12 January 2024

View from Astrobotic lander with Earth in top right (Image - Astrobotic)

“And if they fail, the next one is going to learn and succeed,” is what NASA deputy administrator Pam Melroy said to the BBC last month, while discussing the highly anticipated Astrobotic commercial lunar landing mission. The company carried out a successful launch on January 8, atop a new ULA Vulcan rocket, hoping to become the first private company to successfully land on the Moon.

However, a few hours after launch, Astrobotic announced that they had discovered a propellant leak on the vehicle, which has subsequently led them to conclude there this no chance of a soft landing on the Moon. They did go on to state that they “do still have enough propellant to continue to operate the vehicle as a spacecraft,” and were looking into now establishing some secondary mission objectives.

On Thursday the company added that they had successfully be able to provide power to, and receive data from none of the twenty payloads, and that there was enough propellant left for 48 hours of operations.

Most importantly, the mission can be used in order to collect valuable data for future missions, perhaps aligning with the SpaceX formula for success, “fail fast, learn faster”. NASA purchased services from Astrobotic under their Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) programme, whereby the agency doesn’t develop its own vehicles, but rather seeks to increase efficiency through purchasing transport through commercial partners.

With possibly four more commercial missions under the CLPS programme to set off this year (Intuitive Machines being next, launching mid-February), the lessons that can be learnt will only prove to be an integral part of the ongoing commercialisation of lunar exploration, and a key stepping stone towards our future in outer space.

Delays keep Artemis crewed missions ahead of China, but Chang’e lander coming this year

NASA also announced updates for its own lunar project, the Artemis missions, this week. Artemis-I launched back in November 2022, successfully travelling beyond the Moon, farther than any human-proof vehicle has ever gone, before returning back to Earth. It seen as a hugely successful step towards the US-led effort to return astronauts to the surface of the Moon for the first time in over 50 years.

However, the first crewed Artemis missions have now been delayed by a year. Artemis-II, which will take astronauts around the Moon and back again, will launch no sooner than September 2025, with Artemis-III (the first crewed landing mission) scheduled for a year later.

Similar to the constructive attitude shown in light of the Astrobotic Mission One setback, the Artemis delay presents NASA with an opportunity to learn from the data gathered from the Artemis-I mission, and also give SpaceX time to develop their Starship Human Landing System, and Axiom (US) to complete their next generation of spacesuits.

The delay also still keeps NASA years ahead of its competition in any race to send humans back to the Moon, with China planning their first crewed mission for 2030.

Furthermore, the US also scored another PR and strategic victory this week, as they announced that the UAE will be building the airlock for the planned Lunar Gateway, a lunar orbital space station that will act as a relay point for astronauts landing on the surface.

The Middle Eastern nation could rove to be a valuable partner, it being in the unique position of being part of both the US-led Artemis Accords and the China-led International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project.

China could reach Moon before US this year, South Korea expand space ambitions

While NASA may strive to maintain a positive outlook, and look forwards to a busy lunar launch cadence this year, they will also be fully aware of the competition they are facing from China in the near future.

The China National Space Administration (CNSA) announced this week that their Chang’e-6 spacecraft has arrived at their Space Launch Center in Hainan province, and anticipate a launch in the first half of this year.

They may still be behind the US, if the Intuitive Machines February mission goes to plan, and also Japan, with their SLIM lander set to arrive on the Moon on January 19. However, the Chang’e-6 mission aims to carry out a significant first; to collect and retrieve samples from the far side of the Moon. They also have the experience and expertise gained from their successful Chang’e-5 mission, launched back in 2020.

Learning about the composition of the lunar surface, and moreover the location of valuable resources such as water, is becoming utmost importance for leading space nations. Utilising such resources is a vital step towards establishing a sustained human presence, for in-situ resource utilisation, and eventually exploring the prospect of retrieving elements such as rare-earth materials and helium-3 for earthbound applications.

More nations are waking-up to this realisation, with South Korea this week announcing that they will establish their new space agency (KASA) in May this year, with plans for a lunar mission in 2032. While ambitious plans from newer space nations should be applauded, the sheer pace of launch cadence and innovation must be noted.

Within the next decade we are likely to see rapid development of the lunar economy, with competition for finite resources increasing. Add to this the lack and ambiguity of international space law surrounding the appropriation of lunar territory, and we are also likely to see a “race mentality” to set-in. It may be the case that any plans that any entities may have for lunar exploration should be expedited over the next few years, either alone or through international and/or commercial partnerships.

