13 December 2024

(Image: United Nations/DLR)

Last week, the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, in collaboration with Germany, Peru, and the United Arab Emirates, hosted the World Space Forum in Bonn, Germany. This year’s theme was ‘Sustainable Space for Sustainability on Earth’. The event brought together delegates and representatives from governments, agencies, industry, academia, and civil society, with over 90 nations represented.

The forum addressed critical issues affecting space and its role in achieving sustainability goals on Earth, as outlined in the Space 2030 Agenda. Discussions included the outcomes of the September UN Pact for the Future, the role of space in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (Space4SDGs), sustainable space activities, and the future of lunar exploration.

Bringing together diverse stakeholders, the forum aimed to strengthen partnerships, build dialogue, share best practices, and foster a common vision for addressing the challenges and maximising the benefits of space activities for both current and future generations.

Amidst the discussions and thought-provoking contributions, several key themes emerged. These included strategies for implementing Action 56 of the Pact for the Future, addressing the “three pillars” of space sustainability—debris management, space traffic management, and space resource utilisation—and exploring the benefits and approaches to effective information-sharing. Below, we delve deeper into each of these areas:

Implementing Action 56 Pact for the Future

On day one, panels revisited Action 56 of the Pact for the Future, which highlights the immense benefits and possibilities space offers humanity and our planet while emphasising the risks and challenges that must be effectively managed. Action 56 calls for strengthening international cooperation on space exploration and notably advocates for the inclusion of private sector and civil society participation, where applicable, in intergovernmental processes.

How non-state actors might contribute, for instance, at COPUOS or other intergovernmental platforms, remains an evolving discussion. However, we already see the inclusion of commercial and civil society participants at events such as the World Space Forum and the UN Conference on Sustainable Lunar Activities earlier this year.

Action 56 also reaffirms the necessity of upholding the Outer Space Treaty (OST) as the cornerstone of international space law. It emphasises the role of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) as the central forum for addressing the ongoing challenges of international cooperation and engagement in space governance.

”Three Pillars” - space traffic, space debris, space resources

Action 56 also highlights three key areas necessary for developing new frameworks: space traffic management (STM), space debris management, and space resource management.

Regarding STM, there is growing concern about the safety of operations, particularly in low Earth orbit (LEO), amid the increasing number of space objects and the rise of mega-constellations. Currently, there are over 10,000 active satellites in orbit, with SpaceX's Starlink accounting for more than half of these objects. Additionally, this week China began launching the first satellites for its 10,000+ satellite mega-constellation, Guowang, alongside plans for two other commercial Chinese constellations, G60 and Honghu. Amazon has also registered plans to launch a constellation of 3,000 satellites, named Kuiper.

Despite this, there are already principles in national and international law governing the activities of these actors. The Outer Space Treaty (OST) mandates that States bear responsibility for the actions of their non-state actors in space, ensuring that space activities are conducted with “due regard to the corresponding interests of all other States Parties to the Treaty.” Additionally, the Registration Convention requires States to register space objects with the UN, while the Liability Convention holds States responsible and liable for any damage caused by their registered space objects.

However, concerns were raised at the Forum about the need for more mechanisms to prevent collisions in an increasingly congested Earth orbit. This could include addressing even seemingly simple tasks, such as ensuring clear points of contact and maintaining a shared “space phonebook” to facilitate urgent coordination when manoeuvring around other space objects.

Information-sharing

All these issues share a common thread: the need for information sharing to maintain safety and transparency in operations. This is not an easy challenge to address, especially in an era of increasing competition, the growing value placed on finite space resources, and the dual-use nature of space technology for defence.

There are provisions in place to support information sharing, such as the Registration Convention and Article XI of the Outer Space Treaty (OST), which was widely discussed at the Forum. This article was also highlighted at the UN Conference on Space Law and Policy, as well as at this year’s COPUOS meeting, where it was presented as a means to encourage more information sharing. Article XI itself calls on States to submit details to the UN Secretary-General about the nature, conduct, and locations of their space activities.

The challenge, however, lies in determining what details should be shared and how willing governments and commercial actors will be to share information, especially concerning increasingly contentious issues like sourcing and utilising valuable space resources. While utilising Article XI could be a suitable approach, overcoming geopolitical tensions, particularly between the US and China, will be a significant obstacle. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson has stated that the US is ‘in a race’ with China, and discussions in the US Congress last year included calls to secure lunar resources ahead of China. Some even proposed using the concept of “due regard” in the OST to create exclusion zones (applied within the Artemis Accords) on the Moon, not only to prevent harmful interference with other activities but also to secure mineral resources within those zones. Competition, mistrust, and geopolitical dynamics will present difficult hurdles to overcome.

