20 September 2024

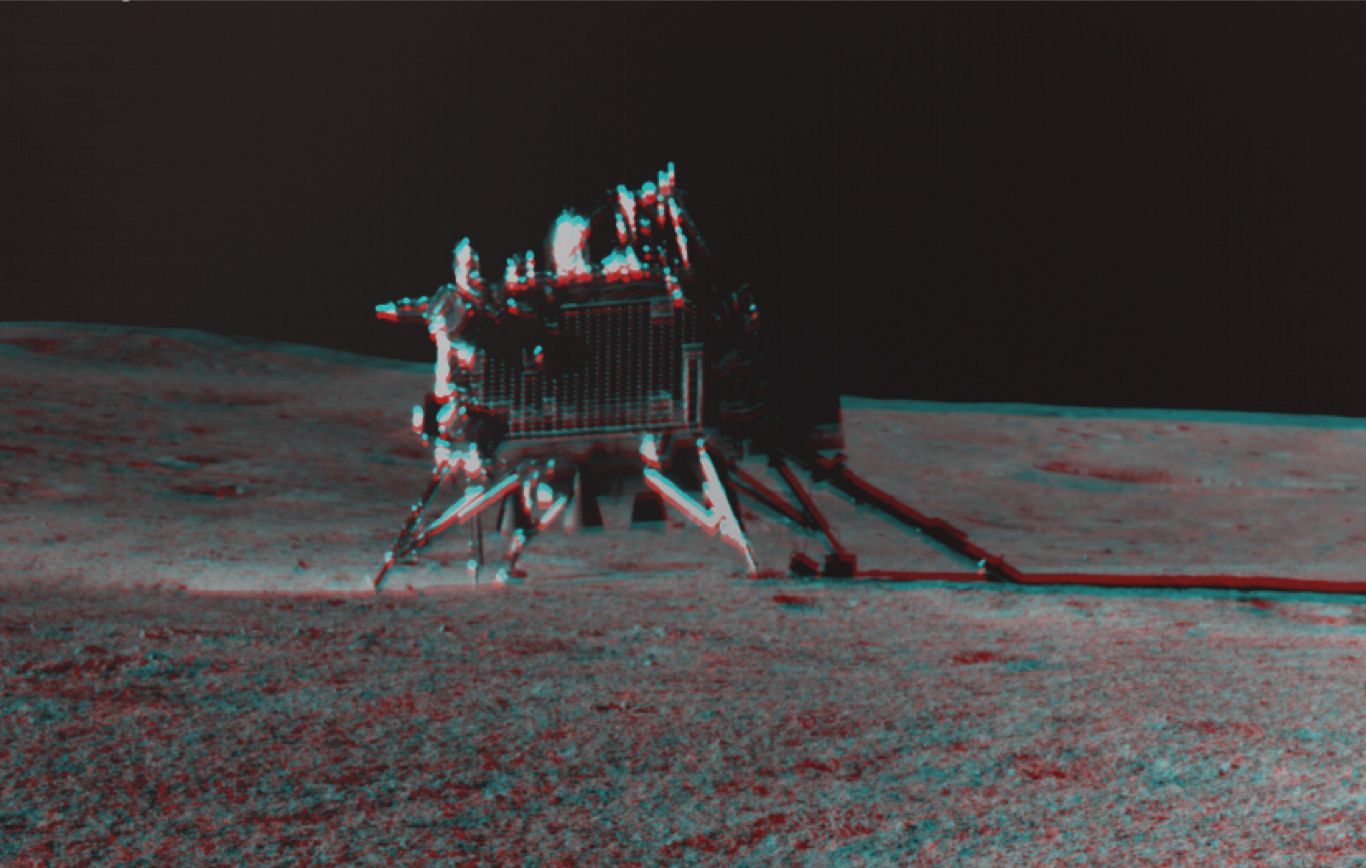

Chandrayaan-3 on the Moon (Image: ISRO)

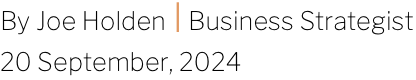

India is rapidly emerging as a significant player in the space sector, aiming to capture around 8% of the global space economy, projected to be worth $1.8 trillion by 2033. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) made headlines in August last year by becoming only the fourth nation to land on the Moon, achieving this milestone at a fraction of the typical cost—spending just $75 million. ISRO kept costs low through innovative strategies like taking a longer route to the Moon, which allowed for the use of cheaper, less powerful thrusters.