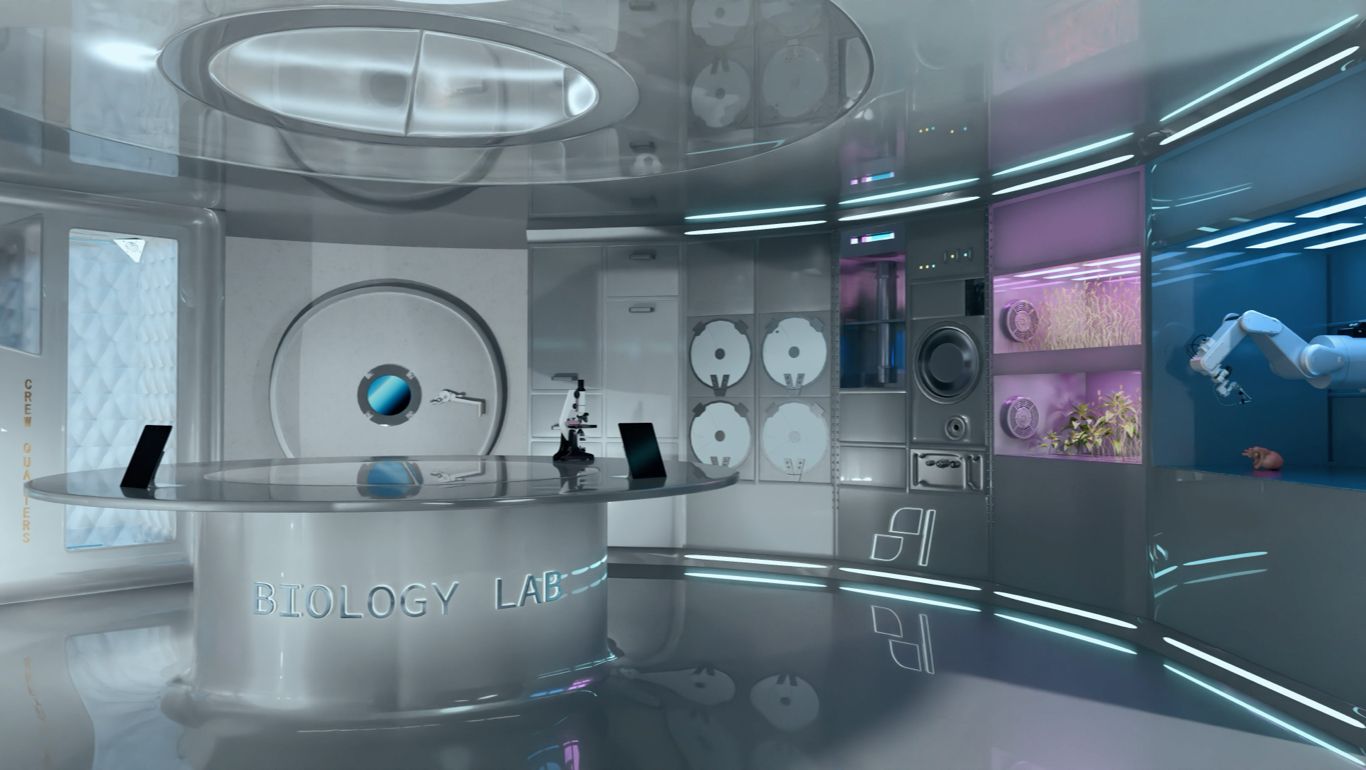

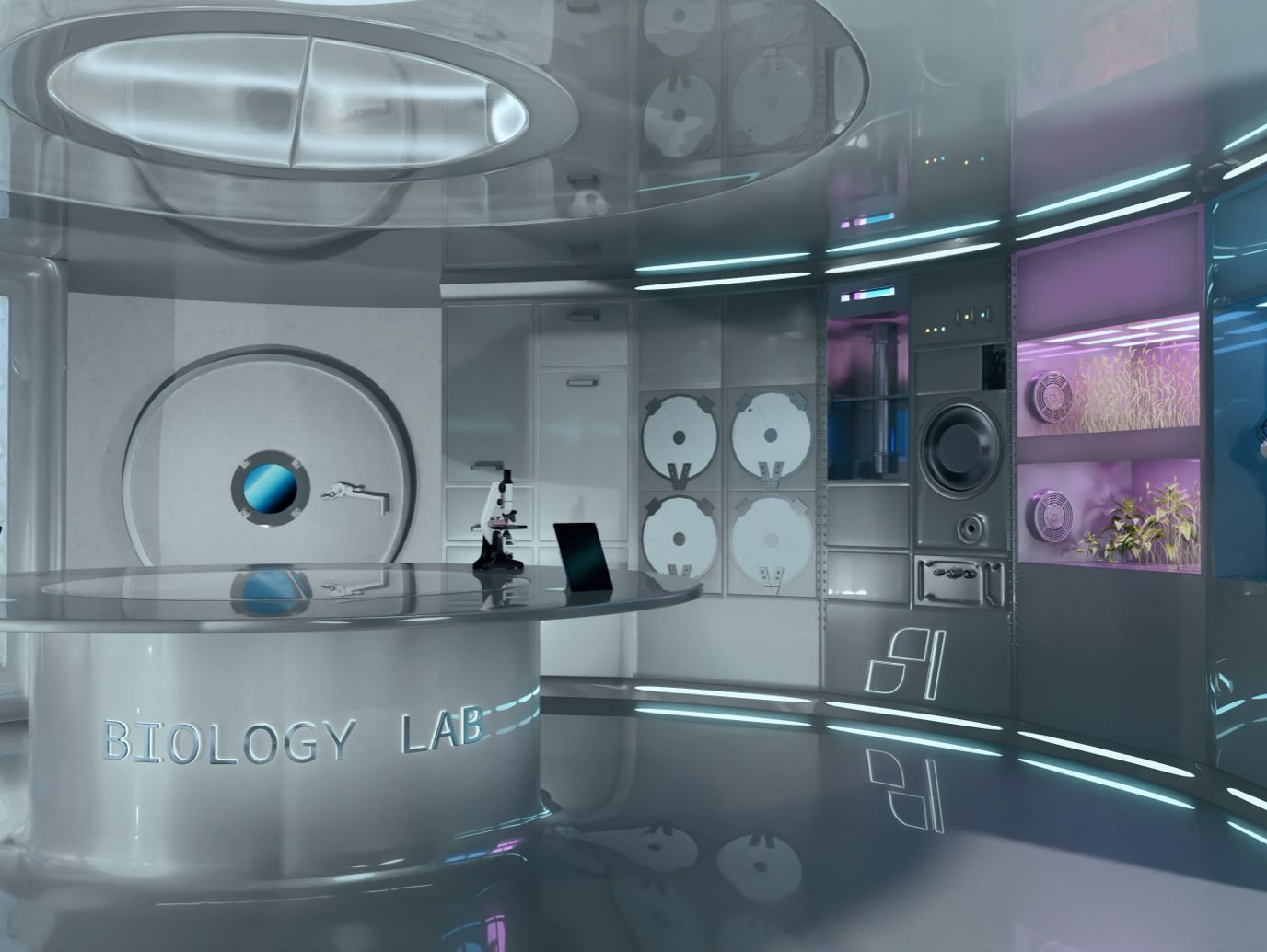

Render of inside Starlab (Image - Voyager/Starlab)

Commercial stations coming fast

Europe and ESA have quickly been waking up to this reality; that competition and innovation is rapidly increasing, and they do not want to miss out, including on the Moon.

In regards to establishing a European presence on the Moon, ESA head Josef Aschbacher said last year that Europe “should not miss the train”, as it did with chips, IT and other domains. European nations have also noted the huge success of US commercialisation, in particular when it comes to procuring launches from private companies, rather than developing their own.

As a result, the ESA head announced in November that the agency will be adopting a procurement model for launches, whereby the agency will act as anchor customers for European launch startups such as Orbit (UK), HyImpulse (Germany) and RFA (Germany).

It seems that Europe will also forge a similar path when it comes to maintaining crewed access to Earth-orbit, with the retirement of ISS anticipated at the end of the decade. On January 9, Airbus and Voyager Space announced the formation of Starlab Space, a new entity that will lead the development of their new Starlab commercial space station, slated for launch in 2028.

Jean-Marc Nasr, Head of Space Systems at Airbus, said that Starlab shows their “…commitment to reimagining the future of commercial space alongside Voyager, anchoring Starlab to European and American ambitions and pioneering the future of humanity in space.”

NASA have also added further funding towards the commercial station projects, providing Voyager with an additional $57.5 million under their Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations (CLD) programme. At the same time, Blue Origin, who are working on their Orbital Reef station in partnership with Sierra Space, received $42 million.

Whether in the areas of launch, space station development or lunar landing, the commercial sector is taking a firm lead.

