, it did manage to power-up most of its payloads, with NASA saying that one of their payloads, the Linear Energy Transfer Spectrometer (LETS), worked perfectly the whole time.

NASA drill among Astrobotic payloads

Astrobotic is now working towards the launch of their larger lander, the Griffin Mission One. Among the payloads, NASA will send their Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER), which is seen as a significant opportunity to learn about the presence and distribution of water at the lunar south pole. VIPER will carry a number of tools and spectrometers, including the Regolith and Ice Drill for Exploring New Terrains (TRIDENT), tasked with digging-up soil from the beneath the surface, which will then be analysed regarding the presence of hydrogen.

Such missions will provide significant insights, which in-turn help to inform agencies and companies better about the next steps towards to construction of a lunar infrastructure and habitats. Locating and refining water is one of the most pressing challenges to overcome, and is also being explored by private companies, such as Starpath Robotics.

SpaceX Starlink launch (SpaceX)

SpaceX to build US defence satellites, Musk influence again questioned

There’s no doubt that SpaceX are the leading force in the space sector right now, ever-increasing their launch-rate, expanding their Starlink mega-constellation and building landing systems for crewed lunar landings.

They are now also developing Starshield, derived from the Starlink constellation, but provided to military and defence customers. Furthermore, it has this week been reported that the company is also developing a network of hundreds of spy satellites under a classified contract for the US National Reconnaissance Office, signed in 2021.

Not only does this show the increasingly important role that space is now playing in military and defence, but also demonstrates how the government and military is becoming more reliant on private space entities, especially SpaceX.

While services provided by SpaceX give the US an advantage against its rivals in the space domain, it also once again raises the question about the power and influence over political and geopolitical matters commanded by commercial entities and individuals such as Elon Musk.

Writing this week for the Washington Post, Max Boot gave a very critical opinion of the SpaceX CEO, saying that Musk “pursues his own foreign policy”, referring to when he stepped-in to prevent Starlink being used by Ukrainian forces to attack the Russian naval fleet, and also referred to recent news that members of Congress have accused SpaceX of turning-off Starshield in and around Taiwan.

Boot also correctly states that there isn’t really any alternative to SpaceX at the moment, and so agencies and governments are relying on them for launches and connectivity. For example, the EU has this week, out of necessity, signed a deal with SpaceX for satellite launches, as they currently lack their own independant access to orbit.

However, this is set to change, with a number of companies looking to carry out maiden launches and expand their services this year. In-light of Musk’s tendency to weigh-in on geopolitics and foreign policy, will agencies and other customers soon choose to either move away or diversify from SpaceX services?

It will though take time, innovation and effective strategies to compete with SpaceX. We are also yet to see the impact of a truly usable and servicing Starship, which could again drastically reduce launch costs and force competitors out of the market.

UN buildings in Vienna (Adobe)

Critical year for space policy amid rising tensions

Legislative and geopolitical challenges are on the rise in the space sector, with recent threats of space militarisation, and the void of international laws that sufficiently govern the age of New Space and the prospect of extracting and utilising space resources. In his recent book “Who Owns The Moon”, AC Grayling discusses the effectiveness of UN law, namely the Outer Space Treaty (OST) 1967, which binds nations to peaceful and globally beneficial aspirations for space, including preventing nuclear weapons and forbidding territorial acquisition.

However, he also makes the point that throughout the treaty it makes reference to these “aspirations”, and that they are so just that. He writes “US statements of aspirations are made in the full knowledge that the attempt to give them effect in the form of international treaties and binding international law carries no guarantee that they will be realised,” (Grayling, 2024).

He goes on to make reference to instances where UN and international law has in the past been simply resisted or reshaped, such as when the US renegotiated the UN Law of the Seas to allow for seabed mining, or when the Trump administration simply abandoned the 2012 Paris Climate Accords.

The necessity to address these issues perhaps comes at the most pressing time. The US has made recent allegations that Russia intends to launch nuclear powered weapon in space, while Russia has this week warned the US against using SpaceX for spying capabilities, saying that in such a scenario, commercial entities would “become a legitimate target for retaliatory measures, including military ones”.

Meanwhile, this week Ukraine has indicated its desire to join the EU Space Programme and build closer ties to ESA, a move which could spark reaction from the Putin regime and have wider impact on the Ukraine war, which is sometimes dubbed the “first commercial space war”.

Opinion: Space is hard, and so is peaceful space

National and commercial activities in space are sharply on the rise, with a growing lunar launch cadence, international plans to build lunar bases and projects directed at developing a new commercial lunar economy. This goes without mentioning the exponential growth of satellite numbers in orbit and the birth of a new, sophisticated orbital infrastructure.