In recent developments, the Indian government has greenlit Chandrayaan-4, a lunar sample return mission scheduled for launch in 2028. This complex mission, which will involve two separate launches, is expected to lay the groundwork for India’s first crewed lunar landing by 2040. Additionally, India’s ambitious Venus Orbiter Mission (VOM), targeting a March 2028 launch, has been approved, along with plans for Bharatiya Antariksh Station (BAS-1), India’s first space station module, also slated for a 2028 launch.

Furthermore, India is advancing its Next Generation Launch Vehicle (NGLV), designed for higher payload capacity and reusability, which will provide the country with more sustainable and cost-effective access to space.

According to an article from The Print, India has signed cooperative agreements with 61 countries over the past five years, positioning itself as a "reliable market" for space manufacturing and launch services and as a trusted partner for countries with developing space programs. India’s growing stature as a space leader has also caught the attention of the US. In 2023, India signed the US-led Artemis Accords, a non-binding regulatory framework governing the peaceful exploration of outer space. Yet, India remains open to partnerships with both Russia and China, and has expressed interest in collaborative efforts, including developing a nuclear power plant on the Moon.

Anil Prakash, Director General of the SatCom Industry Association of India (SIA-India), highlighted in a recent Space News article that the relationship between India and the US "has come into stronger focus" in recent years. He pointed to opportunities for India to cooperate on NASA’s Lunar Gateway Program, a collaborative effort vital for the overall success of the space sector.

India's expanding influence underscores how new leadership can open fresh avenues for diplomacy and dialogue—an increasingly critical factor in maintaining peaceful and sustainable development in space, especially as trust and international relations on Earth face ongoing challenges.

(Image: Pexels)

Space Forge expand to US, UK emerging as hub of global cooperation

India is not alone in its pursuit of developing sovereign space capacity and a robust space economy. The United Kingdom has similarly set ambitious goals, aiming to capture a significant share of the global space market. The UK is on the verge of becoming a key hub for European launch activities, with spaceports in Scotland expected to host their first launches by 2025. In total, the UK is currently developing seven spaceports, positioning itself as a launch leader in Europe.

The UK is also at the forefront of satellite development, ranking among the top five countries with the most registered operational satellites in orbit. Recent government investments have further strengthened the UK's space industry, with initiatives like the Space Clusters Infrastructure Fund aimed at boosting the economy, developing advanced skills, and creating jobs within the sector.