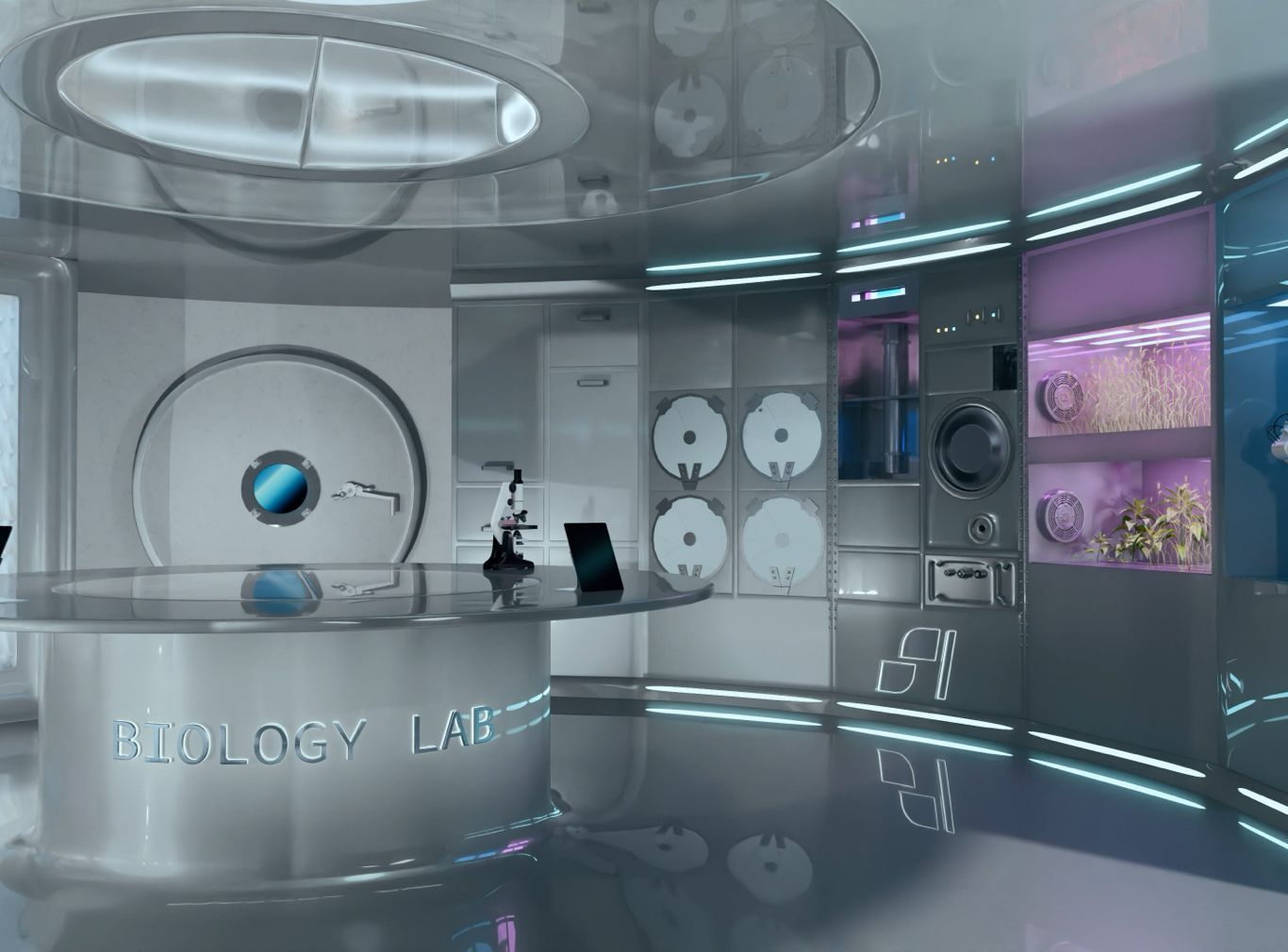

(Image - Adobe)

Sateliot 5G nano-satellites, D-Orbit secure significant funding

Earth-orbit and the overall orbital infrastructure is to continue its rapid expansion this year, through the growth of satellite constellations, providing increased access to communications, and more diverse applications such as in-space manufacturing.

Spanish satellite company, Sateliot, has this week announced that they have secured an additional €6 million funding towards the development of the first Low Earth Orbit (LEO) nanosatellites for providing 5G for IoT devices (Internet of Things). The company is set for significant growth this year, as it anticipates the launch of four new satellites, and the start of it commercial phase.

Additionally, Sateliot will look to secure series B funding in order to roll out the next phase of their constellation, made-up of 250 5G standard nanosatellites, with 64 set to be launched in the next 18 months.

Sateliot represent the ongoing growth and development of the New Space orbital infrastructure, with demand increasing for space-based connectivity, and through the development of tech such as direct-to-cell satellite connectivity.

