21 December 2024

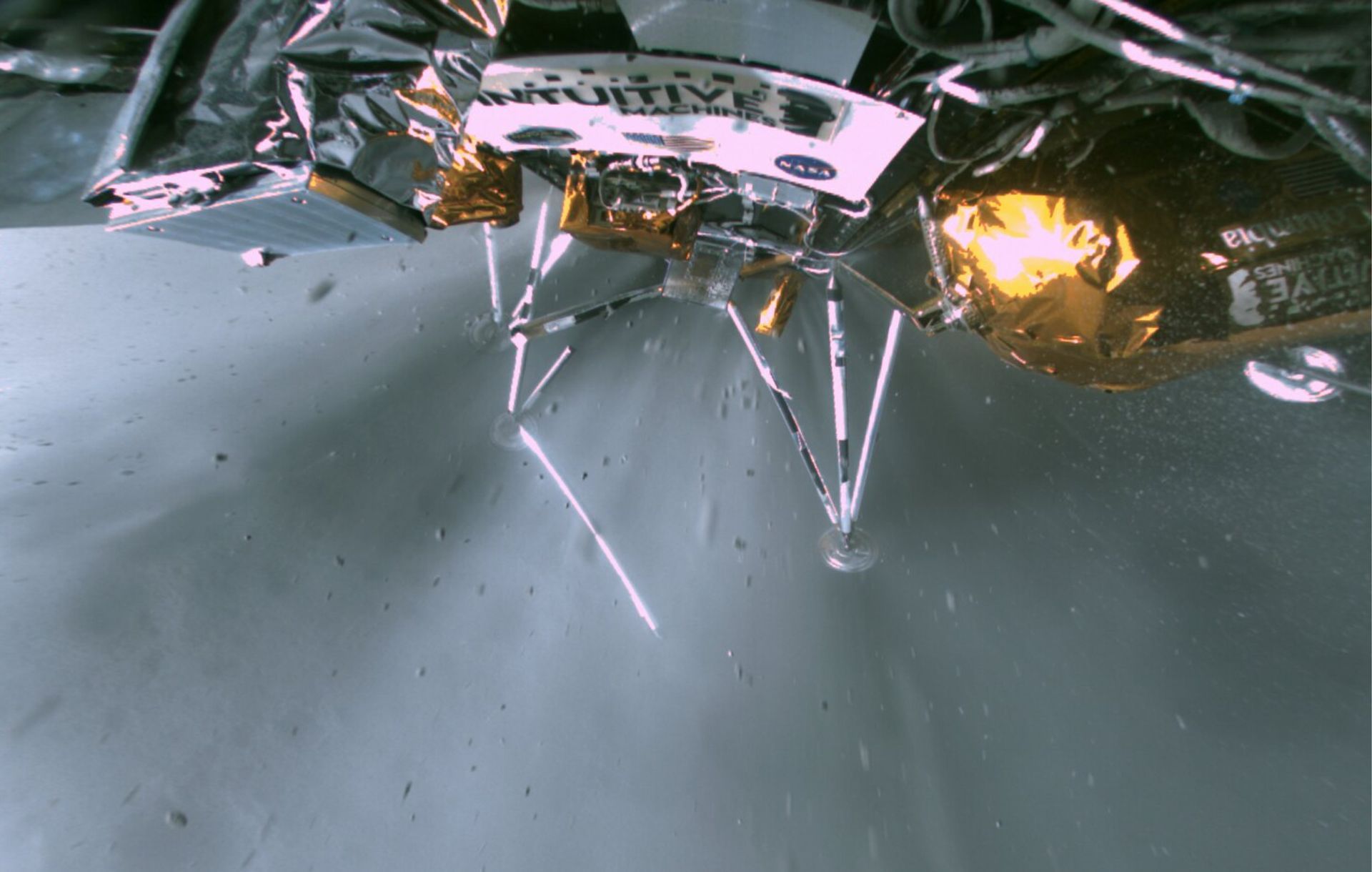

(Image: Intuitive Machines)

2024 marked another year of significant milestones for the expanding space sector, and we’ve been reporting throughout. From a renewed lunar race—the fifth nation to land on the Moon and the first-ever successful commercial lunar landing—to new efforts aimed at defining the future of global space governance, it would be a difficult task to outline all the developments within this article. However, we want to share what we believe to be some of the key highlights from this year (so far).

