10 November 2023

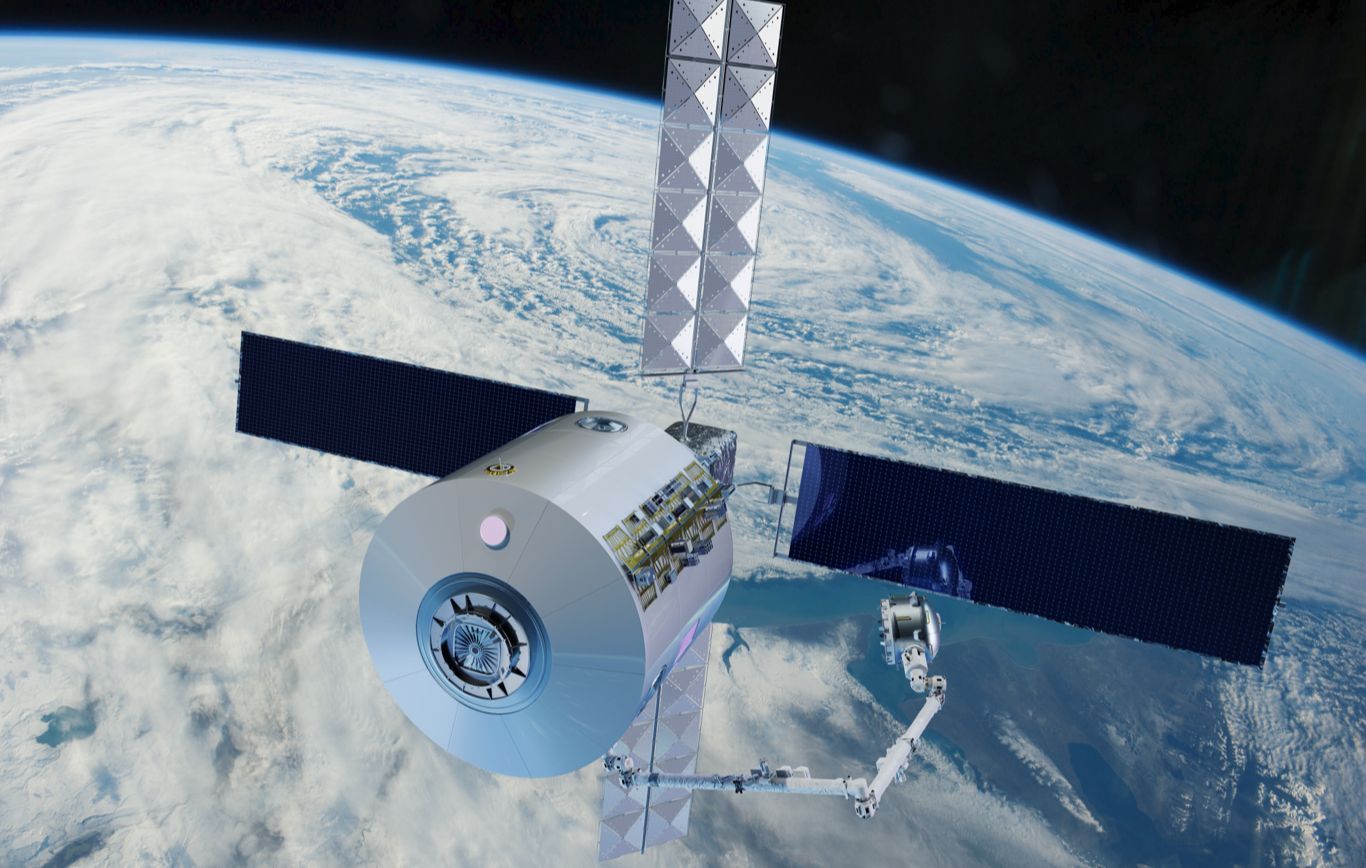

Illustration of Starlab's commercial station (Starlab/Voyager)

This week SpaceX launched their 80th mission of the year, already outnumbering their 2022 total of 61, signifying the astonishing success of the commercialisation of spaceflight. We are now beginning to see other players looking to replicate this success, such as the successful launch and landing of iSpace’s (China) Hyperbola-2Y single-stage last week. iSpace are using their vehicle to replicate the SpaceX workhorse, Falcon-9.