DCUBED receive funding for ISAM, ESA push ISRU project

This year we also expect to see the continuing growth in the area of commercial in-space manufacturing, after witnessing some significant milestones last year. Space Forge (UK) attempted to launch their first orbital manufacturing satellite, but was lost with the failed Virgin Orbit launch, while Varda (US) successfully produced pharmaceutical products in-ornit for the first time.

This week, Germany-based DCUBED were awarded $1 million by the Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, under the Bavarian Space Research Programme. The funding will be used towards the development and demonstration of the in-space manufacturing of support structures for satellite solar panels. Producing these in-situ would eliminate the need to launch them from Earth, significantly cutting costs. It would also reduce the need for unfolding mechanisms, currently needed for the panels to survive launch stresses.

The German Aerospace Center (DLR) have also been exploring the use of in-space manufacturing, but for establishing power solutions on the Moon. “SoMo” is a project that will explore using lunar regolith to produce solar cells, and could build towards Europe’s ambition of establishing a lunar base in future. Blue Origin have been working on a very similar idea, named “Blue Alchemist, using electrolysis to create molten regolith to extract iron, silicon and aluminium.

With heightening interest in lunar exploration, and growing notion of a lunar race, we can also expect to see growth in the area of resource extraction and utilisation as well.

Our future in space

View from Astrobotic lander with Earth in top right (Image - Astrobotic)

12 January 2024

Astrobotic learn lessons from first mission, commercial space stations advancing, NASA delay Artemis - Space News Roundup

“And if they fail, the next one is going to learn and succeed,” is what NASA deputy administrator Pam Melroy said to the BBC last month, while discussing the highly anticipated Astrobotic commercial lunar landing mission. The company carried out a successful launch on January 8, atop a new ULA Vulcan rocket, hoping to become the first private company to successfully land on the Moon.

However, a few hours after launch, Astrobotic announced that they had discovered a propellant leak on the vehicle, which has subsequently led them to conclude there this no chance of a soft landing on the Moon. They did go on to state that they “do still have enough propellant to continue to operate the vehicle as a spacecraft,” and were looking into now establishing some secondary mission objectives.

On Thursday the company added that they had successfully be able to provide power to, and receive data from none of the twenty payloads, and that there was enough propellant left for 48 hours of operations.

Most importantly, the mission can be used in order to collect valuable data for future missions, perhaps aligning with the SpaceX formula for success, “fail fast, learn faster”. NASA purchased services from Astrobotic under their Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) programme, whereby the agency doesn’t develop its own vehicles, but rather seeks to increase efficiency through purchasing transport through commercial partners.

With possibly four more commercial missions under the CLPS programme to set off this year (Intuitive Machines being next, launching mid-February), the lessons that can be learnt will only prove to be an integral part of the ongoing commercialisation of lunar exploration, and a key stepping stone towards our future in outer space.

Delays keep Artemis crewed missions ahead of China, but Chang’e lander coming this year

NASA also announced updates for its own lunar project, the Artemis missions, this week. Artemis-I launched back in November 2022, successfully travelling beyond the Moon, farther than any human-proof vehicle has ever gone, before returning back to Earth. It seen as a hugely successful step towards the US-led effort to return astronauts to the surface of the Moon for the first time in over 50 years.

However, the first crewed Artemis missions have now been delayed by a year. Artemis-II, which will take astronauts around the Moon and back again, will launch no sooner than September 2025, with Artemis-III (the first crewed landing mission) scheduled for a year later.

Similar to the constructive attitude shown in light of the Astrobotic Mission One setback, the Artemis delay presents NASA with an opportunity to learn from the data gathered from the Artemis-I mission, and also give SpaceX time to develop their Starship Human Landing System, and Axiom (US) to complete their next generation of spacesuits.

The delay also still keeps NASA years ahead of its competition in any race to send humans back to the Moon, with China planning their first crewed mission for 2030.

Furthermore, the US also scored another PR and strategic victory this week, as they announced that the UAE will be building the airlock for the planned Lunar Gateway, a lunar orbital space station that will act as a relay point for astronauts landing on the surface.

The Middle Eastern nation could rove to be a valuable partner, it being in the unique position of being part of both the US-led Artemis Accords and the China-led International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project.

China could reach Moon before US this year, South Korea expand space ambitions

While NASA may strive to maintain a positive outlook, and look forwards to a busy lunar launch cadence this year, they will also be fully aware of the competition they are facing from China in the near future.

