13 September 2024

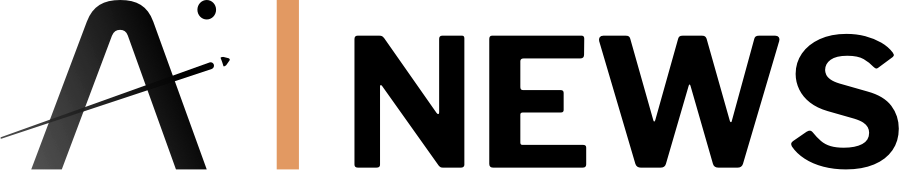

(Image: Intuitive Machines)

In April 2023, Japanese lunar exploration company iSpace watched as their HAKUTO-R Mission 1 lander crashed on the Moon, ending their attempt to become the first commercial entity to achieve a soft landing. Due to an anomaly during descent, the lander ran out of fuel, entered free-fall, and impacted the lunar surface. Demonstrating cost-effective lunar transport is difficult, with similar failed attempts from Astrobotic (US) and SpaceIL (Israel).

Undeterred, iSpace learned from the setback and announced Mission 2, scheduled for December. This mission will send the Resilience lunar lander and the European-built Tenacious micro rover, which will collect regolith samples and transfer ownership to NASA, a significant milestone for commercial lunar activity.

iSpace has also strengthened its expertise, forming a Lunar Advisory Board featuring former ESA, SpaceX, and NASA leaders.

Meanwhile, the US is racing to keep pace, following China’s successful Chang’e-6 mission in June. NASA is sending payloads with Intuitive Machines' second commercial mission, launching late this year or early next. This mission includes NASA’s Lunar Trailblazer orbiter to study water distribution and the Prime-1 drill to search for water ice.

The IM-2 mission will also carry the NASA-funded Micro-Nova Hopper, a rover designed to jump across the surface, detecting hydrogen. Mapping key resources is crucial for future lunar infrastructure.

Commercial innovation is key to US leadership. Seattle-based Interlune outlined plans to extract Helium-3 from the Moon, a potential fuel for nuclear fusion. However, some experts, like Professor Ian Crawford, University of London, are skeptical about the viability of Helium-3 for fusion reactors, citing its low abundance.

However, Interlune plans to mine small amounts, aiming to sell Helium-3 by the 2030s. Their 2027 mission aims to validate concentrations, followed by a 2029 mission to establish a pilot plant.

Though other resources, like water ice, may be more immediately valuable, China is also exploring Helium-3, with plans to develop a lunar magnetic launcher to return payloads to Earth.

(Image: Adobe)

China details lunar base project, India declares interest in Russia nuclear power solution

China is progressing with its plans for long-term lunar settlements. The Chang’e-7 mission, launching in 2026, aims to investigate lunar soil for water ice, followed by Chang’e-8 in 2028, which will conduct in-situ resource utilisation (ISRU) tests. Both missions are key steps toward establishing a permanent lunar base by 2035.

This week, Wu Weiren, chief designer of China’s lunar program, announced that the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) will be built in two phases: the initial version between 2030 and 2035, with a full-scale research station by 2050. Russia, a key partner, will provide a lunar nuclear power plant with a capacity of up to half a megawatt, ensuring energy supply during the 14-day lunar nights. According to The EurAsian Times, India has also expressed interest in this power plant, aligning with their goal of establishing a lunar base by 2050.

Collaboration between India, China, and Russia would add an interesting dynamic to international space relations. Two major "space blocs" are emerging: one led by the US under the Artemis Accords, and the other by China with the ILRS project. Last week, Senegal became the latest country to join the ILRS project, and other organisations have signed memorandums of understanding with China.

Although India has not joined the ILRS, working with Russia and China could help bridge the diplomatic gap with the US, as India is also part of the Artemis Accords. Similarly, UAE-based Orbital Space has partnered with China’s Deep Space Exploration Lab to provide technologies for missions that may support the ILRS. The UAE is also part of the Artemis Accords, suggesting that companies and organisations may help ease geopolitical tensions between space superpowers.