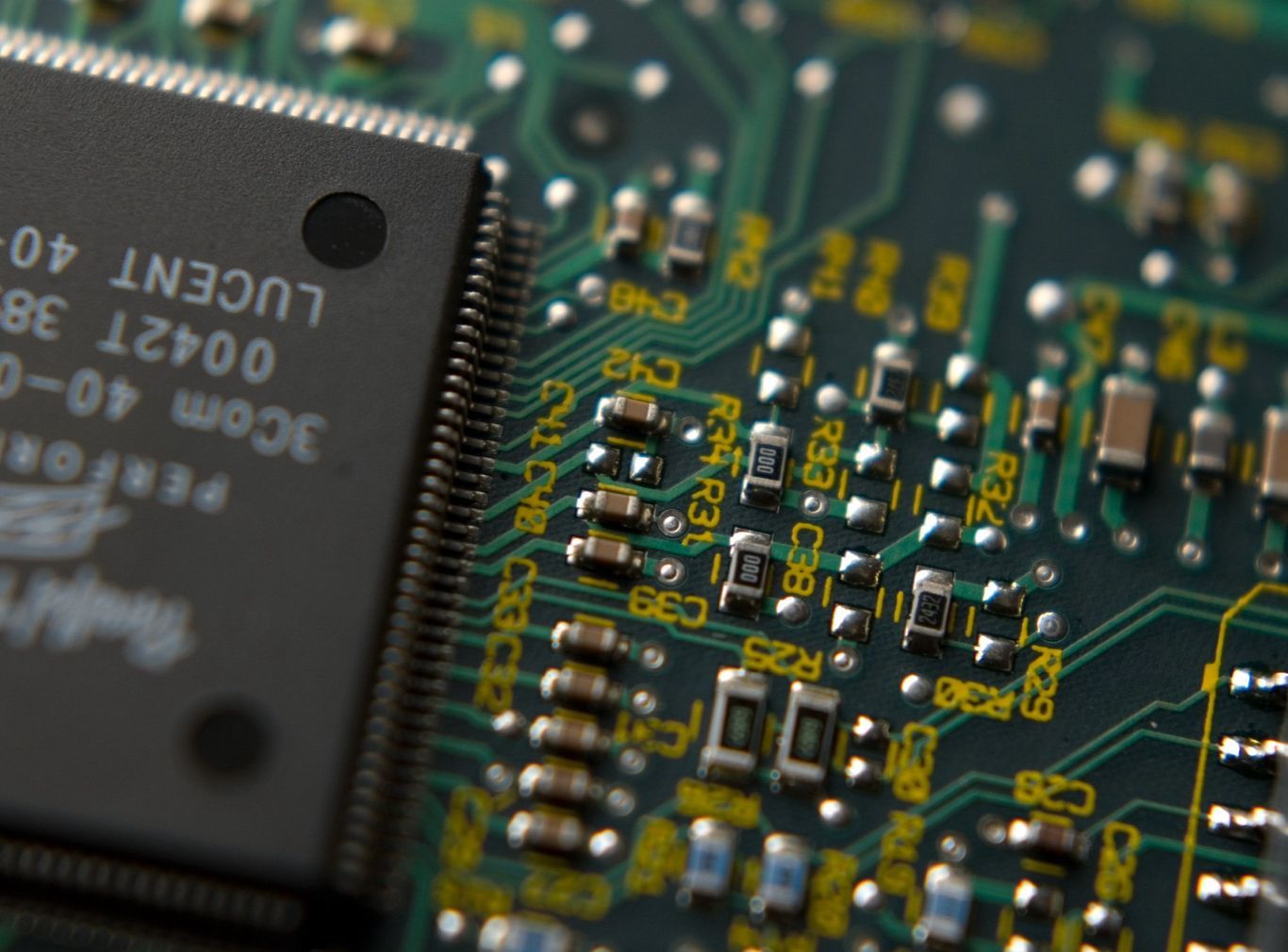

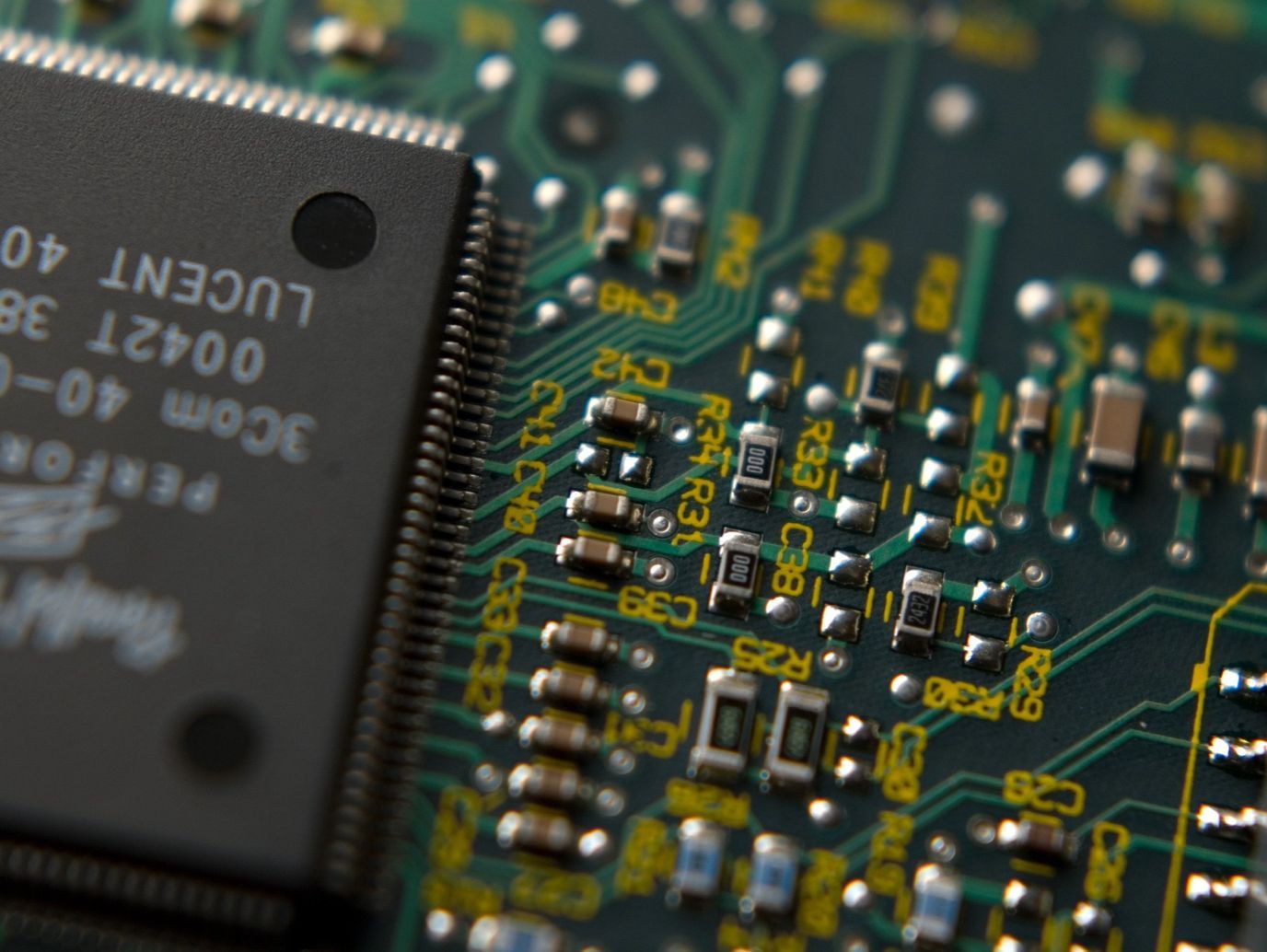

One notable beneficiary of this fund is Welsh company Space Forge, which secured £7.9 million at the end of last year to establish a National Microgravity Research Centre. Space Forge specialises in in-space manufacturing (ISM), utilising the unique conditions of Earth's orbit to produce advanced materials—such as those used in semiconductors—and then returning them to Earth. Just last week, Space Forge announced the opening of a new office in Florida, near the Kennedy Space Center, to help revolutionise the US semiconductor market.

This move comes in the wake of the Biden Administration’s 2022 US CHIPS Act, which aims to strengthen domestic semiconductor research and production. Space Forge is actively recruiting for a ‘Head of Semiconductors’ in the US to support this effort.

In addition to growing its space economy, the UK is fostering international collaboration. In August 2023, the UK Space Agency announced the first recipients of its International Bilateral Fund, a program designed to strengthen global partnerships. Since then, the fund has supported projects with the USA, Australia, Japan, Canada, Germany, Singapore, the UAE, Bahrain, and others. This year, the fund received an additional £13 million to continue expanding these partnerships.

Like India, the UK is emerging as a vital player in space activity and collaboration. Joint efforts between nations will be essential not only for driving innovation, technology transfer, and knowledge sharing but also for ensuring that cooperation remains the foundation of peaceful space development.

ESA's Ariane-6 (Image: ESA - S. Corvaja)

How can legacy agencies keep pace in an ever-competitive space economy?

While the UK aims to lead in building a new European space architecture, Sinead O’Sullivan, writing in a recent Financial Times op-ed, highlights challenges facing both NASA and ESA. Her analysis draws from two reports—one by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and another by former European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi on European competitiveness.

O’Sullivan argues that both NASA and ESA, as large, publicly funded institutions, struggle to adapt quickly to modern economic and political realities (FT, 2024). NASA has increasingly turned to private companies, as seen with the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, but in doing so, it has lost talented engineers and scientists to the private sector. ESA, by contrast, has failed to attract enough private sector support.

O’Sullivan points to the launch sector as an example, where ESA's long-awaited Ariane-6 rocket has been delivered at a high cost for a vehicle that lacks reusability—a key factor in modern spaceflight efficiency.

As a solution, O’Sullivan proposes that NASA focus on long-term projects that serve humanity, while ESA should further incentivise private-sector collaboration and provide stronger support to space startups.