The China National Space Administration (CNSA) announced this week that their Chang’e-6 spacecraft has arrived at their Space Launch Center in Hainan province, and anticipate a launch in the first half of this year.

They may still be behind the US, if the Intuitive Machines February mission goes to plan, and also Japan, with their SLIM lander set to arrive on the Moon on January 19. However, the Chang’e-6 mission aims to carry out a significant first; to collect and retrieve samples from the far side of the Moon. They also have the experience and expertise gained from their successful Chang’e-5 mission, launched back in 2020.

Learning about the composition of the lunar surface, and moreover the location of valuable resources such as water, is becoming utmost importance for leading space nations. Utilising such resources is a vital step towards establishing a sustained human presence, for in-situ resource utilisation, and eventually exploring the prospect of retrieving elements such as rare-earth materials and helium-3 for earthbound applications.

More nations are waking-up to this realisation, with South Korea this week announcing that they will establish their new space agency (KASA) in May this year, with plans for a lunar mission in 2032. While ambitious plans from newer space nations should be applauded, the sheer pace of launch cadence and innovation must be noted.

Within the next decade we are likely to see rapid development of the lunar economy, with competition for finite resources increasing. Add to this the lack and ambiguity of international space law surrounding the appropriation of lunar territory, and we are also likely to see a “race mentality” to set-in. It may be the case that any plans that any entities may have for lunar exploration should be expedited over the next few years, either alone or through international and/or commercial partnerships.

Render of inside Starlab (Image - Voyager/Starlab)

Commercial stations coming fast

Europe and ESA have quickly been waking up to this reality; that competition and innovation is rapidly increasing, and they do not want to miss out, including on the Moon.

In regards to establishing a European presence on the Moon, ESA head Josef Aschbacher said last year that Europe “should not miss the train”, as it did with chips, IT and other domains. European nations have also noted the huge success of US commercialisation, in particular when it comes to procuring launches from private companies, rather than developing their own.

As a result, the ESA head announced in November that the agency will be adopting a procurement model for launches, whereby the agency will act as anchor customers for European launch startups such as Orbit (UK), HyImpulse (Germany) and RFA (Germany).

It seems that Europe will also forge a similar path when it comes to maintaining crewed access to Earth-orbit, with the retirement of ISS anticipated at the end of the decade. On January 9, Airbus and Voyager Space announced the formation of Starlab Space, a new entity that will lead the development of their new Starlab commercial space station, slated for launch in 2028.

Jean-Marc Nasr, Head of Space Systems at Airbus, said that Starlab shows their “…commitment to reimagining the future of commercial space alongside Voyager, anchoring Starlab to European and American ambitions and pioneering the future of humanity in space.”

NASA have also added further funding towards the commercial station projects, providing Voyager with an additional $57.5 million under their Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations (CLD) programme. At the same time, Blue Origin, who are working on their Orbital Reef station in partnership with Sierra Space, received $42 million.

Whether in the areas of launch, space station development or lunar landing, the commercial sector is taking a firm lead.

(Image - Adobe)

Sateliot 5G nano-satellites, D-Orbit secure significant funding

Earth-orbit and the overall orbital infrastructure is to continue its rapid expansion this year, through the growth of satellite constellations, providing increased access to communications, and more diverse applications such as in-space manufacturing.

Spanish satellite company, Sateliot, has this week announced that they have secured an additional €6 million funding towards the development of the first Low Earth Orbit (LEO) nanosatellites for providing 5G for IoT devices (Internet of Things). The company is set for significant growth this year, as it anticipates the launch of four new satellites, and the start of it commercial phase.

Additionally, Sateliot will look to secure series B funding in order to roll out the next phase of their constellation, made-up of 250 5G standard nanosatellites, with 64 set to be launched in the next 18 months.

Sateliot represent the ongoing growth and development of the New Space orbital infrastructure, with demand increasing for space-based connectivity, and through the development of tech such as direct-to-cell satellite connectivity.

DCUBED receive funding for ISAM, ESA push ISRU project

This year we also expect to see the continuing growth in the area of commercial in-space manufacturing, after witnessing some significant milestones last year. Space Forge (UK) attempted to launch their first orbital manufacturing satellite, but was lost with the failed Virgin Orbit launch, while Varda (US) successfully produced pharmaceutical products in-ornit for the first time.

This week, Germany-based DCUBED were awarded $1 million by the Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, under the Bavarian Space Research Programme. The funding will be used towards the development and demonstration of the in-space manufacturing of support structures for satellite solar panels. Producing these in-situ would eliminate the need to launch them from Earth, significantly cutting costs. It would also reduce the need for unfolding mechanisms, currently needed for the panels to survive launch stresses.