The development of new and existing space governance frameworks has been a prominent topic, particularly in relation to the adoption of the United Nations Pact for the Future. Action 56 of the pact directly addressed space governance, reaffirming commitment to the Outer Space Treaty—the cornerstone of international space law—ratified by all leading space nations. It also called for multi-stakeholder approaches and sought the participation of private sector and civil society entities in the intergovernmental process.

Importantly, the pact also called for the development of frameworks for space traffic management, space debris, and space resources, highlighting these areas as the “three pillars” of governance development. This, of course, gives good reason to be optimistic about the future of peaceful and sustainable space activities. A key theme at the UN World Space Forum this month was the importance of implementing the pact.

However, implementation may prove easier said than done, particularly as competition within the industry continues to grow.

Growth of Artemis Accords and China’s ILRS project

The growing divide between rival blocs—the Artemis Accords (AA) and the International Lunar Research Station project (ILRS)—has been a notable trend in 2024. What does this mean for the future of space governance?

One issue that could obstruct the implementation of the key themes outlined in the Pact for the Future is the increasing divergence and fragmentation among states and commercial actors. While many nations are signatories to the Outer Space Treaty, rival blocs led by the U.S. (Artemis Accords) and China (ILRS) have continued to expand their influence.

The Artemis Accords recently surpassed 50 member states, with Thailand becoming the 51st member just last week. This U.S.-led framework promotes a set of non-binding norms and principles for the peaceful use of outer space. It encourages partnerships with commercial actors and asserts that resource extraction in space is permissible under the guidance of the Outer Space Treaty. Additionally, U.S. national law explicitly legislates the extraction and utilization of space resources.

Meanwhile, China’s International Lunar Research Station project (ILRS), which aims to establish a lunar base by the 2030s, has attracted significant support. According to China’s Deep Space Exploration Lab, the ILRS has secured commitments from over 10 companies and more than 40 international institutions.

(Image: Firefly Aerospace)

Lunar governance and a commercial lunar race (again) and ATLAC

In June, we were fortunate to attend the first UN Conference on Sustainable Lunar Activities, where delegates, commercial companies, academics, and other experts discussed pressing challenges related to the safe, peaceful, and sustainable exploration and use of the Moon.

A key positive outcome was the recognition that stakeholders share more common ground than differences, with a collective urgency for transparency, interoperability, and exploring the benefits the Moon can provide to all humanity. Furthermore, following the conference, the annual meeting of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) took place, where delegates adopted Romania’s proposal for the Action Team on Lunar Activities Consultation (ATLAC).

This mechanism aims to provide a platform for managing lunar governance issues, although its exact functionality remains to be seen. An action plan is expected to be delivered in 2025.

Another lunar “race”, a flurry of partnership deals before year-end

The development of new frameworks comes at a critical time, as we witness a growing lunar mission cadence, with ESA estimating there could be around 100 missions to the Moon by the end of the decade.

At the beginning of the year, we saw a trio of missions attempt to land on the Moon. Japan became the fifth nation to safely land on the Moon, while Intuitive Machines (US) made history as the first commercial company to achieve a soft landing. Unfortunately, Astrobotic (US) experienced a mission failure due to a fuel leak on the lander.

Fast forward to January 2025, and we find ourselves in a similar situation, this time with another trio of commercial landers preparing for launch. In mid-January, both iSpace and Firefly are set to launch aboard the same SpaceX Falcon-9 on their journeys to the Moon. iSpace is making its second attempt following a crash landing in April 2023. This mission aims to deliver its RESILIENCE lunar rover, which will excavate lunar soil and transfer it to NASA, potentially marking the first commercial lunar transaction.

Firefly, meanwhile, is contracted under NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program and aims to land in a northern hemisphere region of the Moon. Launching no sooner than February, Intuitive Machines will attempt its IM-2 mission to the Moon, also contracted under NASA CLPS. Among the payloads, the company will deliver NASA’s PRIME-1, which will drill into the lunar surface to search for water ice.