(Image: SpaceX)

First commercial spacewalk and Polaris Dawn mission sparks legal debate

Cooperation between all parties is more critical than ever as the space industry advances rapidly while legislation struggles to keep pace. This week, SpaceX launched the Polaris Dawn mission, marking the first-ever commercial spacewalk by billionaire Jared Isaacman and Sarah Gillis. While a historic milestone, it also reignited important legal questions about the expanding role of private companies in space exploration.

The mission was privately funded by Isaacman and operated by SpaceX, utilising a Crew Dragon spacecraft launched atop a Falcon-9 rocket. However, Article VI of the widely recognised UN Outer Space Treaty (OST) states that "States Parties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space… by non-governmental entities." In this instance, NASA and the U.S. government were not involved. When contacted by Al Jazeera, the U.S. Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) clarified that "under federal law, the FAA is prohibited from issuing regulations for commercial human spaceflight occupant safety."

With SpaceX solely responsible for the mission and crew, it raises the question: are we witnessing a disregard for long-standing international law, potentially setting dangerous precedents for future commercial space activities? The absence of direct government oversight in this case highlights the growing legal grey areas surrounding private-sector involvement in space exploration, particularly in relation to international treaties like the OST.

According to Ram Jakhu, former director of the Institute of Air and Space Law at McGill University, the U.S. is not violating any laws. He explains that, concerning governments' responsibility to oversee space activities as mandated by the Outer Space Treaty (OST), "there are no internationally binding regulations that clearly define this term, nor are there international technical standards or procedures to effectively enforce this obligation.”

Jakhu also noted that while rules need to be developed in the coming years, nations have “discretion to define the term(s)”. This ambiguity in the Outer Space Treaty remains a significant issue in new space exploration and will become increasingly urgent as companies take a leading role in utilising space resources and building infrastructure on other celestial bodies. In his book Who Owns The Moon (2024), A.C. Grayling argues that the “vagueness of expressions is deliberate” in the OST, as it is “key to achieving agreements in cases where competing interests are in play.”

Efforts to build transparency, and an expanded role for the private sector and civil society

The truth may be that the immense value placed on space exploration and its potential benefits, coupled with the rise of commercially-led space endeavours, is creating a critical need for clearer regulations and international cooperation.

This is evident from the growing political discourse on off-world resource extraction, such as the US House discussion in December last year. The discussion evolved into a partisan debate, with Greg Autry, a professor at Arizona State University's Thunderbird School of Global Management, stating that "any delay in America's development of space resources, no matter how well intended, will leave the field to that rapacious regime," referring to China.

NASA Chief Bill Nelson has also repeatedly warned about the competition with China, expressing concern that China might claim large portions of lunar territory “under the guise of scientific research.” It is believed that the U.S. intends to use the concept of “safety zones” within the Artemis Accords to secure resource-rich areas of the Moon, potentially navigating around Article II of the Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits the appropriation of the Moon and other celestial bodies. Geopolitical interests continue to drive distrust in outer space exploration.

This is not to say that efforts aren’t being made to address these issues. This year, at the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), an Action Team on Lunar Activities Consultation (ATLAC) was adopted and will be established in the coming years. Proposed by Romania, this mechanism aims to facilitate consultations to coordinate issues such as safety, interoperability, and sustainability.

A report from the Chair of the Working Group on the Status and Application of the Five United Nations Treaties on Outer Space of the Legal Subcommittee discussed the potential implementation of Article XI of the OST. This article could require States to submit information about their activities on celestial bodies like the Moon to the Secretary-General. An open repository for this information could enhance transparency and build confidence, but it remains to be seen how much data States and commercial entities would be willing to share.

There may also be a need for a greater role for commercial and non-governmental entities in law and policy-making. Clearer regulations would provide confidence for business activities and insurers, while also contributing to discussions on the peaceful and sustainable use of outer space, as outlined in the OST. At the COPUOS meeting, the committee recommended that “permanent observers inform the subcommittee of actions taken to build capacity in space law.” Observers of the committee include organisations, think tanks, and NGOs such as the Moon Village Association, Secure World Foundation, and the European Space Policy Institute.

While contributions from current observers are valued and essential to UN discussions, there may be a growing need for involvement from additional non-space entities, including representatives from industry. Some delegations suggested that the committee could benefit from incorporating research and experience from a broader range of non-state actors, such as the private sector.