The German Aerospace Center (DLR) have also been exploring the use of in-space manufacturing, but for establishing power solutions on the Moon. “SoMo” is a project that will explore using lunar regolith to produce solar cells, and could build towards Europe’s ambition of establishing a lunar base in future. Blue Origin have been working on a very similar idea, named “Blue Alchemist, using electrolysis to create molten regolith to extract iron, silicon and aluminium.

With heightening interest in lunar exploration, and growing notion of a lunar race, we can also expect to see growth in the area of resource extraction and utilisation as well.

Share this article

12 January 2024

Astrobotic learn lessons from first mission, commercial space stations advancing, NASA delay Artemis - Space News Roundup

View from Astrobotic lander with Earth in top right (Image - Astrobotic)

“And if they fail, the next one is going to learn and succeed,” is what NASA deputy administrator Pam Melroy said to the BBC last month, while discussing the highly anticipated Astrobotic commercial lunar landing mission. The company carried out a successful launch on January 8, atop a new ULA Vulcan rocket, hoping to become the first private company to successfully land on the Moon.

However, a few hours after launch, Astrobotic announced that they had discovered a propellant leak on the vehicle, which has subsequently led them to conclude there this no chance of a soft landing on the Moon. They did go on to state that they “do still have enough propellant to continue to operate the vehicle as a spacecraft,” and were looking into now establishing some secondary mission objectives.

On Thursday the company added that they had successfully be able to provide power to, and receive data from none of the twenty payloads, and that there was enough propellant left for 48 hours of operations.

Most importantly, the mission can be used in order to collect valuable data for future missions, perhaps aligning with the SpaceX formula for success, “fail fast, learn faster”. NASA purchased services from Astrobotic under their Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) programme, whereby the agency doesn’t develop its own vehicles, but rather seeks to increase efficiency through purchasing transport through commercial partners.

With possibly four more commercial missions under the CLPS programme to set off this year (Intuitive Machines being next, launching mid-February), the lessons that can be learnt will only prove to be an integral part of the ongoing commercialisation of lunar exploration, and a key stepping stone towards our future in outer space.

Delays keep Artemis crewed missions ahead of China, but Chang’e lander coming this year

NASA also announced updates for its own lunar project, the Artemis missions, this week. Artemis-I launched back in November 2022, successfully travelling beyond the Moon, farther than any human-proof vehicle has ever gone, before returning back to Earth. It seen as a hugely successful step towards the US-led effort to return astronauts to the surface of the Moon for the first time in over 50 years.

However, the first crewed Artemis missions have now been delayed by a year. Artemis-II, which will take astronauts around the Moon and back again, will launch no sooner than September 2025, with Artemis-III (the first crewed landing mission) scheduled for a year later.

Similar to the constructive attitude shown in light of the Astrobotic Mission One setback, the Artemis delay presents NASA with an opportunity to learn from the data gathered from the Artemis-I mission, and also give SpaceX time to develop their Starship Human Landing System, and Axiom (US) to complete their next generation of spacesuits.

The delay also still keeps NASA years ahead of its competition in any race to send humans back to the Moon, with China planning their first crewed mission for 2030.

Furthermore, the US also scored another PR and strategic victory this week, as they announced that the UAE will be building the airlock for the planned Lunar Gateway, a lunar orbital space station that will act as a relay point for astronauts landing on the surface.

The Middle Eastern nation could rove to be a valuable partner, it being in the unique position of being part of both the US-led Artemis Accords and the China-led International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project.

China could reach Moon before US this year, South Korea expand space ambitions

While NASA may strive to maintain a positive outlook, and look forwards to a busy lunar launch cadence this year, they will also be fully aware of the competition they are facing from China in the near future.

The China National Space Administration (CNSA) announced this week that their Chang’e-6 spacecraft has arrived at their Space Launch Center in Hainan province, and anticipate a launch in the first half of this year.

They may still be behind the US, if the Intuitive Machines February mission goes to plan, and also Japan, with their SLIM lander set to arrive on the Moon on January 19. However, the Chang’e-6 mission aims to carry out a significant first; to collect and retrieve samples from the far side of the Moon. They also have the experience and expertise gained from their successful Chang’e-5 mission, launched back in 2020.

Learning about the composition of the lunar surface, and moreover the location of valuable resources such as water, is becoming utmost importance for leading space nations. Utilising such resources is a vital step towards establishing a sustained human presence, for in-situ resource utilisation, and eventually exploring the prospect of retrieving elements such as rare-earth materials and helium-3 for earthbound applications.