Sierra Space are also looking to ready themselves to enter the commercial space launch market with the completion of their Dream Chaser spaceplane. The vehicle, named Tenacity, is designed to ferry cargo to and from the ISS and will carry out its first launch maybe sometime next spring, using United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket.

Sierra are representative of just the latest piece of innovative spaceflight technology coming from the US commercial sector and represent the overall success of the model whereby national launches are now purchased rather than developed by national agencies.

As well as China looking to emulate this success, Europe appears to be finally getting on-board.

Europe switches to US model

Representatives from 22 European Space Agency nations came to an agreement this Monday to address the lack of independant European access to space, moving from a traditional, government-funded approach, to a commercial model, whereby ESA will look to buy services “as an anchor customer,” according to ESA head, Josef Aschbacher.

He went on to say that “I think it is fair to say today is a very successful day for space in Europe," but admitted that to will still take some time for the European launch market to mature and be in a position to provide heavy-launches. A number of smaller launch vehicles are lining-up for their maiden launches, from companies such as Skyrora (UK), Orbex (UK), Isar Aerospace (Germany).

One German company that has been the recipient of recent government support is Rocket Factory Augsburg, who have been given more funding through the ESA Boost! Programme (designed to support European launch startups). The funding is to support development of their vehicle, RFA One, at sites in Portugal, Germany and the UK. RFA One is a three-stage orbital vehicle, due to launch for the first time from Saxavord, Scotland, in April 2024.

Europe open launch sites, look to commercial cargo programme

Europe is set to become a hive of launch activity in the near future with launch sites opening-up across the UK (such as Saxavord), in Sweden and most recently, Norway. This week the Crown Prince of Norway opened what is billed as “the first operational orbital spaceport in Europe”, in Andøya. Germany’s Isar Aerospace will have exclusive access to the site for the launch of their two-stage Spectrum launch vehicle, but with no set launch date as of yet.

ESA aren’t only looking at building a commercialised model for launches, but this week also announced their intern to start a commercial cargo programme. The agency will begin a competition in order to source commercial vehicles to transport cargo to and from the ISS (and later newer stations), similar to the function of Sierra Space’s Dream Chaser, or the highly successful SpaceX Dragon Cargo.

It is still the early stages, but the ESA head said that “study contracts’ may be awarded to two or three companies at first, with the project later expanding under new funding arrangements from 2025.

Interestingly, this week Airbus have signed an agreement with Voyager Space (US) to explore the potential use of their Starlab commercial space station once the ISS is retired. The study will look into how the station can give Europe continued access to space, for crewed missions and scientific research. The station is currently expected to launch in 2028.

We are seeing Europe making a strong case for commercialisation, observing the roaring success in the US. Furthermore, considering ESA’s renewed energy and determination to “not miss the train” on the growing lunar economy, it seems that European space commercialisation may not end with only launch and orbital vehicles, but perhaps eventually extend to launder landing technology and resource utilisation.