Looking ahead, Intuitive Machines also plans to launch its IM-3 mission in 2025, while Astrobotic aims to launch its Griffin lander in autumn of the same year. Additionally, Firefly has a second mission planned for 2026 and recently secured another NASA contract to send its Blue Ghost lander to the Moon in 2028.

——————————————————————

It will be crucial to sustain efforts in building and refining frameworks for space and lunar governance as we see more agencies and commercial entities contributing to the lunar economy. The Pact for the Future is a positive step, but implementation remains key. While space holds the potential to foster international cooperation, we are also entering an era where space services are rapidly increasing in value, connecting the planet, addressing sustainability goals (SDGs), and offering opportunities for mineral wealth.

With growing value comes heightened competition—a scenario that becomes especially precarious when technological advancements outpace law-making. In 2025, it will be essential for all stakeholders to raise awareness, build capacity, and amplify efforts to reach a consensus on how to develop the future of space for peaceful and sustainable use.

For a comprehensive look at the developments in the space industry in 2024, covering technology and business development, innovation, the lunar economy, law, policy and international relations, look out for the publication of our full Annual Report.

(Image: Intuitive Machines)

21 December 2024

Reflecting on 2024: Space Governance, Space Blocs and a Commercial Lunar Race (again) - Space News Roundup

2024 marked another year of significant milestones for the expanding space sector, and we’ve been reporting throughout. From a renewed lunar race—the fifth nation to land on the Moon and the first-ever successful commercial lunar landing—to new efforts aimed at defining the future of global space governance, it would be a difficult task to outline all the developments within this article. However, we want to share what we believe to be some of the key highlights from this year (so far).

The development of new and existing space governance frameworks has been a prominent topic, particularly in relation to the adoption of the United Nations Pact for the Future. Action 56 of the pact directly addressed space governance, reaffirming commitment to the Outer Space Treaty—the cornerstone of international space law—ratified by all leading space nations. It also called for multi-stakeholder approaches and sought the participation of private sector and civil society entities in the intergovernmental process.

Importantly, the pact also called for the development of frameworks for space traffic management, space debris, and space resources, highlighting these areas as the “three pillars” of governance development. This, of course, gives good reason to be optimistic about the future of peaceful and sustainable space activities. A key theme at the UN World Space Forum this month was the importance of implementing the pact.

However, implementation may prove easier said than done, particularly as competition within the industry continues to grow.

Growth of Artemis Accords and China’s ILRS project

The growing divide between rival blocs—the Artemis Accords (AA) and the International Lunar Research Station project (ILRS)—has been a notable trend in 2024. What does this mean for the future of space governance?

One issue that could obstruct the implementation of the key themes outlined in the Pact for the Future is the increasing divergence and fragmentation among states and commercial actors. While many nations are signatories to the Outer Space Treaty, rival blocs led by the U.S. (Artemis Accords) and China (ILRS) have continued to expand their influence.

The Artemis Accords recently surpassed 50 member states, with Thailand becoming the 51st member just last week. This U.S.-led framework promotes a set of non-binding norms and principles for the peaceful use of outer space. It encourages partnerships with commercial actors and asserts that resource extraction in space is permissible under the guidance of the Outer Space Treaty. Additionally, U.S. national law explicitly legislates the extraction and utilization of space resources.

Meanwhile, China’s International Lunar Research Station project (ILRS), which aims to establish a lunar base by the 2030s, has attracted significant support. According to China’s Deep Space Exploration Lab, the ILRS has secured commitments from over 10 companies and more than 40 international institutions.

Lunar governance and a commercial lunar race (again) and ATLAC

In June, we were fortunate to attend the first UN Conference on Sustainable Lunar Activities, where delegates, commercial companies, academics, and other experts discussed pressing challenges related to the safe, peaceful, and sustainable exploration and use of the Moon.

A key positive outcome was the recognition that stakeholders share more common ground than differences, with a collective urgency for transparency, interoperability, and exploring the benefits the Moon can provide to all humanity. Furthermore, following the conference, the annual meeting of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) took place, where delegates adopted Romania’s proposal for the Action Team on Lunar Activities Consultation (ATLAC).