These strategies could prove crucial for both NASA and ESA, as the space industry is evolving at a rapid pace. Recent developments from nations like India and the UK demonstrate the determination of growing space nations, driven by nationally-funded programs that stimulate private innovation and growth.

Both agencies do of course see the immense value in the private sector and spearheading national programmes in space exploration. The US leads the way in utilising commercial technology for national space endeavours, such as through their Artemis programme, taking humans back to the Moon and establishing a permanent lunar infrastructure. ESA has only last year indicated its desire to utilise commercial launch services, and draw the curtain on the era of publicly-funded Ariane rockets, and also indicated their goal to establish a presence on the Moon within the next decade.

However, it will also be necessary to respond more quickly to the economic, political and geopolitical challenges that they now face in an expanding space industry.

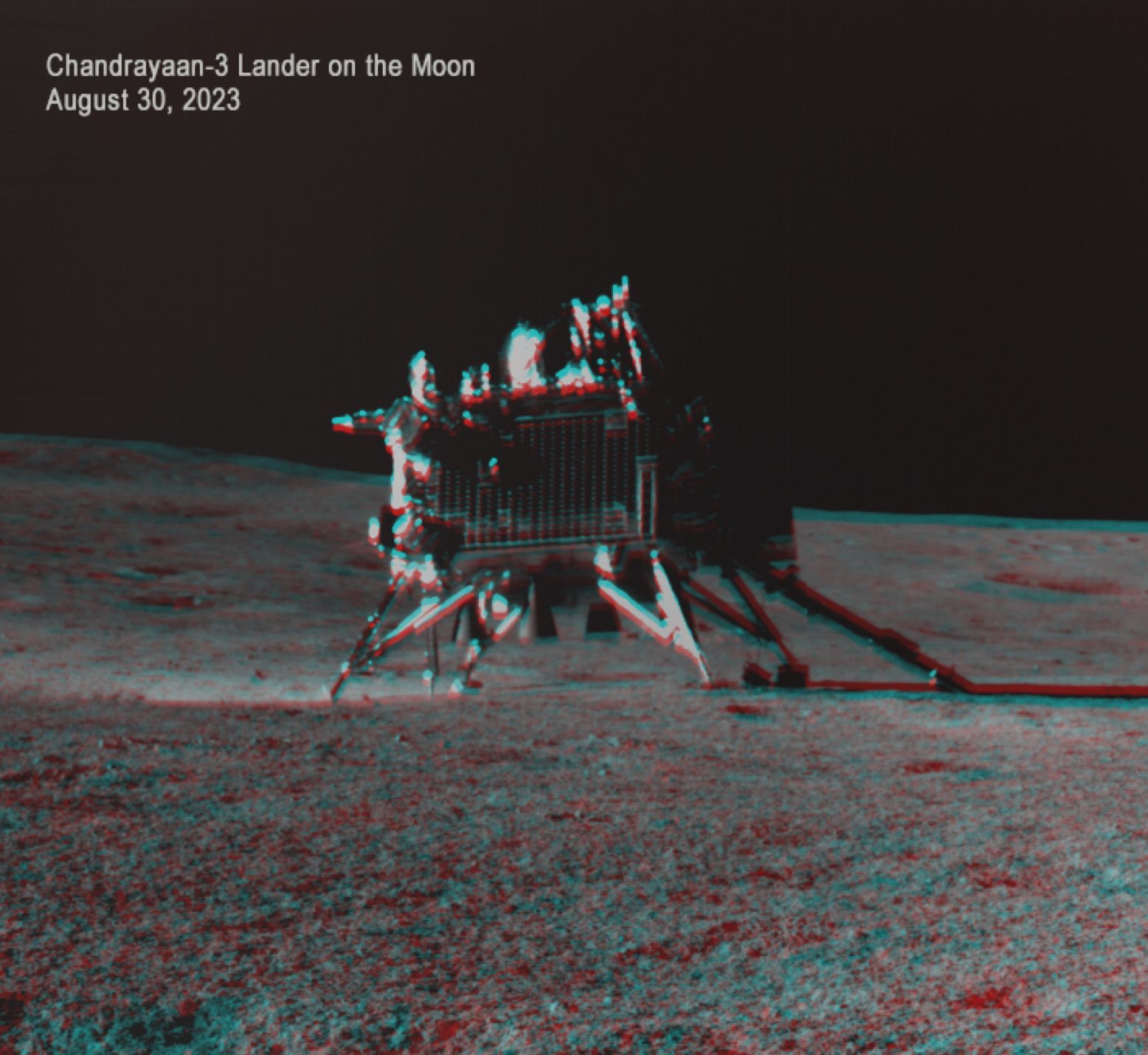

Chandrayaan-3 on the Moon (Image: ISRO)