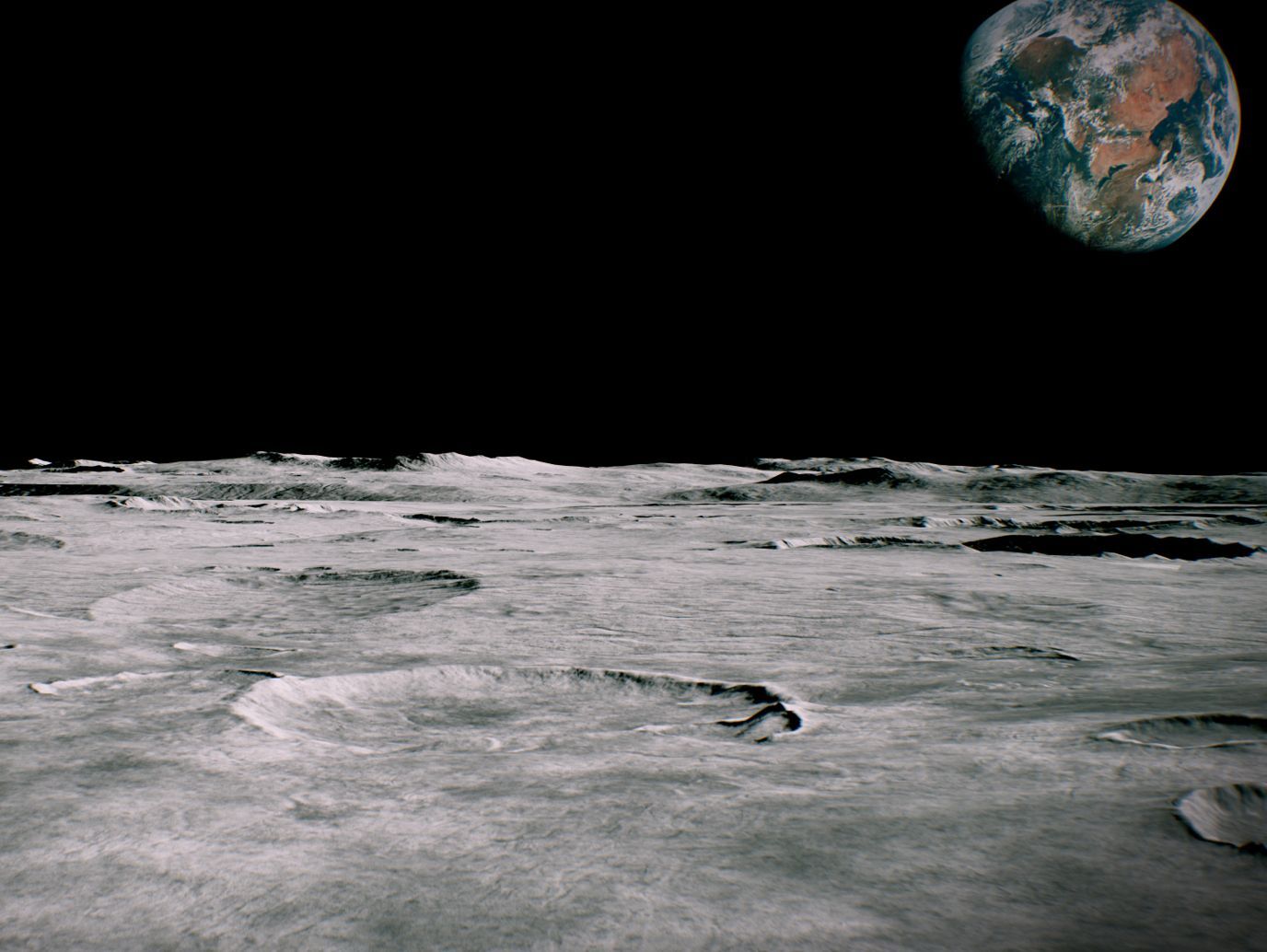

Lunar surface to become hive of activity (Adobe)

Türkiye to the Moon and input sought on resource utilisation and mining

As well as ESA, Türkiye have become the latest nation to set their eyes on the Moon. As part of their Lunar Research Program the nation looks to send its own spacecraft by 2026.

In the first stage of the programme, known as AYAP-1 (Lunar Research Program Project 1), they will send a spacecraft to explore the Moon from orbit. In the second stage, named AYAP-2, will look to land a rover on the surface.

In 2021, president Erdoğan unveiled 10-year Turkish space programme, looking to make the nation compete on the world stage.

Australia will also stake their claim in future of lunar exploration, adding their SPIDER (Seismic Payload for Interplanetary Discovery, Exploration, and Research) as payload on Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost lander, due to head to the far side of the Moon in 2026.

SPIDER will be used to collect seismic data from the lunar surface, with data ultimately being used to understand the geology of the lunar subsurface and the presence of water. Furthermore, the mission is part of the Australian Space Agency’s “Moon to Mars initiative”, looking to use the Moon as a launchpad to Mars.

Moreover, we are again seeing an increasing interest in the future of the lunar economy, looking towards building an infrastructure for permanent habitation and resource extraction.

NASA and Canadian company look to mine lunar resources

Following this charge, NGen, Canada’s industry-led, non-profit organization leading Canada’s Global Innovation Cluster for Advanced Manufacturing, has launched its Moonshot 4 Mining, Minerals and Manufacturing (M4M3) initiative. The programme is aimed at supporting development of in-situ resource utilisation (ISRU) for both lunar and terrestrial applications.