This mechanism aims to provide a platform for managing lunar governance issues, although its exact functionality remains to be seen. An action plan is expected to be delivered in 2025.

Another lunar “race”, a flurry of partnership deals before year-end

The development of new frameworks comes at a critical time, as we witness a growing lunar mission cadence, with ESA estimating there could be around 100 missions to the Moon by the end of the decade.

At the beginning of the year, we saw a trio of missions attempt to land on the Moon. Japan became the fifth nation to safely land on the Moon, while Intuitive Machines (US) made history as the first commercial company to achieve a soft landing. Unfortunately, Astrobotic (US) experienced a mission failure due to a fuel leak on the lander.

Fast forward to January 2025, and we find ourselves in a similar situation, this time with another trio of commercial landers preparing for launch. In mid-January, both iSpace and Firefly are set to launch aboard the same SpaceX Falcon-9 on their journeys to the Moon. iSpace is making its second attempt following a crash landing in April 2023. This mission aims to deliver its RESILIENCE lunar rover, which will excavate lunar soil and transfer it to NASA, potentially marking the first commercial lunar transaction.

Firefly, meanwhile, is contracted under NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program and aims to land in a northern hemisphere region of the Moon. Launching no sooner than February, Intuitive Machines will attempt its IM-2 mission to the Moon, also contracted under NASA CLPS. Among the payloads, the company will deliver NASA’s PRIME-1, which will drill into the lunar surface to search for water ice.

Looking ahead, Intuitive Machines also plans to launch its IM-3 mission in 2025, while Astrobotic aims to launch its Griffin lander in autumn of the same year. Additionally, Firefly has a second mission planned for 2026 and recently secured another NASA contract to send its Blue Ghost lander to the Moon in 2028.

——————————————————————

It will be crucial to sustain efforts in building and refining frameworks for space and lunar governance as we see more agencies and commercial entities contributing to the lunar economy. The Pact for the Future is a positive step, but implementation remains key. While space holds the potential to foster international cooperation, we are also entering an era where space services are rapidly increasing in value, connecting the planet, addressing sustainability goals (SDGs), and offering opportunities for mineral wealth.

With growing value comes heightened competition—a scenario that becomes especially precarious when technological advancements outpace law-making. In 2025, it will be essential for all stakeholders to raise awareness, build capacity, and amplify efforts to reach a consensus on how to develop the future of space for peaceful and sustainable use.

For a comprehensive look at the developments in the space industry in 2024, covering technology and business development, innovation, the lunar economy, law, policy and international relations, look out for the publication of our full Annual Report.

Share this article

21 December 2024

Reflecting on 2024: Space Governance, Space Blocs and a Commercial Lunar Race (again) - Space News Roundup

(Image: Intuitive Machines)

2024 marked another year of significant milestones for the expanding space sector, and we’ve been reporting throughout. From a renewed lunar race—the fifth nation to land on the Moon and the first-ever successful commercial lunar landing—to new efforts aimed at defining the future of global space governance, it would be a difficult task to outline all the developments within this article. However, we want to share what we believe to be some of the key highlights from this year (so far).

The development of new and existing space governance frameworks has been a prominent topic, particularly in relation to the adoption of the United Nations Pact for the Future. Action 56 of the pact directly addressed space governance, reaffirming commitment to the Outer Space Treaty—the cornerstone of international space law—ratified by all leading space nations. It also called for multi-stakeholder approaches and sought the participation of private sector and civil society entities in the intergovernmental process.

Importantly, the pact also called for the development of frameworks for space traffic management, space debris, and space resources, highlighting these areas as the “three pillars” of governance development. This, of course, gives good reason to be optimistic about the future of peaceful and sustainable space activities. A key theme at the UN World Space Forum this month was the importance of implementing the pact.

However, implementation may prove easier said than done, particularly as competition within the industry continues to grow.

Growth of Artemis Accords and China’s ILRS project

The growing divide between rival blocs—the Artemis Accords (AA) and the International Lunar Research Station project (ILRS)—has been a notable trend in 2024. What does this mean for the future of space governance?