Space technology is crucial in shaping our future and will be a significant topic at the upcoming UN Summit of the Future. The discussion will focus on how space technology can help achieve sustainability goals for humanity and the planet. Given its importance, it may be time to engage all stakeholders, including industry and civil society, in these conversations.

(Image: Adobe)

13 September 2024

iSpace planning for December Moon launch, China detail lunar base plans, and Polaris Dawn mission highlights serious legal questions - Space News Roundup

In April 2023, Japanese lunar exploration company iSpace watched as their HAKUTO-R Mission 1 lander crashed on the Moon, ending their attempt to become the first commercial entity to achieve a soft landing. Due to an anomaly during descent, the lander ran out of fuel, entered free-fall, and impacted the lunar surface. Demonstrating cost-effective lunar transport is difficult, with similar failed attempts from Astrobotic (US) and SpaceIL (Israel).

Undeterred, iSpace learned from the setback and announced Mission 2, scheduled for December. This mission will send the Resilience lunar lander and the European-built Tenacious micro rover, which will collect regolith samples and transfer ownership to NASA, a significant milestone for commercial lunar activity.

iSpace has also strengthened its expertise, forming a Lunar Advisory Board featuring former ESA, SpaceX, and NASA leaders.

Meanwhile, the US is racing to keep pace, following China’s successful Chang’e-6 mission in June. NASA is sending payloads with Intuitive Machines' second commercial mission, launching late this year or early next. This mission includes NASA’s Lunar Trailblazer orbiter to study water distribution and the Prime-1 drill to search for water ice.

The IM-2 mission will also carry the NASA-funded Micro-Nova Hopper, a rover designed to jump across the surface, detecting hydrogen. Mapping key resources is crucial for future lunar infrastructure.

Commercial innovation is key to US leadership. Seattle-based Interlune outlined plans to extract Helium-3 from the Moon, a potential fuel for nuclear fusion. However, some experts, like Professor Ian Crawford, University of London, are skeptical about the viability of Helium-3 for fusion reactors, citing its low abundance.

However, Interlune plans to mine small amounts, aiming to sell Helium-3 by the 2030s. Their 2027 mission aims to validate concentrations, followed by a 2029 mission to establish a pilot plant.

Though other resources, like water ice, may be more immediately valuable, China is also exploring Helium-3, with plans to develop a lunar magnetic launcher to return payloads to Earth.

(Image: Adobe)

China details lunar base project, India declares interest in Russia nuclear power solution

China is progressing with its plans for long-term lunar settlements. The Chang’e-7 mission, launching in 2026, aims to investigate lunar soil for water ice, followed by Chang’e-8 in 2028, which will conduct in-situ resource utilisation (ISRU) tests. Both missions are key steps toward establishing a permanent lunar base by 2035.

This week, Wu Weiren, chief designer of China’s lunar program, announced that the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) will be built in two phases: the initial version between 2030 and 2035, with a full-scale research station by 2050. Russia, a key partner, will provide a lunar nuclear power plant with a capacity of up to half a megawatt, ensuring energy supply during the 14-day lunar nights. According to The EurAsian Times, India has also expressed interest in this power plant, aligning with their goal of establishing a lunar base by 2050.

Collaboration between India, China, and Russia would add an interesting dynamic to international space relations. Two major "space blocs" are emerging: one led by the US under the Artemis Accords, and the other by China with the ILRS project. Last week, Senegal became the latest country to join the ILRS project, and other organisations have signed memorandums of understanding with China.

Although India has not joined the ILRS, working with Russia and China could help bridge the diplomatic gap with the US, as India is also part of the Artemis Accords. Similarly, UAE-based Orbital Space has partnered with China’s Deep Space Exploration Lab to provide technologies for missions that may support the ILRS. The UAE is also part of the Artemis Accords, suggesting that companies and organisations may help ease geopolitical tensions between space superpowers.

(Image: SpaceX)

First commercial spacewalk and Polaris Dawn mission sparks legal debate

Cooperation between all parties is more critical than ever as the space industry advances rapidly while legislation struggles to keep pace. This week, SpaceX launched the Polaris Dawn mission, marking the first-ever commercial spacewalk by billionaire Jared Isaacman and Sarah Gillis. While a historic milestone, it also reignited important legal questions about the expanding role of private companies in space exploration.