Additionally, the M4M3 programme will build on the technology required to establish a permanent human presence on the Moon, building on Canada’s heritage in robotics, additive manufacturing and tech. NGen will receive financial support from the Canadian Space Agency and open calls for projects in the areas of mining, critical minerals and manufacturing.

NASA are also looking to support the development of ISRU technologies and on November 6th “issued a Request for Information (RFI) on Nov. 6 to formulate its future Lunar Infrastructure Foundational Technologies (LIFT-1) demonstration” (NASA). LIFT-1 is to demonstrate technologies capable of extracting oxygen from lunar soil, leading to eventual production and storage of oxygen on the Moon.

There is clear pattern emerging, which is that of established and new space nations now looking closer at the development of the lunar infrastructure. Türkiye and ESA maybe the latest to look towards the Moon, but we can expect more to come.

Our future in space

Illustration of Starlab's commercial station (Starlab/Voyager)

10 November 2023

Europe Embraces US Commercial Space Strategy as Türkiye Sets Sights on Moon Mission - Space News Roundup

This week SpaceX launched their 80th mission of the year, already outnumbering their 2022 total of 61, signifying the astonishing success of the commercialisation of spaceflight. We are now beginning to see other players looking to replicate this success, such as the successful launch and landing of iSpace’s (China) Hyperbola-2Y single-stage last week. iSpace are using their vehicle to replicate the SpaceX workhorse, Falcon-9.

Sierra Space are also looking to ready themselves to enter the commercial space launch market with the completion of their Dream Chaser spaceplane. The vehicle, named Tenacity, is designed to ferry cargo to and from the ISS and will carry out its first launch maybe sometime next spring, using United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket.

Sierra are representative of just the latest piece of innovative spaceflight technology coming from the US commercial sector and represent the overall success of the model whereby national launches are now purchased rather than developed by national agencies.

As well as China looking to emulate this success, Europe appears to be finally getting on-board.

Europe switches to US model

Representatives from 22 European Space Agency nations came to an agreement this Monday to address the lack of independant European access to space, moving from a traditional, government-funded approach, to a commercial model, whereby ESA will look to buy services “as an anchor customer,” according to ESA head, Josef Aschbacher.

He went on to say that “I think it is fair to say today is a very successful day for space in Europe," but admitted that to will still take some time for the European launch market to mature and be in a position to provide heavy-launches. A number of smaller launch vehicles are lining-up for their maiden launches, from companies such as Skyrora (UK), Orbex (UK), Isar Aerospace (Germany).

One German company that has been the recipient of recent government support is Rocket Factory Augsburg, who have been given more funding through the ESA Boost! Programme (designed to support European launch startups). The funding is to support development of their vehicle, RFA One, at sites in Portugal, Germany and the UK. RFA One is a three-stage orbital vehicle, due to launch for the first time from Saxavord, Scotland, in April 2024.

Europe open launch sites, look to commercial cargo programme

Europe is set to become a hive of launch activity in the near future with launch sites opening-up across the UK (such as Saxavord), in Sweden and most recently, Norway. This week the Crown Prince of Norway opened what is billed as “the first operational orbital spaceport in Europe”, in Andøya. Germany’s Isar Aerospace will have exclusive access to the site for the launch of their two-stage Spectrum launch vehicle, but with no set launch date as of yet.

ESA aren’t only looking at building a commercialised model for launches, but this week also announced their intern to start a commercial cargo programme. The agency will begin a competition in order to source commercial vehicles to transport cargo to and from the ISS (and later newer stations), similar to the function of Sierra Space’s Dream Chaser, or the highly successful SpaceX Dragon Cargo.

It is still the early stages, but the ESA head said that “study contracts’ may be awarded to two or three companies at first, with the project later expanding under new funding arrangements from 2025.

Interestingly, this week Airbus have signed an agreement with Voyager Space (US) to explore the potential use of their Starlab commercial space station once the ISS is retired. The study will look into how the station can give Europe continued access to space, for crewed missions and scientific research. The station is currently expected to launch in 2028.

We are seeing Europe making a strong case for commercialisation, observing the roaring success in the US. Furthermore, considering ESA’s renewed energy and determination to “not miss the train” on the growing lunar economy, it seems that European space commercialisation may not end with only launch and orbital vehicles, but perhaps eventually extend to launder landing technology and resource utilisation.