One issue that could obstruct the implementation of the key themes outlined in the Pact for the Future is the increasing divergence and fragmentation among states and commercial actors. While many nations are signatories to the Outer Space Treaty, rival blocs led by the U.S. (Artemis Accords) and China (ILRS) have continued to expand their influence.

The Artemis Accords recently surpassed 50 member states, with Thailand becoming the 51st member just last week. This U.S.-led framework promotes a set of non-binding norms and principles for the peaceful use of outer space. It encourages partnerships with commercial actors and asserts that resource extraction in space is permissible under the guidance of the Outer Space Treaty. Additionally, U.S. national law explicitly legislates the extraction and utilization of space resources.

Meanwhile, China’s International Lunar Research Station project (ILRS), which aims to establish a lunar base by the 2030s, has attracted significant support. According to China’s Deep Space Exploration Lab, the ILRS has secured commitments from over 10 companies and more than 40 international institutions.

(Image: Firefly Aerospace)

Lunar governance and a commercial lunar race (again) and ATLAC

In June, we were fortunate to attend the first UN Conference on Sustainable Lunar Activities, where delegates, commercial companies, academics, and other experts discussed pressing challenges related to the safe, peaceful, and sustainable exploration and use of the Moon.

A key positive outcome was the recognition that stakeholders share more common ground than differences, with a collective urgency for transparency, interoperability, and exploring the benefits the Moon can provide to all humanity. Furthermore, following the conference, the annual meeting of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) took place, where delegates adopted Romania’s proposal for the Action Team on Lunar Activities Consultation (ATLAC).

This mechanism aims to provide a platform for managing lunar governance issues, although its exact functionality remains to be seen. An action plan is expected to be delivered in 2025.

Another lunar “race”, a flurry of partnership deals before year-end

The development of new frameworks comes at a critical time, as we witness a growing lunar mission cadence, with ESA estimating there could be around 100 missions to the Moon by the end of the decade.

At the beginning of the year, we saw a trio of missions attempt to land on the Moon. Japan became the fifth nation to safely land on the Moon, while Intuitive Machines (US) made history as the first commercial company to achieve a soft landing. Unfortunately, Astrobotic (US) experienced a mission failure due to a fuel leak on the lander.

Fast forward to January 2025, and we find ourselves in a similar situation, this time with another trio of commercial landers preparing for launch. In mid-January, both iSpace and Firefly are set to launch aboard the same SpaceX Falcon-9 on their journeys to the Moon. iSpace is making its second attempt following a crash landing in April 2023. This mission aims to deliver its RESILIENCE lunar rover, which will excavate lunar soil and transfer it to NASA, potentially marking the first commercial lunar transaction.

Firefly, meanwhile, is contracted under NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program and aims to land in a northern hemisphere region of the Moon. Launching no sooner than February, Intuitive Machines will attempt its IM-2 mission to the Moon, also contracted under NASA CLPS. Among the payloads, the company will deliver NASA’s PRIME-1, which will drill into the lunar surface to search for water ice.

Looking ahead, Intuitive Machines also plans to launch its IM-3 mission in 2025, while Astrobotic aims to launch its Griffin lander in autumn of the same year. Additionally, Firefly has a second mission planned for 2026 and recently secured another NASA contract to send its Blue Ghost lander to the Moon in 2028.

——————————————————————

It will be crucial to sustain efforts in building and refining frameworks for space and lunar governance as we see more agencies and commercial entities contributing to the lunar economy. The Pact for the Future is a positive step, but implementation remains key. While space holds the potential to foster international cooperation, we are also entering an era where space services are rapidly increasing in value, connecting the planet, addressing sustainability goals (SDGs), and offering opportunities for mineral wealth.

With growing value comes heightened competition—a scenario that becomes especially precarious when technological advancements outpace law-making. In 2025, it will be essential for all stakeholders to raise awareness, build capacity, and amplify efforts to reach a consensus on how to develop the future of space for peaceful and sustainable use.

For a comprehensive look at the developments in the space industry in 2024, covering technology and business development, innovation, the lunar economy, law, policy and international relations, look out for the publication of our full Annual Report.

Share this article