The mission was privately funded by Isaacman and operated by SpaceX, utilising a Crew Dragon spacecraft launched atop a Falcon-9 rocket. However, Article VI of the widely recognised UN Outer Space Treaty (OST) states that "States Parties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space… by non-governmental entities." In this instance, NASA and the U.S. government were not involved. When contacted by Al Jazeera, the U.S. Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) clarified that "under federal law, the FAA is prohibited from issuing regulations for commercial human spaceflight occupant safety."

With SpaceX solely responsible for the mission and crew, it raises the question: are we witnessing a disregard for long-standing international law, potentially setting dangerous precedents for future commercial space activities? The absence of direct government oversight in this case highlights the growing legal grey areas surrounding private-sector involvement in space exploration, particularly in relation to international treaties like the OST.

According to Ram Jakhu, former director of the Institute of Air and Space Law at McGill University, the U.S. is not violating any laws. He explains that, concerning governments' responsibility to oversee space activities as mandated by the Outer Space Treaty (OST), "there are no internationally binding regulations that clearly define this term, nor are there international technical standards or procedures to effectively enforce this obligation.”

Jakhu also noted that while rules need to be developed in the coming years, nations have “discretion to define the term(s)”. This ambiguity in the Outer Space Treaty remains a significant issue in new space exploration and will become increasingly urgent as companies take a leading role in utilising space resources and building infrastructure on other celestial bodies. In his book Who Owns The Moon (2024), A.C. Grayling argues that the “vagueness of expressions is deliberate” in the OST, as it is “key to achieving agreements in cases where competing interests are in play.”

Efforts to build transparency, and an expanded role for the private sector and civil society

The truth may be that the immense value placed on space exploration and its potential benefits, coupled with the rise of commercially-led space endeavours, is creating a critical need for clearer regulations and international cooperation.

This is evident from the growing political discourse on off-world resource extraction, such as the US House discussion in December last year. The discussion evolved into a partisan debate, with Greg Autry, a professor at Arizona State University's Thunderbird School of Global Management, stating that "any delay in America's development of space resources, no matter how well intended, will leave the field to that rapacious regime," referring to China.

NASA Chief Bill Nelson has also repeatedly warned about the competition with China, expressing concern that China might claim large portions of lunar territory “under the guise of scientific research.” It is believed that the U.S. intends to use the concept of “safety zones” within the Artemis Accords to secure resource-rich areas of the Moon, potentially navigating around Article II of the Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits the appropriation of the Moon and other celestial bodies. Geopolitical interests continue to drive distrust in outer space exploration.

This is not to say that efforts aren’t being made to address these issues. This year, at the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), an Action Team on Lunar Activities Consultation (ATLAC) was adopted and will be established in the coming years. Proposed by Romania, this mechanism aims to facilitate consultations to coordinate issues such as safety, interoperability, and sustainability.

A report from the Chair of the Working Group on the Status and Application of the Five United Nations Treaties on Outer Space of the Legal Subcommittee discussed the potential implementation of Article XI of the OST. This article could require States to submit information about their activities on celestial bodies like the Moon to the Secretary-General. An open repository for this information could enhance transparency and build confidence, but it remains to be seen how much data States and commercial entities would be willing to share.

There may also be a need for a greater role for commercial and non-governmental entities in law and policy-making. Clearer regulations would provide confidence for business activities and insurers, while also contributing to discussions on the peaceful and sustainable use of outer space, as outlined in the OST. At the COPUOS meeting, the committee recommended that “permanent observers inform the subcommittee of actions taken to build capacity in space law.” Observers of the committee include organisations, think tanks, and NGOs such as the Moon Village Association, Secure World Foundation, and the European Space Policy Institute.

While contributions from current observers are valued and essential to UN discussions, there may be a growing need for involvement from additional non-space entities, including representatives from industry. Some delegations suggested that the committee could benefit from incorporating research and experience from a broader range of non-state actors, such as the private sector.