With this growth will always come the need to develop new frameworks, in order to guarantee the mutual benefits of space, based on peaceful uses. AC Grayling does make a valid point regarding UN law and its aspirations, and that they can simply be abandoned at any time. We are also stepping into new territory, with only comparative history able to inform us about what future scenarios in space may look like.

However, efforts are at least currently being made from most sides at UN level. The US and Japan have this week have supported a UN Security Council resolution calling on all nations not to deploy or develop nuclear weapons in space. This month China submitted a paper to the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) outlining a proposal to work with the UN in regards to managing resource extraction in outer space, keeping in-line with the OST. Furthermore, in January, Russia also submitted a proposal to COPUOS, proposing that “space science and technology should be used for the peaceful exploration and use of outer space in the interest of maintaining international peace”.

Amongst the flurry of accusations and growth of new space actors, there may at least still be some efforts being made to build a lasting peace in outer space.

Define Our Future

(Adobe)

22 March 2024

iSpace and Astrobotic prep second lunar missions, SpaceX deepens influence in a pivotal year for space policy - Space News Roundup

Determination appears to be growing in the space sector, to build on recent successes and demonstrate technologies which will support and build a new lunar infrastructure and economy. Only in recent weeks we have reported news regarding companies such as Interlune, who plan to extract and retrieve Helium-3, as well as Russian and Chinese plans to build a nuclear reactor on the Moon by the 2030s.

This week Japanese startup iSpace announced plans to produce the first hydrogen on the Moon, as part of their Hakuto-R second lunar landing attempt later this year. Japanese company Takasago Thermal Engineering handed over their water electrolyser and storage tank system to iSpace on Monday. Once on the Moon the electrolyser will use surface-water to generate hydrogen and oxygen, which in future has the potential to produce rocket fuel and sustain life on the Moon.

Furthermore, not to be deterred from their failed first lunar mission, US startup Astrobotic are preparing for their second landing attempt, possibly at the end of this year. The company recently described how they’ve gathered much useful data from their first mission in January, using their Peregrine lander. Although the mission ultimately did not reach the Moon, it did manage to power-up most of its payloads, with NASA saying that one of their payloads, the Linear Energy Transfer Spectrometer (LETS), worked perfectly the whole time.

NASA drill among Astrobotic payloads

Astrobotic is now working towards the launch of their larger lander, the Griffin Mission One. Among the payloads, NASA will send their Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER), which is seen as a significant opportunity to learn about the presence and distribution of water at the lunar south pole. VIPER will carry a number of tools and spectrometers, including the Regolith and Ice Drill for Exploring New Terrains (TRIDENT), tasked with digging-up soil from the beneath the surface, which will then be analysed regarding the presence of hydrogen.

Such missions will provide significant insights, which in-turn help to inform agencies and companies better about the next steps towards to construction of a lunar infrastructure and habitats. Locating and refining water is one of the most pressing challenges to overcome, and is also being explored by private companies, such as Starpath Robotics.

SpaceX Starlink launch (SpaceX)

SpaceX to build US defence satellites, Musk influence again questioned

There’s no doubt that SpaceX are the leading force in the space sector right now, ever-increasing their launch-rate, expanding their Starlink mega-constellation and building landing systems for crewed lunar landings.

They are now also developing Starshield, derived from the Starlink constellation, but provided to military and defence customers. Furthermore, it has this week been reported that the company is also developing a network of hundreds of spy satellites under a classified contract for the US National Reconnaissance Office, signed in 2021.

Not only does this show the increasingly important role that space is now playing in military and defence, but also demonstrates how the government and military is becoming more reliant on private space entities, especially SpaceX.

While services provided by SpaceX give the US an advantage against its rivals in the space domain, it also once again raises the question about the power and influence over political and geopolitical matters commanded by commercial entities and individuals such as Elon Musk.

Writing this week for the Washington Post, Max Boot gave a very critical opinion of the SpaceX CEO, saying that Musk “pursues his own foreign policy”, referring to when he stepped-in to prevent Starlink being used by Ukrainian forces to attack the Russian naval fleet, and also referred to recent news that members of Congress have accused SpaceX of turning-off Starshield in and around Taiwan.

Boot also correctly states that there isn’t really any alternative to SpaceX at the moment, and so agencies and governments are relying on them for launches and connectivity. For example, the EU has this week, out of necessity, signed a deal with SpaceX for satellite launches, as they currently lack their own independant access to orbit.

However, this is set to change, with a number of companies looking to carry out maiden launches and expand their services this year. In-light of Musk’s tendency to weigh-in on geopolitics and foreign policy, will agencies and other customers soon choose to either move away or diversify from SpaceX services?

It will though take time, innovation and effective strategies to compete with SpaceX. We are also yet to see the impact of a truly usable and servicing Starship, which could again drastically reduce launch costs and force competitors out of the market.