(Image: NASA)

Lunar resource protecting missions, NASA delay Artemis again

International law, regulation, and transparency of lunar activities urgently needs to be addressed as we witness a growing cadence of lunar missions and the prospect of both state and commercially-driven lunar resource activities in the future. Natural resources, such as water, are vital for supporting a sustained lunar presence and for extending humanity's reach into deep space.

Commercial actors are positioning themselves to take the lead in extracting these resources. For instance, Starpath Robotics (US) is developing mining rovers and an in-situ refinery system. Another US startup, Interlune, is working on extracting and retrieving helium-3 from the Moon for use on Earth. This isotope, extremely rare on Earth, is claimed by Interlune to be commercially viable for medical imaging, quantum computing, and, most excitingly, future nuclear fusion reactors.

This week, lunar exploration company iSpace signed a memorandum of understanding with lunar mining company Magna Petra to utilise commercial quantities of helium-3 for use on Earth. Magna Petra claims that they will use non-destructive extraction techniques, scraping only the top few centimetres of lunar regolith. However, while the company suggests there could be around 25 million tons of helium-3 on the Moon, some experts argue that the actual quantity may be far less.

Despite the uncertainty, interest and commercial innovation in lunar resource extraction continues to grow. This week, Australia’s Fleet Space Technologies raised $100 million to develop remote, satellite-based mineral prospecting technology, which will also be used on the Moon. The company plans to send versions of their sensor to the Moon with Firefly Aerospace (US) in 2026.