Space technology is crucial in shaping our future and will be a significant topic at the upcoming UN Summit of the Future. The discussion will focus on how space technology can help achieve sustainability goals for humanity and the planet. Given its importance, it may be time to engage all stakeholders, including industry and civil society, in these conversations.

Share this article

13 September 2024

iSpace planning for December Moon launch, China detail lunar base plans, and Polaris Dawn mission highlights serious legal questions - Space News Roundup

(Image: Intuitive Machines)

In April 2023, Japanese lunar exploration company iSpace watched as their HAKUTO-R Mission 1 lander crashed on the Moon, ending their attempt to become the first commercial entity to achieve a soft landing. Due to an anomaly during descent, the lander ran out of fuel, entered free-fall, and impacted the lunar surface. Demonstrating cost-effective lunar transport is difficult, with similar failed attempts from Astrobotic (US) and SpaceIL (Israel).

Undeterred, iSpace learned from the setback and announced Mission 2, scheduled for December. This mission will send the Resilience lunar lander and the European-built Tenacious micro rover, which will collect regolith samples and transfer ownership to NASA, a significant milestone for commercial lunar activity.

iSpace has also strengthened its expertise, forming a Lunar Advisory Board featuring former ESA, SpaceX, and NASA leaders.

Meanwhile, the US is racing to keep pace, following China’s successful Chang’e-6 mission in June. NASA is sending payloads with Intuitive Machines' second commercial mission, launching late this year or early next. This mission includes NASA’s Lunar Trailblazer orbiter to study water distribution and the Prime-1 drill to search for water ice.

The IM-2 mission will also carry the NASA-funded Micro-Nova Hopper, a rover designed to jump across the surface, detecting hydrogen. Mapping key resources is crucial for future lunar infrastructure.

Commercial innovation is key to US leadership. Seattle-based Interlune outlined plans to extract Helium-3 from the Moon, a potential fuel for nuclear fusion. However, some experts, like Professor Ian Crawford, University of London, are skeptical about the viability of Helium-3 for fusion reactors, citing its low abundance.

However, Interlune plans to mine small amounts, aiming to sell Helium-3 by the 2030s. Their 2027 mission aims to validate concentrations, followed by a 2029 mission to establish a pilot plant.

Though other resources, like water ice, may be more immediately valuable, China is also exploring Helium-3, with plans to develop a lunar magnetic launcher to return payloads to Earth.

(Image: Adobe

China details lunar base project, India declares interest in Russia nuclear power solution

China is progressing with its plans for long-term lunar settlements. The Chang’e-7 mission, launching in 2026, aims to investigate lunar soil for water ice, followed by Chang’e-8 in 2028, which will conduct in-situ resource utilisation (ISRU) tests. Both missions are key steps toward establishing a permanent lunar base by 2035.

This week, Wu Weiren, chief designer of China’s lunar program, announced that the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) will be built in two phases: the initial version between 2030 and 2035, with a full-scale research station by 2050. Russia, a key partner, will provide a lunar nuclear power plant with a capacity of up to half a megawatt, ensuring energy supply during the 14-day lunar nights. According to The EurAsian Times, India has also expressed interest in this power plant, aligning with their goal of establishing a lunar base by 2050.

Collaboration between India, China, and Russia would add an interesting dynamic to international space relations. Two major "space blocs" are emerging: one led by the US under the Artemis Accords, and the other by China with the ILRS project. Last week, Senegal became the latest country to join the ILRS project, and other organisations have signed memorandums of understanding with China.

Although India has not joined the ILRS, working with Russia and China could help bridge the diplomatic gap with the US, as India is also part of the Artemis Accords. Similarly, UAE-based Orbital Space has partnered with China’s Deep Space Exploration Lab to provide technologies for missions that may support the ILRS. The UAE is also part of the Artemis Accords, suggesting that companies and organisations may help ease geopolitical tensions between space superpowers.

(Image: SpaceX)

First commercial spacewalk and Polaris Dawn mission sparks legal debate

Cooperation between all parties is more critical than ever as the space industry advances rapidly while legislation struggles to keep pace. This week, SpaceX launched the Polaris Dawn mission, marking the first-ever commercial spacewalk by billionaire Jared Isaacman and Sarah Gillis. While a historic milestone, it also reignited important legal questions about the expanding role of private companies in space exploration.