Lunar surface to become hive of activity (Adobe)

Türkiye to the Moon and input sought on resource utilisation and mining

As well as ESA, Türkiye have become the latest nation to set their eyes on the Moon. As part of their Lunar Research Program the nation looks to send its own spacecraft by 2026.

In the first stage of the programme, known as AYAP-1 (Lunar Research Program Project 1), they will send a spacecraft to explore the Moon from orbit. In the second stage, named AYAP-2, will look to land a rover on the surface.

In 2021, president Erdoğan unveiled 10-year Turkish space programme, looking to make the nation compete on the world stage.

Australia will also stake their claim in future of lunar exploration, adding their SPIDER (Seismic Payload for Interplanetary Discovery, Exploration, and Research) as payload on Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost lander, due to head to the far side of the Moon in 2026.

SPIDER will be used to collect seismic data from the lunar surface, with data ultimately being used to understand the geology of the lunar subsurface and the presence of water. Furthermore, the mission is part of the Australian Space Agency’s “Moon to Mars initiative”, looking to use the Moon as a launchpad to Mars.

Moreover, we are again seeing an increasing interest in the future of the lunar economy, looking towards building an infrastructure for permanent habitation and resource extraction.

NASA and Canadian company look to mine lunar resources

Following this charge, NGen, Canada’s industry-led, non-profit organization leading Canada’s Global Innovation Cluster for Advanced Manufacturing, has launched its Moonshot 4 Mining, Minerals and Manufacturing (M4M3) initiative. The programme is aimed at supporting development of in-situ resource utilisation (ISRU) for both lunar and terrestrial applications.

Additionally, the M4M3 programme will build on the technology required to establish a permanent human presence on the Moon, building on Canada’s heritage in robotics, additive manufacturing and tech. NGen will receive financial support from the Canadian Space Agency and open calls for projects in the areas of mining, critical minerals and manufacturing.

NASA are also looking to support the development of ISRU technologies and on November 6th “issued a Request for Information (RFI) on Nov. 6 to formulate its future Lunar Infrastructure Foundational Technologies (LIFT-1) demonstration” (NASA). LIFT-1 is to demonstrate technologies capable of extracting oxygen from lunar soil, leading to eventual production and storage of oxygen on the Moon.

There is clear pattern emerging, which is that of established and new space nations now looking closer at the development of the lunar infrastructure. Türkiye and ESA maybe the latest to look towards the Moon, but we can expect more to come.

Share this article

10 November 2023

Europe Embraces US Commercial Space Strategy as Türkiye Sets Sights on Moon Mission - Space News Roundup

Illustration of Starlab's commercial station (Starlab/Voyager)

This week SpaceX launched their 80th mission of the year, already outnumbering their 2022 total of 61, signifying the astonishing success of the commercialisation of spaceflight. We are now beginning to see other players looking to replicate this success, such as the successful launch and landing of iSpace’s (China) Hyperbola-2Y single-stage last week. iSpace are using their vehicle to replicate the SpaceX workhorse, Falcon-9.

Sierra Space are also looking to ready themselves to enter the commercial space launch market with the completion of their Dream Chaser spaceplane. The vehicle, named Tenacity, is designed to ferry cargo to and from the ISS and will carry out its first launch maybe sometime next spring, using United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket.

Sierra are representative of just the latest piece of innovative spaceflight technology coming from the US commercial sector and represent the overall success of the model whereby national launches are now purchased rather than developed by national agencies.

As well as China looking to emulate this success, Europe appears to be finally getting on-board.

Europe switches to US model

Representatives from 22 European Space Agency nations came to an agreement this Monday to address the lack of independant European access to space, moving from a traditional, government-funded approach, to a commercial model, whereby ESA will look to buy services “as an anchor customer,” according to ESA head, Josef Aschbacher.

He went on to say that “I think it is fair to say today is a very successful day for space in Europe," but admitted that to will still take some time for the European launch market to mature and be in a position to provide heavy-launches. A number of smaller launch vehicles are lining-up for their maiden launches, from companies such as Skyrora (UK), Orbex (UK), Isar Aerospace (Germany).