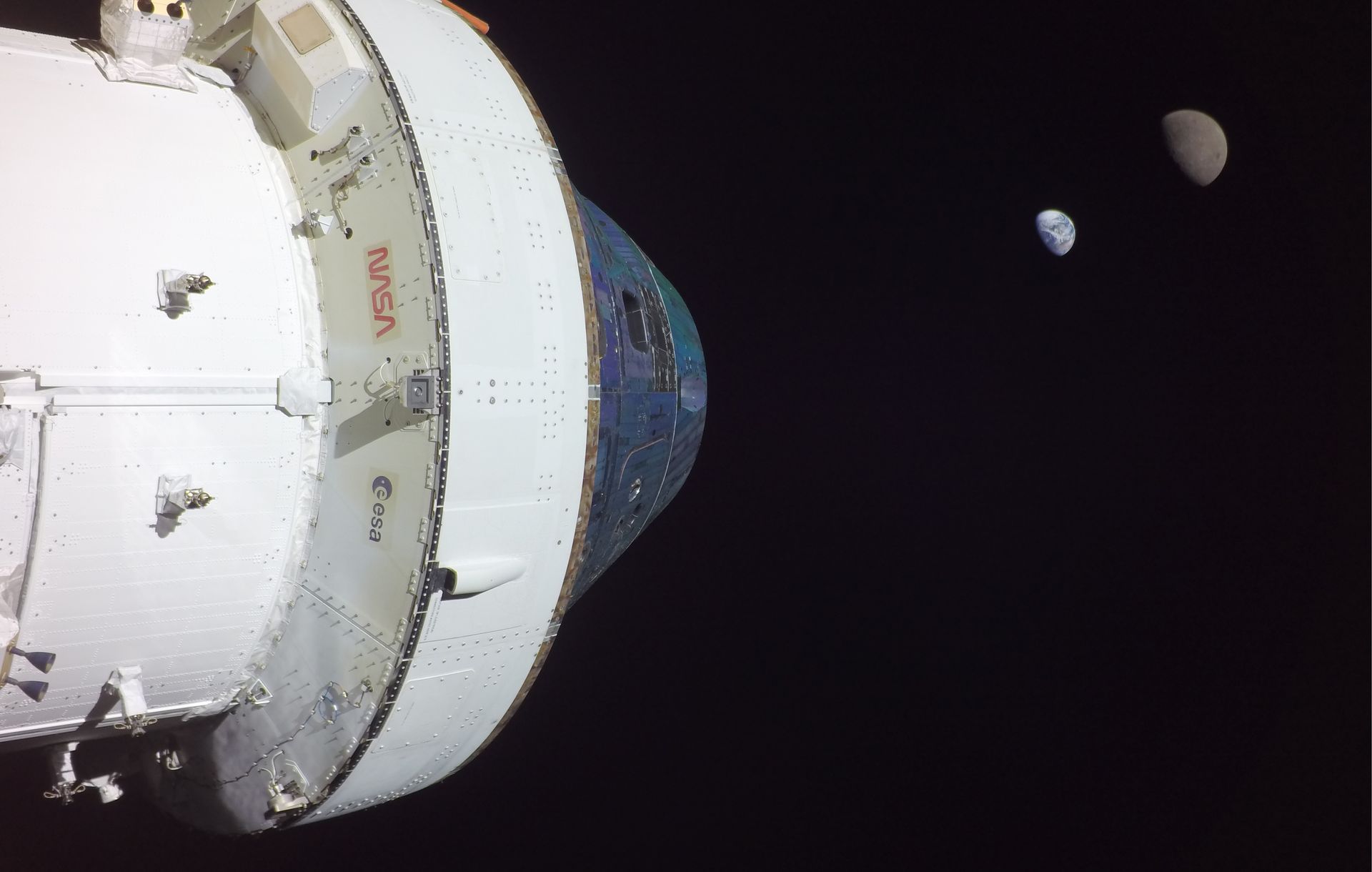

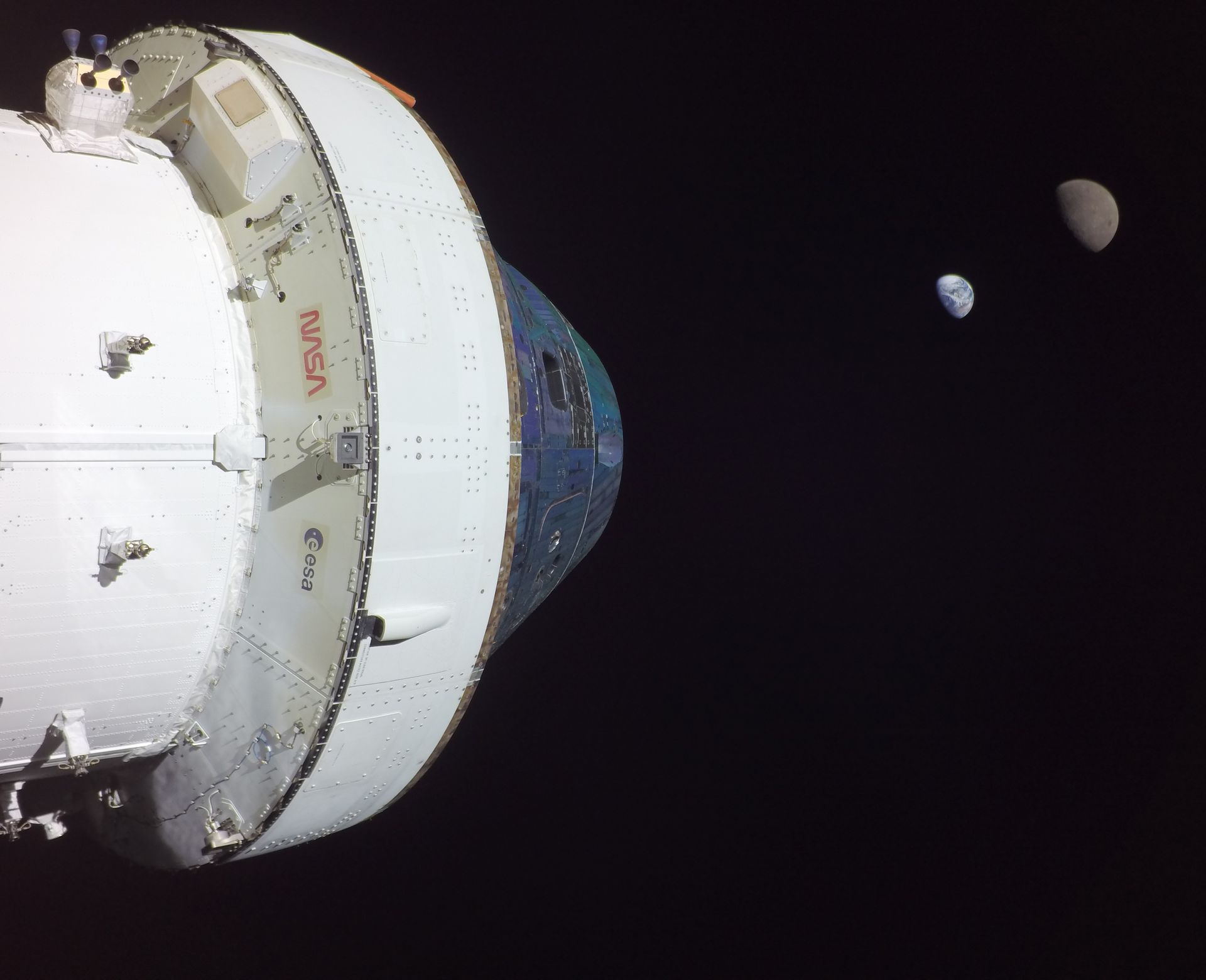

Artemis I Orion vehicle looking on Earth and the Moon (Image: NASA)

Geopolitical tensions and amidst intensifying lunar race

Tensions between the US and China remain high, and this week, the rivalry took another step forward as the race to return humans to the Moon intensified. NASA again delayed its Artemis 2 and 3 missions, with the latter now scheduled to transport astronauts to the Moon no sooner than mid-2027. While the delay was anticipated, NASA finds itself in a closely contested race with China, which aims to deliver taikonauts to the Moon by 2030.

Moreover, both countries expanded their lunar ‘alliances’ this week. Panama and Austria signed the US-led Artemis Accords (now numbering 50 signatories), a non-binding framework for the use of outer space, while Oman-based satellite company Oman Lens joined China's International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project.

Both frameworks represent progressive developments, aiming to bring nations to a common regulatory ground. The Artemis Accords have published norms and principles that include provisions for lunar and space mining, as well as calls for partnerships with the commercial sector. However, while China does not have a publicly available set of soft law regulations for their ILRS project, a paper submitted to the working group on the legal aspects of space resource activities expressed concerns about the depletion of lunar resources and the potential negative impact of commercial space resource activities.

In orbit and looking toward the Moon, it will be vital to continue discussions and implement the Pact for the Future as a means of steering away from conflict, enhancing safety, and ensuring that the benefits of space are shared equitably.

(Image Render: Blue Origin)

13 December 2024

Advancing the Pact for the Future, Enhancing Space Traffic Management, Information Sharing, and Space Resource Utilisation - World Space Forum

Last week, the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, in collaboration with Germany, Peru, and the United Arab Emirates, hosted the World Space Forum in Bonn, Germany. This year’s theme was ‘Sustainable Space for Sustainability on Earth’. The event brought together delegates and representatives from governments, agencies, industry, academia, and civil society, with over 90 nations represented.