20 September 2024

India Announce Outer Space Missions, UK’s Space Forge Expansion, and the Need for NASA and ESA to Adapt in a Rapidly Evolving Space Sector - Space News Roundup

India is rapidly emerging as a significant player in the space sector, aiming to capture around 8% of the global space economy, projected to be worth $1.8 trillion by 2033. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) made headlines in August last year by becoming only the fourth nation to land on the Moon, achieving this milestone at a fraction of the typical cost—spending just $75 million. ISRO kept costs low through innovative strategies like taking a longer route to the Moon, which allowed for the use of cheaper, less powerful thrusters.

In recent developments, the Indian government has greenlit Chandrayaan-4, a lunar sample return mission scheduled for launch in 2028. This complex mission, which will involve two separate launches, is expected to lay the groundwork for India’s first crewed lunar landing by 2040. Additionally, India’s ambitious Venus Orbiter Mission (VOM), targeting a March 2028 launch, has been approved, along with plans for Bharatiya Antariksh Station (BAS-1), India’s first space station module, also slated for a 2028 launch.

Furthermore, India is advancing its Next Generation Launch Vehicle (NGLV), designed for higher payload capacity and reusability, which will provide the country with more sustainable and cost-effective access to space.

According to an article from The Print, India has signed cooperative agreements with 61 countries over the past five years, positioning itself as a "reliable market" for space manufacturing and launch services and as a trusted partner for countries with developing space programs. India’s growing stature as a space leader has also caught the attention of the US. In 2023, India signed the US-led Artemis Accords, a non-binding regulatory framework governing the peaceful exploration of outer space. Yet, India remains open to partnerships with both Russia and China, and has expressed interest in collaborative efforts, including developing a nuclear power plant on the Moon.

Anil Prakash, Director General of the SatCom Industry Association of India (SIA-India), highlighted in a recent Space News article that the relationship between India and the US "has come into stronger focus" in recent years. He pointed to opportunities for India to cooperate on NASA’s Lunar Gateway Program, a collaborative effort vital for the overall success of the space sector.

India's expanding influence underscores how new leadership can open fresh avenues for diplomacy and dialogue—an increasingly critical factor in maintaining peaceful and sustainable development in space, especially as trust and international relations on Earth face ongoing challenges.

(Image: Pexels)

Space Forge expand to US, UK emerging as hub of global cooperation

India is not alone in its pursuit of developing sovereign space capacity and a robust space economy. The United Kingdom has similarly set ambitious goals, aiming to capture a significant share of the global space market. The UK is on the verge of becoming a key hub for European launch activities, with spaceports in Scotland expected to host their first launches by 2025. In total, the UK is currently developing seven spaceports, positioning itself as a launch leader in Europe.

The UK is also at the forefront of satellite development, ranking among the top five countries with the most registered operational satellites in orbit. Recent government investments have further strengthened the UK's space industry, with initiatives like the Space Clusters Infrastructure Fund aimed at boosting the economy, developing advanced skills, and creating jobs within the sector.

One notable beneficiary of this fund is Welsh company Space Forge, which secured £7.9 million at the end of last year to establish a National Microgravity Research Centre. Space Forge specialises in in-space manufacturing (ISM), utilising the unique conditions of Earth's orbit to produce advanced materials—such as those used in semiconductors—and then returning them to Earth. Just last week, Space Forge announced the opening of a new office in Florida, near the Kennedy Space Center, to help revolutionise the US semiconductor market.

This move comes in the wake of the Biden Administration’s 2022 US CHIPS Act, which aims to strengthen domestic semiconductor research and production. Space Forge is actively recruiting for a ‘Head of Semiconductors’ in the US to support this effort.