More nations are waking-up to this realisation, with South Korea this week announcing that they will establish their new space agency (KASA) in May this year, with plans for a lunar mission in 2032. While ambitious plans from newer space nations should be applauded, the sheer pace of launch cadence and innovation must be noted.

Within the next decade we are likely to see rapid development of the lunar economy, with competition for finite resources increasing. Add to this the lack and ambiguity of international space law surrounding the appropriation of lunar territory, and we are also likely to see a “race mentality” to set-in. It may be the case that any plans that any entities may have for lunar exploration should be expedited over the next few years, either alone or through international and/or commercial partnerships.

Render of inside Starlab (Image - Voyager/Starlab)

Commercial stations coming fast

Europe and ESA have quickly been waking up to this reality; that competition and innovation is rapidly increasing, and they do not want to miss out, including on the Moon.

In regards to establishing a European presence on the Moon, ESA head Josef Aschbacher said last year that Europe “should not miss the train”, as it did with chips, IT and other domains. European nations have also noted the huge success of US commercialisation, in particular when it comes to procuring launches from private companies, rather than developing their own.

As a result, the ESA head announced in November that the agency will be adopting a procurement model for launches, whereby the agency will act as anchor customers for European launch startups such as Orbit (UK), HyImpulse (Germany) and RFA (Germany).

It seems that Europe will also forge a similar path when it comes to maintaining crewed access to Earth-orbit, with the retirement of ISS anticipated at the end of the decade. On January 9, Airbus and Voyager Space announced the formation of Starlab Space, a new entity that will lead the development of their new Starlab commercial space station, slated for launch in 2028.

Jean-Marc Nasr, Head of Space Systems at Airbus, said that Starlab shows their “…commitment to reimagining the future of commercial space alongside Voyager, anchoring Starlab to European and American ambitions and pioneering the future of humanity in space.”

NASA have also added further funding towards the commercial station projects, providing Voyager with an additional $57.5 million under their Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations (CLD) programme. At the same time, Blue Origin, who are working on their Orbital Reef station in partnership with Sierra Space, received $42 million.

Whether in the areas of launch, space station development or lunar landing, the commercial sector is taking a firm lead.

(Image - Adobe)

Sateliot 5G nano-satellites, D-Orbit secure significant funding

Earth-orbit and the overall orbital infrastructure is to continue its rapid expansion this year, through the growth of satellite constellations, providing increased access to communications, and more diverse applications such as in-space manufacturing.

Spanish satellite company, Sateliot, has this week announced that they have secured an additional €6 million funding towards the development of the first Low Earth Orbit (LEO) nanosatellites for providing 5G for IoT devices (Internet of Things). The company is set for significant growth this year, as it anticipates the launch of four new satellites, and the start of it commercial phase.

Additionally, Sateliot will look to secure series B funding in order to roll out the next phase of their constellation, made-up of 250 5G standard nanosatellites, with 64 set to be launched in the next 18 months.

Sateliot represent the ongoing growth and development of the New Space orbital infrastructure, with demand increasing for space-based connectivity, and through the development of tech such as direct-to-cell satellite connectivity.

DCUBED receive funding for ISAM, ESA push ISRU project

This year we also expect to see the continuing growth in the area of commercial in-space manufacturing, after witnessing some significant milestones last year. Space Forge (UK) attempted to launch their first orbital manufacturing satellite, but was lost with the failed Virgin Orbit launch, while Varda (US) successfully produced pharmaceutical products in-ornit for the first time.

This week, Germany-based DCUBED were awarded $1 million by the Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, under the Bavarian Space Research Programme. The funding will be used towards the development and demonstration of the in-space manufacturing of support structures for satellite solar panels. Producing these in-situ would eliminate the need to launch them from Earth, significantly cutting costs. It would also reduce the need for unfolding mechanisms, currently needed for the panels to survive launch stresses.

The German Aerospace Center (DLR) have also been exploring the use of in-space manufacturing, but for establishing power solutions on the Moon. “SoMo” is a project that will explore using lunar regolith to produce solar cells, and could build towards Europe’s ambition of establishing a lunar base in future. Blue Origin have been working on a very similar idea, named “Blue Alchemist, using electrolysis to create molten regolith to extract iron, silicon and aluminium.

With heightening interest in lunar exploration, and growing notion of a lunar race, we can also expect to see growth in the area of resource extraction and utilisation as well.

Share this article

External Links

This Week

News articles posted here are not property of ANASDA GmbH and belong to their respected owners. Postings here are external links only.