UN buildings in Vienna (Adobe)

Critical year for space policy amid rising tensions

Legislative and geopolitical challenges are on the rise in the space sector, with recent threats of space militarisation, and the void of international laws that sufficiently govern the age of New Space and the prospect of extracting and utilising space resources. In his recent book “Who Owns The Moon”, AC Grayling discusses the effectiveness of UN law, namely the Outer Space Treaty (OST) 1967, which binds nations to peaceful and globally beneficial aspirations for space, including preventing nuclear weapons and forbidding territorial acquisition.

However, he also makes the point that throughout the treaty it makes reference to these “aspirations”, and that they are so just that. He writes “US statements of aspirations are made in the full knowledge that the attempt to give them effect in the form of international treaties and binding international law carries no guarantee that they will be realised,” (Grayling, 2024).

He goes on to make reference to instances where UN and international law has in the past been simply resisted or reshaped, such as when the US renegotiated the UN Law of the Seas to allow for seabed mining, or when the Trump administration simply abandoned the 2012 Paris Climate Accords.

The necessity to address these issues perhaps comes at the most pressing time. The US has made recent allegations that Russia intends to launch nuclear powered weapon in space, while Russia has this week warned the US against using SpaceX for spying capabilities, saying that in such a scenario, commercial entities would “become a legitimate target for retaliatory measures, including military ones”.

Meanwhile, this week Ukraine has indicated its desire to join the EU Space Programme and build closer ties to ESA, a move which could spark reaction from the Putin regime and have wider impact on the Ukraine war, which is sometimes dubbed the “first commercial space war”.

Opinion: Space is hard, and so is peaceful space

National and commercial activities in space are sharply on the rise, with a growing lunar launch cadence, international plans to build lunar bases and projects directed at developing a new commercial lunar economy. This goes without mentioning the exponential growth of satellite numbers in orbit and the birth of a new, sophisticated orbital infrastructure.

With this growth will always come the need to develop new frameworks, in order to guarantee the mutual benefits of space, based on peaceful uses. AC Grayling does make a valid point regarding UN law and its aspirations, and that they can simply be abandoned at any time. We are also stepping into new territory, with only comparative history able to inform us about what future scenarios in space may look like.

However, efforts are at least currently being made from most sides at UN level. The US and Japan have this week have supported a UN Security Council resolution calling on all nations not to deploy or develop nuclear weapons in space. This month China submitted a paper to the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) outlining a proposal to work with the UN in regards to managing resource extraction in outer space, keeping in-line with the OST. Furthermore, in January, Russia also submitted a proposal to COPUOS, proposing that “space science and technology should be used for the peaceful exploration and use of outer space in the interest of maintaining international peace”.

Amongst the flurry of accusations and growth of new space actors, there may at least still be some efforts being made to build a lasting peace in outer space.

Share this article

22 March 2024

iSpace and Astrobotic prep second lunar missions, SpaceX deepens influence in a pivotal year for space policy - Space News Roundup

Illustration of Astrobotic Griffin lander (Astrobotic)

Determination appears to be growing in the space sector, to build on recent successes and demonstrate technologies which will support and build a new lunar infrastructure and economy. Only in recent weeks we have reported news regarding companies such as Interlune, who plan to extract and retrieve Helium-3, as well as Russian and Chinese plans to build a nuclear reactor on the Moon by the 2030s.

This week Japanese startup iSpace announced plans to produce the first hydrogen on the Moon, as part of their Hakuto-R second lunar landing attempt later this year. Japanese company Takasago Thermal Engineering handed over their water electrolyser and storage tank system to iSpace on Monday. Once on the Moon the electrolyser will use surface-water to generate hydrogen and oxygen, which in future has the potential to produce rocket fuel and sustain life on the Moon.

Furthermore, not to be deterred from their failed first lunar mission, US startup Astrobotic are preparing for their second landing attempt, possibly at the end of this year. The company recently described how they’ve gathered much useful data from their first mission in January, using their Peregrine lander. Although the mission ultimately did not reach the Moon, it did manage to power-up most of its payloads, with NASA saying that one of their payloads, the Linear Energy Transfer Spectrometer (LETS), worked perfectly the whole time.

NASA drill among Astrobotic payloads

Astrobotic is now working towards the launch of their larger lander, the Griffin Mission One. Among the payloads, NASA will send their Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER), which is seen as a significant opportunity to learn about the presence and distribution of water at the lunar south pole. VIPER will carry a number of tools and spectrometers, including the Regolith and Ice Drill for Exploring New Terrains (TRIDENT), tasked with digging-up soil from the beneath the surface, which will then be analysed regarding the presence of hydrogen.

Such missions will provide significant insights, which in-turn help to inform agencies and companies better about the next steps towards to construction of a lunar infrastructure and habitats. Locating and refining water is one of the most pressing challenges to overcome, and is also being explored by private companies, such as Starpath Robotics.