In addition to growing its space economy, the UK is fostering international collaboration. In August 2023, the UK Space Agency announced the first recipients of its International Bilateral Fund, a program designed to strengthen global partnerships. Since then, the fund has supported projects with the USA, Australia, Japan, Canada, Germany, Singapore, the UAE, Bahrain, and others. This year, the fund received an additional £13 million to continue expanding these partnerships.

Like India, the UK is emerging as a vital player in space activity and collaboration. Joint efforts between nations will be essential not only for driving innovation, technology transfer, and knowledge sharing but also for ensuring that cooperation remains the foundation of peaceful space development.

ESA's Ariane-6 (Image: ESA - S. Corvaja)

How can legacy agencies keep pace in an ever-competitive space economy?

While the UK aims to lead in building a new European space architecture, Sinead O’Sullivan, writing in a recent Financial Times op-ed, highlights challenges facing both NASA and ESA. Her analysis draws from two reports—one by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and another by former European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi on European competitiveness.

O’Sullivan argues that both NASA and ESA, as large, publicly funded institutions, struggle to adapt quickly to modern economic and political realities (FT, 2024). NASA has increasingly turned to private companies, as seen with the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, but in doing so, it has lost talented engineers and scientists to the private sector. ESA, by contrast, has failed to attract enough private sector support.

O’Sullivan points to the launch sector as an example, where ESA's long-awaited Ariane-6 rocket has been delivered at a high cost for a vehicle that lacks reusability—a key factor in modern spaceflight efficiency.

As a solution, O’Sullivan proposes that NASA focus on long-term projects that serve humanity, while ESA should further incentivise private-sector collaboration and provide stronger support to space startups.

These strategies could prove crucial for both NASA and ESA, as the space industry is evolving at a rapid pace. Recent developments from nations like India and the UK demonstrate the determination of growing space nations, driven by nationally-funded programs that stimulate private innovation and growth.

Both agencies do of course see the immense value in the private sector and spearheading national programmes in space exploration. The US leads the way in utilising commercial technology for national space endeavours, such as through their Artemis programme, taking humans back to the Moon and establishing a permanent lunar infrastructure. ESA has only last year indicated its desire to utilise commercial launch services, and draw the curtain on the era of publicly-funded Ariane rockets, and also indicated their goal to establish a presence on the Moon within the next decade.

However, it will also be necessary to respond more quickly to the economic, political and geopolitical challenges that they now face in an expanding space industry.

Share this article

20 September 2024

India Announce Outer Space Missions, UK’s Space Forge Expansion, and the Need for NASA and ESA to Adapt in a Rapidly Evolving Space Sector - Space News Roundup

Chandrayaan-3 on the Moon (Image: ISRO)

India is rapidly emerging as a significant player in the space sector, aiming to capture around 8% of the global space economy, projected to be worth $1.8 trillion by 2033. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) made headlines in August last year by becoming only the fourth nation to land on the Moon, achieving this milestone at a fraction of the typical cost—spending just $75 million. ISRO kept costs low through innovative strategies like taking a longer route to the Moon, which allowed for the use of cheaper, less powerful thrusters.

In recent developments, the Indian government has greenlit Chandrayaan-4, a lunar sample return mission scheduled for launch in 2028. This complex mission, which will involve two separate launches, is expected to lay the groundwork for India’s first crewed lunar landing by 2040. Additionally, India’s ambitious Venus Orbiter Mission (VOM), targeting a March 2028 launch, has been approved, along with plans for Bharatiya Antariksh Station (BAS-1), India’s first space station module, also slated for a 2028 launch.

Furthermore, India is advancing its Next Generation Launch Vehicle (NGLV), designed for higher payload capacity and reusability, which will provide the country with more sustainable and cost-effective access to space.

According to an article from The Print, India has signed cooperative agreements with 61 countries over the past five years, positioning itself as a "reliable market" for space manufacturing and launch services and as a trusted partner for countries with developing space programs. India’s growing stature as a space leader has also caught the attention of the US. In 2023, India signed the US-led Artemis Accords, a non-binding regulatory framework governing the peaceful exploration of outer space. Yet, India remains open to partnerships with both Russia and China, and has expressed interest in collaborative efforts, including developing a nuclear power plant on the Moon.