The forum addressed critical issues affecting space and its role in achieving sustainability goals on Earth, as outlined in the Space 2030 Agenda. Discussions included the outcomes of the September UN Pact for the Future, the role of space in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (Space4SDGs), sustainable space activities, and the future of lunar exploration.

Bringing together diverse stakeholders, the forum aimed to strengthen partnerships, build dialogue, share best practices, and foster a common vision for addressing the challenges and maximising the benefits of space activities for both current and future generations.

Amidst the discussions and thought-provoking contributions, several key themes emerged. These included strategies for implementing Action 56 of the Pact for the Future, addressing the “three pillars” of space sustainability—debris management, space traffic management, and space resource utilisation—and exploring the benefits and approaches to effective information-sharing. Below, we delve deeper into each of these areas:

Implementing Action 56 Pact for the Future

On day one, panels revisited Action 56 of the Pact for the Future, which highlights the immense benefits and possibilities space offers humanity and our planet while emphasising the risks and challenges that must be effectively managed. Action 56 calls for strengthening international cooperation on space exploration and notably advocates for the inclusion of private sector and civil society participation, where applicable, in intergovernmental processes.

How non-state actors might contribute, for instance, at COPUOS or other intergovernmental platforms, remains an evolving discussion. However, we already see the inclusion of commercial and civil society participants at events such as the World Space Forum and the UN Conference on Sustainable Lunar Activities earlier this year.

Action 56 also reaffirms the necessity of upholding the Outer Space Treaty (OST) as the cornerstone of international space law. It emphasises the role of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) as the central forum for addressing the ongoing challenges of international cooperation and engagement in space governance.