One German company that has been the recipient of recent government support is Rocket Factory Augsburg, who have been given more funding through the ESA Boost! Programme (designed to support European launch startups). The funding is to support development of their vehicle, RFA One, at sites in Portugal, Germany and the UK. RFA One is a three-stage orbital vehicle, due to launch for the first time from Saxavord, Scotland, in April 2024.

Europe open launch sites, look to commercial cargo programme

Europe is set to become a hive of launch activity in the near future with launch sites opening-up across the UK (such as Saxavord), in Sweden and most recently, Norway. This week the Crown Prince of Norway opened what is billed as “the first operational orbital spaceport in Europe”, in Andøya. Germany’s Isar Aerospace will have exclusive access to the site for the launch of their two-stage Spectrum launch vehicle, but with no set launch date as of yet.

ESA aren’t only looking at building a commercialised model for launches, but this week also announced their intern to start a commercial cargo programme. The agency will begin a competition in order to source commercial vehicles to transport cargo to and from the ISS (and later newer stations), similar to the function of Sierra Space’s Dream Chaser, or the highly successful SpaceX Dragon Cargo.

It is still the early stages, but the ESA head said that “study contracts’ may be awarded to two or three companies at first, with the project later expanding under new funding arrangements from 2025.

Interestingly, this week Airbus have signed an agreement with Voyager Space (US) to explore the potential use of their Starlab commercial space station once the ISS is retired. The study will look into how the station can give Europe continued access to space, for crewed missions and scientific research. The station is currently expected to launch in 2028.

We are seeing Europe making a strong case for commercialisation, observing the roaring success in the US. Furthermore, considering ESA’s renewed energy and determination to “not miss the train” on the growing lunar economy, it seems that European space commercialisation may not end with only launch and orbital vehicles, but perhaps eventually extend to launder landing technology and resource utilisation.

Lunar surface to become hive of activity (Adobe)

Türkiye to the Moon and input sought on resource utilisation and mining

As well as ESA, Türkiye have become the latest nation to set their eyes on the Moon. As part of their Lunar Research Program the nation looks to send its own spacecraft by 2026.

In the first stage of the programme, known as AYAP-1 (Lunar Research Program Project 1), they will send a spacecraft to explore the Moon from orbit. In the second stage, named AYAP-2, will look to land a rover on the surface.

In 2021, president Erdoğan unveiled 10-year Turkish space programme, looking to make the nation compete on the world stage.

Australia will also stake their claim in future of lunar exploration, adding their SPIDER (Seismic Payload for Interplanetary Discovery, Exploration, and Research) as payload on Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost lander, due to head to the far side of the Moon in 2026.

SPIDER will be used to collect seismic data from the lunar surface, with data ultimately being used to understand the geology of the lunar subsurface and the presence of water. Furthermore, the mission is part of the Australian Space Agency’s “Moon to Mars initiative”, looking to use the Moon as a launchpad to Mars.

Moreover, we are again seeing an increasing interest in the future of the lunar economy, looking towards building an infrastructure for permanent habitation and resource extraction.

NASA and Canadian company look to mine lunar resources

Following this charge, NGen, Canada’s industry-led, non-profit organization leading Canada’s Global Innovation Cluster for Advanced Manufacturing, has launched its Moonshot 4 Mining, Minerals and Manufacturing (M4M3) initiative. The programme is aimed at supporting development of in-situ resource utilisation (ISRU) for both lunar and terrestrial applications.

Additionally, the M4M3 programme will build on the technology required to establish a permanent human presence on the Moon, building on Canada’s heritage in robotics, additive manufacturing and tech. NGen will receive financial support from the Canadian Space Agency and open calls for projects in the areas of mining, critical minerals and manufacturing.

NASA are also looking to support the development of ISRU technologies and on November 6th “issued a Request for Information (RFI) on Nov. 6 to formulate its future Lunar Infrastructure Foundational Technologies (LIFT-1) demonstration” (NASA). LIFT-1 is to demonstrate technologies capable of extracting oxygen from lunar soil, leading to eventual production and storage of oxygen on the Moon.

There is clear pattern emerging, which is that of established and new space nations now looking closer at the development of the lunar infrastructure. Türkiye and ESA maybe the latest to look towards the Moon, but we can expect more to come.

Share this article

External Links

This Week

*News articles posted here are not property of ANASDA GmbH and belong to their respected owners. Postings here are external links only.