Anil Prakash, Director General of the SatCom Industry Association of India (SIA-India), highlighted in a recent Space News article that the relationship between India and the US "has come into stronger focus" in recent years. He pointed to opportunities for India to cooperate on NASA’s Lunar Gateway Program, a collaborative effort vital for the overall success of the space sector.

India's expanding influence underscores how new leadership can open fresh avenues for diplomacy and dialogue—an increasingly critical factor in maintaining peaceful and sustainable development in space, especially as trust and international relations on Earth face ongoing challenges.

(Image: Pexels)

Space Forge expand to US, UK emerging as hub of global cooperation

India is not alone in its pursuit of developing sovereign space capacity and a robust space economy. The United Kingdom has similarly set ambitious goals, aiming to capture a significant share of the global space market. The UK is on the verge of becoming a key hub for European launch activities, with spaceports in Scotland expected to host their first launches by 2025. In total, the UK is currently developing seven spaceports, positioning itself as a launch leader in Europe.

The UK is also at the forefront of satellite development, ranking among the top five countries with the most registered operational satellites in orbit. Recent government investments have further strengthened the UK's space industry, with initiatives like the Space Clusters Infrastructure Fund aimed at boosting the economy, developing advanced skills, and creating jobs within the sector.

One notable beneficiary of this fund is Welsh company Space Forge, which secured £7.9 million at the end of last year to establish a National Microgravity Research Centre. Space Forge specialises in in-space manufacturing (ISM), utilising the unique conditions of Earth's orbit to produce advanced materials—such as those used in semiconductors—and then returning them to Earth. Just last week, Space Forge announced the opening of a new office in Florida, near the Kennedy Space Center, to help revolutionise the US semiconductor market.

This move comes in the wake of the Biden Administration’s 2022 US CHIPS Act, which aims to strengthen domestic semiconductor research and production. Space Forge is actively recruiting for a ‘Head of Semiconductors’ in the US to support this effort.

In addition to growing its space economy, the UK is fostering international collaboration. In August 2023, the UK Space Agency announced the first recipients of its International Bilateral Fund, a program designed to strengthen global partnerships. Since then, the fund has supported projects with the USA, Australia, Japan, Canada, Germany, Singapore, the UAE, Bahrain, and others. This year, the fund received an additional £13 million to continue expanding these partnerships.

Like India, the UK is emerging as a vital player in space activity and collaboration. Joint efforts between nations will be essential not only for driving innovation, technology transfer, and knowledge sharing but also for ensuring that cooperation remains the foundation of peaceful space development.

ESA's Ariane-6 (Image: ESA - S. Corvaja)

How can legacy agencies keep pace in an ever-competitive space economy?

While the UK aims to lead in building a new European space architecture, Sinead O’Sullivan, writing in a recent Financial Times op-ed, highlights challenges facing both NASA and ESA. Her analysis draws from two reports—one by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and another by former European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi on European competitiveness.

O’Sullivan argues that both NASA and ESA, as large, publicly funded institutions, struggle to adapt quickly to modern economic and political realities (FT, 2024). NASA has increasingly turned to private companies, as seen with the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, but in doing so, it has lost talented engineers and scientists to the private sector. ESA, by contrast, has failed to attract enough private sector support.

O’Sullivan points to the launch sector as an example, where ESA's long-awaited Ariane-6 rocket has been delivered at a high cost for a vehicle that lacks reusability—a key factor in modern spaceflight efficiency.

As a solution, O’Sullivan proposes that NASA focus on long-term projects that serve humanity, while ESA should further incentivise private-sector collaboration and provide stronger support to space startups.

These strategies could prove crucial for both NASA and ESA, as the space industry is evolving at a rapid pace. Recent developments from nations like India and the UK demonstrate the determination of growing space nations, driven by nationally-funded programs that stimulate private innovation and growth.

Both agencies do of course see the immense value in the private sector and spearheading national programmes in space exploration. The US leads the way in utilising commercial technology for national space endeavours, such as through their Artemis programme, taking humans back to the Moon and establishing a permanent lunar infrastructure. ESA has only last year indicated its desire to utilise commercial launch services, and draw the curtain on the era of publicly-funded Ariane rockets, and also indicated their goal to establish a presence on the Moon within the next decade.

However, it will also be necessary to respond more quickly to the economic, political and geopolitical challenges that they now face in an expanding space industry.

Share this article