”Three Pillars” - space traffic, space debris, space resources

Action 56 also highlights three key areas necessary for developing new frameworks: space traffic management (STM), space debris management, and space resource management.

Regarding STM, there is growing concern about the safety of operations, particularly in low Earth orbit (LEO), amid the increasing number of space objects and the rise of mega-constellations. Currently, there are over 10,000 active satellites in orbit, with SpaceX's Starlink accounting for more than half of these objects. Additionally, this week China began launching the first satellites for its 10,000+ satellite mega-constellation, Guowang, alongside plans for two other commercial Chinese constellations, G60 and Honghu. Amazon has also registered plans to launch a constellation of 3,000 satellites, named Kuiper.

Despite this, there are already principles in national and international law governing the activities of these actors. The Outer Space Treaty (OST) mandates that States bear responsibility for the actions of their non-state actors in space, ensuring that space activities are conducted with “due regard to the corresponding interests of all other States Parties to the Treaty.” Additionally, the Registration Convention requires States to register space objects with the UN, while the Liability Convention holds States responsible and liable for any damage caused by their registered space objects.

However, concerns were raised at the Forum about the need for more mechanisms to prevent collisions in an increasingly congested Earth orbit. This could include addressing even seemingly simple tasks, such as ensuring clear points of contact and maintaining a shared “space phonebook” to facilitate urgent coordination when manoeuvring around other space objects.

Information-sharing

All these issues share a common thread: the need for information sharing to maintain safety and transparency in operations. This is not an easy challenge to address, especially in an era of increasing competition, the growing value placed on finite space resources, and the dual-use nature of space technology for defence.

There are provisions in place to support information sharing, such as the Registration Convention and Article XI of the Outer Space Treaty (OST), which was widely discussed at the Forum. This article was also highlighted at the UN Conference on Space Law and Policy, as well as at this year’s COPUOS meeting, where it was presented as a means to encourage more information sharing. Article XI itself calls on States to submit details to the UN Secretary-General about the nature, conduct, and locations of their space activities.

The challenge, however, lies in determining what details should be shared and how willing governments and commercial actors will be to share information, especially concerning increasingly contentious issues like sourcing and utilising valuable space resources. While utilising Article XI could be a suitable approach, overcoming geopolitical tensions, particularly between the US and China, will be a significant obstacle. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson has stated that the US is ‘in a race’ with China, and discussions in the US Congress last year included calls to secure lunar resources ahead of China. Some even proposed using the concept of “due regard” in the OST to create exclusion zones (applied within the Artemis Accords) on the Moon, not only to prevent harmful interference with other activities but also to secure mineral resources within those zones. Competition, mistrust, and geopolitical dynamics will present difficult hurdles to overcome.

Lunar resource protecting missions, NASA delay Artemis again

International law, regulation, and transparency of lunar activities urgently needs to be addressed as we witness a growing cadence of lunar missions and the prospect of both state and commercially-driven lunar resource activities in the future. Natural resources, such as water, are vital for supporting a sustained lunar presence and for extending humanity's reach into deep space.

Commercial actors are positioning themselves to take the lead in extracting these resources. For instance, Starpath Robotics (US) is developing mining rovers and an in-situ refinery system. Another US startup, Interlune, is working on extracting and retrieving helium-3 from the Moon for use on Earth. This isotope, extremely rare on Earth, is claimed by Interlune to be commercially viable for medical imaging, quantum computing, and, most excitingly, future nuclear fusion reactors.

This week, lunar exploration company iSpace signed a memorandum of understanding with lunar mining company Magna Petra to utilise commercial quantities of helium-3 for use on Earth. Magna Petra claims that they will use non-destructive extraction techniques, scraping only the top few centimetres of lunar regolith. However, while the company suggests there could be around 25 million tons of helium-3 on the Moon, some experts argue that the actual quantity may be far less.

Despite the uncertainty, interest and commercial innovation in lunar resource extraction continues to grow. This week, Australia’s Fleet Space Technologies raised $100 million to develop remote, satellite-based mineral prospecting technology, which will also be used on the Moon. The company plans to send versions of their sensor to the Moon with Firefly Aerospace (US) in 2026.

Geopolitical tensions and amidst intensifying lunar race

Tensions between the US and China remain high, and this week, the rivalry took another step forward as the race to return humans to the Moon intensified. NASA again delayed its Artemis 2 and 3 missions, with the latter now scheduled to transport astronauts to the Moon no sooner than mid-2027. While the delay was anticipated, NASA finds itself in a closely contested race with China, which aims to deliver taikonauts to the Moon by 2030.