SpaceX Starlink launch (SpaceX)

SpaceX to build US defence satellites, Musk influence again questioned

There’s no doubt that SpaceX are the leading force in the space sector right now, ever-increasing their launch-rate, expanding their Starlink mega-constellation and building landing systems for crewed lunar landings.

They are now also developing Starshield, derived from the Starlink constellation, but provided to military and defence customers. Furthermore, it has this week been reported that the company is also developing a network of hundreds of spy satellites under a classified contract for the US National Reconnaissance Office, signed in 2021.

Not only does this show the increasingly important role that space is now playing in military and defence, but also demonstrates how the government and military is becoming more reliant on private space entities, especially SpaceX.

While services provided by SpaceX give the US an advantage against its rivals in the space domain, it also once again raises the question about the power and influence over political and geopolitical matters commanded by commercial entities and individuals such as Elon Musk.

Writing this week for the Washington Post, Max Boot gave a very critical opinion of the SpaceX CEO, saying that Musk “pursues his own foreign policy”, referring to when he stepped-in to prevent Starlink being used by Ukrainian forces to attack the Russian naval fleet, and also referred to recent news that members of Congress have accused SpaceX of turning-off Starshield in and around Taiwan.

Boot also correctly states that there isn’t really any alternative to SpaceX at the moment, and so agencies and governments are relying on them for launches and connectivity. For example, the EU has this week, out of necessity, signed a deal with SpaceX for satellite launches, as they currently lack their own independant access to orbit.

However, this is set to change, with a number of companies looking to carry out maiden launches and expand their services this year. In-light of Musk’s tendency to weigh-in on geopolitics and foreign policy, will agencies and other customers soon choose to either move away or diversify from SpaceX services?

It will though take time, innovation and effective strategies to compete with SpaceX. We are also yet to see the impact of a truly usable and servicing Starship, which could again drastically reduce launch costs and force competitors out of the market.

UN buildings in Vienna (Adobe)

Critical year for space policy amid rising tensions

Legislative and geopolitical challenges are on the rise in the space sector, with recent threats of space militarisation, and the void of international laws that sufficiently govern the age of New Space and the prospect of extracting and utilising space resources. In his recent book “Who Owns The Moon”, AC Grayling discusses the effectiveness of UN law, namely the Outer Space Treaty (OST) 1967, which binds nations to peaceful and globally beneficial aspirations for space, including preventing nuclear weapons and forbidding territorial acquisition.

However, he also makes the point that throughout the treaty it makes reference to these “aspirations”, and that they are so just that. He writes “US statements of aspirations are made in the full knowledge that the attempt to give them effect in the form of international treaties and binding international law carries no guarantee that they will be realised,” (Grayling, 2024).

He goes on to make reference to instances where UN and international law has in the past been simply resisted or reshaped, such as when the US renegotiated the UN Law of the Seas to allow for seabed mining, or when the Trump administration simply abandoned the 2012 Paris Climate Accords.

The necessity to address these issues perhaps comes at the most pressing time. The US has made recent allegations that Russia intends to launch nuclear powered weapon in space, while Russia has this week warned the US against using SpaceX for spying capabilities, saying that in such a scenario, commercial entities would “become a legitimate target for retaliatory measures, including military ones”.

Meanwhile, this week Ukraine has indicated its desire to join the EU Space Programme and build closer ties to ESA, a move which could spark reaction from the Putin regime and have wider impact on the Ukraine war, which is sometimes dubbed the “first commercial space war”.

Opinion: Space is hard, and so is peaceful space

National and commercial activities in space are sharply on the rise, with a growing lunar launch cadence, international plans to build lunar bases and projects directed at developing a new commercial lunar economy. This goes without mentioning the exponential growth of satellite numbers in orbit and the birth of a new, sophisticated orbital infrastructure.

With this growth will always come the need to develop new frameworks, in order to guarantee the mutual benefits of space, based on peaceful uses. AC Grayling does make a valid point regarding UN law and its aspirations, and that they can simply be abandoned at any time. We are also stepping into new territory, with only comparative history able to inform us about what future scenarios in space may look like.

However, efforts are at least currently being made from most sides at UN level. The US and Japan have this week have supported a UN Security Council resolution calling on all nations not to deploy or develop nuclear weapons in space. This month China submitted a paper to the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) outlining a proposal to work with the UN in regards to managing resource extraction in outer space, keeping in-line with the OST. Furthermore, in January, Russia also submitted a proposal to COPUOS, proposing that “space science and technology should be used for the peaceful exploration and use of outer space in the interest of maintaining international peace”.

Amongst the flurry of accusations and growth of new space actors, there may at least still be some efforts being made to build a lasting peace in outer space.

Share this article

External Links

This Week

News articles posted here are not property of ANASDA GmbH and belong to their respected owners. Postings here are external links only.