The mission was privately funded by Isaacman and operated by SpaceX, utilising a Crew Dragon spacecraft launched atop a Falcon-9 rocket. However, Article VI of the widely recognised UN Outer Space Treaty (OST) states that "States Parties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space… by non-governmental entities." In this instance, NASA and the U.S. government were not involved. When contacted by Al Jazeera, the U.S. Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) clarified that "under federal law, the FAA is prohibited from issuing regulations for commercial human spaceflight occupant safety."

With SpaceX solely responsible for the mission and crew, it raises the question: are we witnessing a disregard for long-standing international law, potentially setting dangerous precedents for future commercial space activities? The absence of direct government oversight in this case highlights the growing legal grey areas surrounding private-sector involvement in space exploration, particularly in relation to international treaties like the OST.

According to Ram Jakhu, former director of the Institute of Air and Space Law at McGill University, the U.S. is not violating any laws. He explains that, concerning governments' responsibility to oversee space activities as mandated by the Outer Space Treaty (OST), "there are no internationally binding regulations that clearly define this term, nor are there international technical standards or procedures to effectively enforce this obligation.”

Jakhu also noted that while rules need to be developed in the coming years, nations have “discretion to define the term(s)”. This ambiguity in the Outer Space Treaty remains a significant issue in new space exploration and will become increasingly urgent as companies take a leading role in utilising space resources and building infrastructure on other celestial bodies. In his book Who Owns The Moon (2024), A.C. Grayling argues that the “vagueness of expressions is deliberate” in the OST, as it is “key to achieving agreements in cases where competing interests are in play.”

Efforts to build transparency, and an expanded role for the private sector and civil society

The truth may be that the immense value placed on space exploration and its potential benefits, coupled with the rise of commercially-led space endeavours, is creating a critical need for clearer regulations and international cooperation.

This is evident from the growing political discourse on off-world resource extraction, such as the US House discussion in December last year. The discussion evolved into a partisan debate, with Greg Autry, a professor at Arizona State University's Thunderbird School of Global Management, stating that "any delay in America's development of space resources, no matter how well intended, will leave the field to that rapacious regime," referring to China.

NASA Chief Bill Nelson has also repeatedly warned about the competition with China, expressing concern that China might claim large portions of lunar territory “under the guise of scientific research.” It is believed that the U.S. intends to use the concept of “safety zones” within the Artemis Accords to secure resource-rich areas of the Moon, potentially navigating around Article II of the Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits the appropriation of the Moon and other celestial bodies. Geopolitical interests continue to drive distrust in outer space exploration.

This is not to say that efforts aren’t being made to address these issues. This year, at the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), an Action Team on Lunar Activities Consultation (ATLAC) was adopted and will be established in the coming years. Proposed by Romania, this mechanism aims to facilitate consultations to coordinate issues such as safety, interoperability, and sustainability.

A report from the Chair of the Working Group on the Status and Application of the Five United Nations Treaties on Outer Space of the Legal Subcommittee discussed the potential implementation of Article XI of the OST. This article could require States to submit information about their activities on celestial bodies like the Moon to the Secretary-General. An open repository for this information could enhance transparency and build confidence, but it remains to be seen how much data States and commercial entities would be willing to share.

There may also be a need for a greater role for commercial and non-governmental entities in law and policy-making. Clearer regulations would provide confidence for business activities and insurers, while also contributing to discussions on the peaceful and sustainable use of outer space, as outlined in the OST. At the COPUOS meeting, the committee recommended that “permanent observers inform the subcommittee of actions taken to build capacity in space law.” Observers of the committee include organisations, think tanks, and NGOs such as the Moon Village Association, Secure World Foundation, and the European Space Policy Institute.

While contributions from current observers are valued and essential to UN discussions, there may be a growing need for involvement from additional non-space entities, including representatives from industry. Some delegations suggested that the committee could benefit from incorporating research and experience from a broader range of non-state actors, such as the private sector.

Space technology is crucial in shaping our future and will be a significant topic at the upcoming UN Summit of the Future. The discussion will focus on how space technology can help achieve sustainability goals for humanity and the planet. Given its importance, it may be time to engage all stakeholders, including industry and civil society, in these conversations.

Share this article