Moreover, both countries expanded their lunar ‘alliances’ this week. Panama and Austria signed the US-led Artemis Accords (now numbering 50 signatories), a non-binding framework for the use of outer space, while Oman-based satellite company Oman Lens joined China's International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project.

Both frameworks represent progressive developments, aiming to bring nations to a common regulatory ground. The Artemis Accords have published norms and principles that include provisions for lunar and space mining, as well as calls for partnerships with the commercial sector. However, while China does not have a publicly available set of soft law regulations for their ILRS project, a paper submitted to the working group on the legal aspects of space resource activities expressed concerns about the depletion of lunar resources and the potential negative impact of commercial space resource activities.

In orbit and looking toward the Moon, it will be vital to continue discussions and implement the Pact for the Future as a means of steering away from conflict, enhancing safety, and ensuring that the benefits of space are shared equitably.

Share this article

13 December 2024

Advancing the Pact for the Future, Enhancing Space Traffic Management, Information Sharing, and Space Resource Utilisation - World Space Forum Special

(Image: United Nations/DLR)

Last week, the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, in collaboration with Germany, Peru, and the United Arab Emirates, hosted the World Space Forum in Bonn, Germany. This year’s theme was ‘Sustainable Space for Sustainability on Earth’. The event brought together delegates and representatives from governments, agencies, industry, academia, and civil society, with over 90 nations represented.

The forum addressed critical issues affecting space and its role in achieving sustainability goals on Earth, as outlined in the Space 2030 Agenda. Discussions included the outcomes of the September UN Pact for the Future, the role of space in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (Space4SDGs), sustainable space activities, and the future of lunar exploration.

Bringing together diverse stakeholders, the forum aimed to strengthen partnerships, build dialogue, share best practices, and foster a common vision for addressing the challenges and maximising the benefits of space activities for both current and future generations.

Amidst the discussions and thought-provoking contributions, several key themes emerged. These included strategies for implementing Action 56 of the Pact for the Future, addressing the “three pillars” of space sustainability—debris management, space traffic management, and space resource utilisation—and exploring the benefits and approaches to effective information-sharing. Below, we delve deeper into each of these areas:

Implementing Action 56 Pact for the Future

On day one, panels revisited Action 56 of the Pact for the Future, which highlights the immense benefits and possibilities space offers humanity and our planet while emphasising the risks and challenges that must be effectively managed. Action 56 calls for strengthening international cooperation on space exploration and notably advocates for the inclusion of private sector and civil society participation, where applicable, in intergovernmental processes.

How non-state actors might contribute, for instance, at COPUOS or other intergovernmental platforms, remains an evolving discussion. However, we already see the inclusion of commercial and civil society participants at events such as the World Space Forum and the UN Conference on Sustainable Lunar Activities earlier this year.

Action 56 also reaffirms the necessity of upholding the Outer Space Treaty (OST) as the cornerstone of international space law. It emphasises the role of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) as the central forum for addressing the ongoing challenges of international cooperation and engagement in space governance.

”Three Pillars” - space traffic, space debris, space resources

Action 56 also highlights three key areas necessary for developing new frameworks: space traffic management (STM), space debris management, and space resource management.

Regarding STM, there is growing concern about the safety of operations, particularly in low Earth orbit (LEO), amid the increasing number of space objects and the rise of mega-constellations. Currently, there are over 10,000 active satellites in orbit, with SpaceX's Starlink accounting for more than half of these objects. Additionally, this week China began launching the first satellites for its 10,000+ satellite mega-constellation, Guowang, alongside plans for two other commercial Chinese constellations, G60 and Honghu. Amazon has also registered plans to launch a constellation of 3,000 satellites, named Kuiper.

Despite this, there are already principles in national and international law governing the activities of these actors. The Outer Space Treaty (OST) mandates that States bear responsibility for the actions of their non-state actors in space, ensuring that space activities are conducted with “due regard to the corresponding interests of all other States Parties to the Treaty.” Additionally, the Registration Convention requires States to register space objects with the UN, while the Liability Convention holds States responsible and liable for any damage caused by their registered space objects.

However, concerns were raised at the Forum about the need for more mechanisms to prevent collisions in an increasingly congested Earth orbit. This could include addressing even seemingly simple tasks, such as ensuring clear points of contact and maintaining a shared “space phonebook” to facilitate urgent coordination when manoeuvring around other space objects.

Information-sharing

All these issues share a common thread: the need for information sharing to maintain safety and transparency in operations. This is not an easy challenge to address, especially in an era of increasing competition, the growing value placed on finite space resources, and the dual-use nature of space technology for defence.

There are provisions in place to support information sharing, such as the Registration Convention and Article XI of the Outer Space Treaty (OST), which was widely discussed at the Forum. This article was also highlighted at the UN Conference on Space Law and Policy, as well as at this year’s COPUOS meeting, where it was presented as a means to encourage more information sharing. Article XI itself calls on States to submit details to the UN Secretary-General about the nature, conduct, and locations of their space activities.

The challenge, however, lies in determining what details should be shared and how willing governments and commercial actors will be to share information, especially concerning increasingly contentious issues like sourcing and utilising valuable space resources. While utilising Article XI could be a suitable approach, overcoming geopolitical tensions, particularly between the US and China, will be a significant obstacle. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson has stated that the US is ‘in a race’ with China, and discussions in the US Congress last year included calls to secure lunar resources ahead of China. Some even proposed using the concept of “due regard” in the OST to create exclusion zones (applied within the Artemis Accords) on the Moon, not only to prevent harmful interference with other activities but also to secure mineral resources within those zones. Competition, mistrust, and geopolitical dynamics will present difficult hurdles to overcome.

(Image: NASA)

Lunar resource protecting missions, NASA delay Artemis again

International law, regulation, and transparency of lunar activities urgently needs to be addressed as we witness a growing cadence of lunar missions and the prospect of both state and commercially-driven lunar resource activities in the future. Natural resources, such as water, are vital for supporting a sustained lunar presence and for extending humanity's reach into deep space.

Commercial actors are positioning themselves to take the lead in extracting these resources. For instance, Starpath Robotics (US) is developing mining rovers and an in-situ refinery system. Another US startup, Interlune, is working on extracting and retrieving helium-3 from the Moon for use on Earth. This isotope, extremely rare on Earth, is claimed by Interlune to be commercially viable for medical imaging, quantum computing, and, most excitingly, future nuclear fusion reactors.

This week, lunar exploration company iSpace signed a memorandum of understanding with lunar mining company Magna Petra to utilise commercial quantities of helium-3 for use on Earth. Magna Petra claims that they will use non-destructive extraction techniques, scraping only the top few centimetres of lunar regolith. However, while the company suggests there could be around 25 million tons of helium-3 on the Moon, some experts argue that the actual quantity may be far less.

Despite the uncertainty, interest and commercial innovation in lunar resource extraction continues to grow. This week, Australia’s Fleet Space Technologies raised $100 million to develop remote, satellite-based mineral prospecting technology, which will also be used on the Moon. The company plans to send versions of their sensor to the Moon with Firefly Aerospace (US) in 2026.

Artemis I Orion vehicle looking on Earth and the Moon (Image: NASA)

Geopolitical tensions and amidst intensifying lunar race

Tensions between the US and China remain high, and this week, the rivalry took another step forward as the race to return humans to the Moon intensified. NASA again delayed its Artemis 2 and 3 missions, with the latter now scheduled to transport astronauts to the Moon no sooner than mid-2027. While the delay was anticipated, NASA finds itself in a closely contested race with China, which aims to deliver taikonauts to the Moon by 2030.

Moreover, both countries expanded their lunar ‘alliances’ this week. Panama and Austria signed the US-led Artemis Accords (now numbering 50 signatories), a non-binding framework for the use of outer space, while Oman-based satellite company Oman Lens joined China's International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project.

Both frameworks represent progressive developments, aiming to bring nations to a common regulatory ground. The Artemis Accords have published norms and principles that include provisions for lunar and space mining, as well as calls for partnerships with the commercial sector. However, while China does not have a publicly available set of soft law regulations for their ILRS project, a paper submitted to the working group on the legal aspects of space resource activities expressed concerns about the depletion of lunar resources and the potential negative impact of commercial space resource activities.

In orbit and looking toward the Moon, it will be vital to continue discussions and implement the Pact for the Future as a means of steering away from conflict, enhancing safety, and ensuring that the benefits of space are shared equitably.

Share this article